Go Up to Fundamental Syntactic Elements Index

This topic describes syntax rules of forming Delphi expressions.

The following items are covered in this topic:

- Valid Delphi Expressions

- Operators

- Function calls

- Set constructors

- Indexes

- Typecasts

Contents

- 1 Expressions

- 2 Operators

- 2.1 Arithmetic Operators

- 2.2 Boolean Operators

- 2.3 Complete Versus Short-Circuit Boolean Evaluation

- 2.4 Logical (Bitwise) Operators

- 2.4.1 Example

- 2.5 String Operators

- 2.6 Pointer Operators

- 2.7 Set Operators

- 2.8 Relational Operators

- 2.9 Class and Interface Operators

- 2.10 The @ Operator

- 2.11 Operator Precedence

- 3 Function Calls

- 4 Set Constructors

- 5 Indexes

- 6 Typecasts

- 6.1 Value Typecasts

- 6.2 Variable Typecasts

- 7 See Also

Expressions

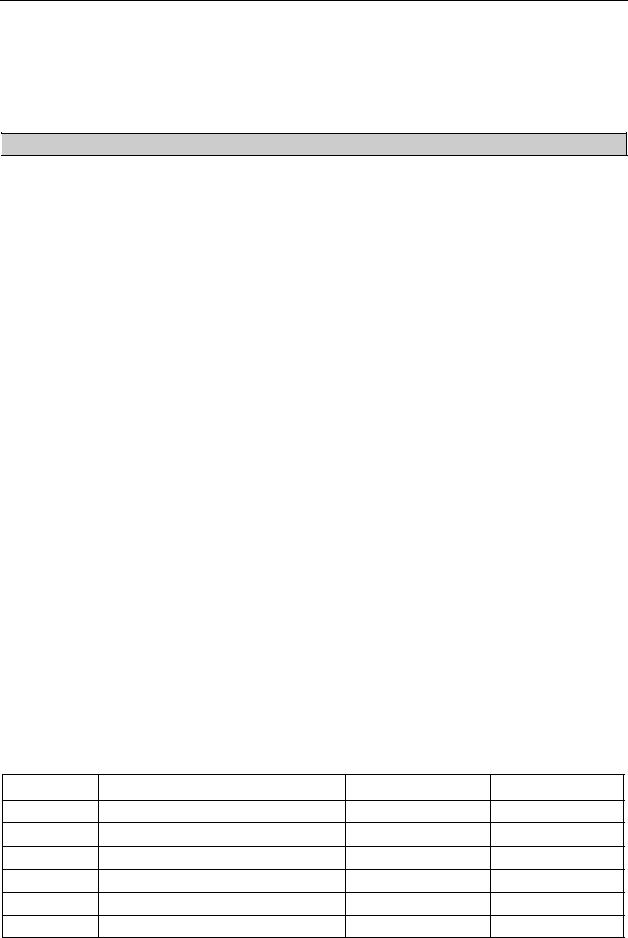

An expression is a construction that returns a value. The following table shows examples of Delphi expressions:

|

|

variable |

|

|

address of the variable X |

|

|

integer constant |

|

|

variable |

|

|

function call |

|

|

product of X and Y |

|

|

quotient of Z and (1 — Z) |

|

|

Boolean |

|

|

Boolean |

|

|

negation of a Boolean |

|

|

set |

|

|

value typecast |

The simplest expressions are variables and constants (described in About Data Types (Delphi)). More complex expressions are built from simpler ones using operators, function calls, set constructors, indexes, and typecasts.

Operators

Operators behave like predefined functions that are part of the Delphi language. For example, the expression (X + Y) is built from the variables X and Y, called operands, with the + operator; when X and Y represent integers or reals, (X + Y) returns their sum. Operators include @, not, ^, *, /, div, mod, and, shl, shr, as, +, —, or, xor, =, >, <, <>, <=, >=, in, and is.

The operators @, not, and ^ are unary (taking one operand). All other operators are binary (taking two operands), except that + and — can function as either a unary or binary operator. A unary operator always precedes its operand (for example, -B), except for ^, which follows its operand (for example, P^). A binary operator is placed between its operands (for example, A = 7).

Some operators behave differently depending on the type of data passed to them. For example, not performs bitwise negation on an integer operand and logical negation on a Boolean operand. Such operators appear below under multiple categories.

Except for ^, is, and in, all operators can take operands of type Variant; for details, see Variant Types (Delphi).

The sections that follow assume some familiarity with Delphi data types; for more information, see About Data Types (Delphi).

For information about operator precedence in complex expressions, see Operator Precedence Rules, later in this topic.

Arithmetic Operators

Arithmetic operators, which take real or integer operands, include +, —, *, /, div, and mod.

Binary Arithmetic Operators:

| Operator | Operation | Operand Types | Result Type | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

+ |

addition |

integer, real |

integer, real |

|

|

— |

subtraction |

integer, real |

integer, real |

|

|

* |

multiplication |

integer, real |

integer, real |

|

|

/ |

real division |

integer, real |

real |

|

|

div |

integer division |

integer |

integer |

|

|

mod |

remainder |

integer |

integer |

|

Unary arithmetic operators:

| Operator | Operation | Operand Type | Result Type | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

+ |

sign identity |

integer, real |

integer, real |

|

|

— |

sign negation |

integer, real |

integer, real |

|

The following rules apply to arithmetic operators:

- The value of

x / yis of type Extended, regardless of the types ofxandy. For other arithmetic operators, the result is of type Extended whenever at least one operand is a real; otherwise, the result is of type Int64 when at least one operand is of type Int64; otherwise, the result is of type Integer. If an operand’s type is a subrange of an integer type, it is treated as if it were of the integer type. - The value of

x div yis the value ofx / yrounded in the direction of zero to the nearest integer. - The mod operator returns the remainder obtained by dividing its operands. In other words,

x mod y = x - (x div y) * y. - A run-time error occurs when

yis zero in an expression of the formx / y,x div y, orx mod y.

Boolean Operators

The Boolean operators not, and, or, and xor take operands of any Boolean type and return a value of type Boolean.

Boolean Operators:

| Operator | Operation | Operand Types | Result Type | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

not |

negation |

Boolean |

Boolean |

|

|

and |

conjunction |

Boolean |

Boolean |

|

|

or |

disjunction |

Boolean |

Boolean |

|

|

xor |

exclusive disjunction |

Boolean |

Boolean |

|

These operations are governed by standard rules of Boolean logic. For example, an expression of the form x and y is True if and only if both x and y are True.

Complete Versus Short-Circuit Boolean Evaluation

The compiler supports two modes of evaluation for the and and or operators: complete evaluation and short-circuit (partial) evaluation. Complete evaluation means that each conjunct or disjunct is evaluated, even when the result of the entire expression is already determined. Short-circuit evaluation means strict left-to-right evaluation that stops as soon as the result of the entire expression is determined. For example, if the expression A and B is evaluated under short-circuit mode when A is False, the compiler will not evaluate B; it knows that the entire expression is False as soon as it evaluates A.

Short-circuit evaluation is usually preferable because it guarantees minimum execution time and, in most cases, minimum code size. Complete evaluation is sometimes convenient when one operand is a function with side effects that alter the execution of the program.

Short-circuit evaluation also allows the use of constructions that might otherwise result in illegal run-time operations. For example, the following code iterates through the string S, up to the first comma.

while (I <= Length(S)) and (S[I] <> ',') do begin ... Inc(I); end;

In the case where S has no commas, the last iteration increments I to a value which is greater than the length of S. When the while condition is next tested, complete evaluation results in an attempt to read S[I], which could cause a run-time error. Under short-circuit evaluation, in contrast, the second part of the while condition (S[I] <> ',') is not evaluated after the first part fails.

Use the $B compiler directive to control evaluation mode. The default state is {$B}, which enables short-circuit evaluation. To enable complete evaluation locally, add the {$B+} directive to your code. You can also switch to complete evaluation on a project-wide basis by selecting Complete Boolean Evaluation in the Compiler Options dialog (all source units will need to be recompiled).

Note: If either operand involves a variant, the compiler always performs complete evaluation (even in the

{$B}state).

Logical (Bitwise) Operators

The following logical operators perform bitwise manipulation on integer operands. For example, if the value stored in X (in binary) is 001101 and the value stored in Y is 100001, the statement:

Z := X or Y;

assigns the value 101101 to Z.

Logical (Bitwise) Operators:

| Operator | Operation | Operand Types | Result Type | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

not |

bitwise negation |

integer |

integer |

|

|

and |

bitwise and |

integer |

integer |

|

|

or |

bitwise or |

integer |

integer |

|

|

xor |

bitwise xor |

integer |

integer |

|

|

shl |

bitwise shift left |

integer |

integer |

|

|

shr |

bitwise shift right |

integer |

integer |

|

The following rules apply to bitwise operators:

- The result of a not operation is of the same type as the operand.

- If the operands of an and, or, or xor operation are both integers, the result is of the predefined integer type with the smallest range that includes all possible values of both types.

- The operations

x shl yandx shr yshift the value ofxto the left or right byybits, which (ifxis an unsigned integer) is equivalent to multiplying or dividingxby2^y; the result is of the same type asx. For example, ifNstores the value01101(decimal 13), thenN shl 1returns11010(decimal 26). Note that the value ofyis interpreted modulo the size of the type ofx. Thus for example, ifxis an integer,x shl 40is interpreted asx shl 8because an integer is 32 bits and 40 mod 32 is 8.

Example

If x is a negative integer, the shl and shr operations are made clear in the following example:

var x: integer; y: string; ... begin x := -20; x := x shr 1; //As the number is shifted to the right by 1 bit, the sign bit's value replaced is with 0 (all negative numbers have the sign bit set to 1). y := IntToHex(x, 8); writeln(y); //Therefore, x is positive. //Decimal value: 2147483638 //Hexadecimal value: 7FFFFFF6 //Binary value: 0111 1111 1111 1111 1111 1111 1111 0110 end.

String Operators

The relational operators =, <>, <, >, <=, and >= all take string operands (see Relational operators later in this section). The + operator concatenates two strings.

String Operators:

| Operator | Operation | Operand Types | Result Type | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

+ |

concatenation |

string, packed string, character |

string |

|

The following rules apply to string concatenation:

- The operands for + can be strings, packed strings (packed arrays of type Char), or characters. However, if one operand is of type WideChar, the other operand must be a long string (UnicodeString, AnsiString, or WideString).

- The result of a + operation is compatible with any string type. However, if the operands are both short strings or characters, and their combined length is greater than 255, the result is truncated to the first 255 characters.

Pointer Operators

- The relational operators <, >, <=, and >= can take operands of type PAnsiChar and PWideChar (see Relational operators). The following operators also take pointers as operands. For more information about pointers, see Pointers and Pointer Types (Delphi) in About Data Types (Delphi).

Character-pointer operators:

| Operator | Operation | Operand Types | Result Type | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

+ |

pointer addition |

character pointer, integer |

character pointer |

|

|

— |

pointer subtraction |

character pointer, integer |

character pointer, integer |

|

|

^ |

pointer dereference |

pointer |

base type of pointer |

|

|

= |

equality |

pointer |

Boolean |

|

|

<> |

inequality |

pointer |

Boolean |

|

The ^ operator dereferences a pointer. Its operand can be a pointer of any type except the generic Pointer, which must be typecast before dereferencing.

P = Q is True just in case P and Q point to the same address; otherwise, P <> Q is True.

You can use the + and — operators to increment and decrement the offset of a character pointer. You can also use — to calculate the difference between the offsets of two character pointers. The following rules apply:

- If

Iis an integer andPis a character pointer, thenP + IaddsIto the address given byP; that is, it returns a pointer to the addressIcharacters afterP. (The expressionI + Pis equivalent toP + I.)P - IsubtractsIfrom the address given byP; that is, it returns a pointer to the addressIcharacters beforeP. This is true for PAnsiChar pointers; for PWideChar pointersP + IaddsI * SizeOf(WideChar)toP. - If

PandQare both character pointers, thenP - Qcomputes the difference between the address given byP(the higher address) and the address given byQ(the lower address); that is, it returns an integer denoting the number of characters betweenPandQ.

P + Qis not defined.

Set Operators

The following operators take sets as operands.

Set Operators:

| Operator | Operation | Operand Types | Result Type | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

+ |

union |

set |

set |

|

|

— |

difference |

set |

set |

|

|

* |

intersection |

set |

set |

|

|

<= |

subset |

set |

Boolean |

|

|

>= |

superset |

set |

Boolean |

|

|

= |

equality |

set |

Boolean |

|

|

<> |

inequality |

set |

Boolean |

|

|

in |

membership |

ordinal, set |

Boolean |

|

The following rules apply to +, —, and *:

- An ordinal

Ois inX + Yif and only ifOis inXorY(or both).Ois inX - Yif and only ifOis inXbut not inY.Ois inX * Yif and only ifOis in bothXandY. - The result of a +, —, or * operation is of the type

set of A..B, whereAis the smallest ordinal value in the result set andBis the largest.

The following rules apply to <=, >=, =, <>, and in:

X <= Yis True just in case every member ofXis a member ofY;Z >= Wis equivalent toW <= Z.U = Vis True just in caseUandVcontain exactly the same members; otherwise,U <> Vis True.- For an ordinal

Oand a setS,O in Sis True just in caseOis a member ofS.

Relational Operators

Relational operators are used to compare two operands. The operators =, <>, <=, and >= also apply to sets.

Relational Operators:

| Operator | Operation | Operand Types | Result Type | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

= |

equality |

simple, class, class reference, interface, string, packed string |

Boolean |

|

|

<> |

inequality |

simple, class, class reference, interface, string, packed string |

Boolean |

|

|

< |

less-than |

simple, string, packed string, PChar |

Boolean |

|

|

> |

greater-than |

simple, string, packed string, PChar |

Boolean |

|

|

<= |

less-than-or-equal-to |

simple, string, packed string, PChar |

Boolean |

|

|

>= |

greater-than-or-equal-to |

simple, string, packed string, PChar |

Boolean |

|

For most simple types, comparison is straightforward. For example, I = J is True just in case I and J have the same value, and I <> J is True otherwise. The following rules apply to relational operators.

- Operands must be of compatible types, except that a real and an integer can be compared.

- Strings are compared according to the ordinal values that make up the characters that make up the string. Character types are treated as strings of length 1.

- Two packed strings must have the same number of components to be compared. When a packed string with

ncomponents is compared to a string, the packed string is treated as a string of lengthn. - Use the operators <, >, <=, and >= to compare PAnsiChar (and PWideChar) operands only if the two pointers point within the same character array.

- The operators = and <> can take operands of class and class-reference types. With operands of a class type, = and <> are evaluated according the rules that apply to pointers:

C = Dis True just in caseCandDpoint to the same instance object, andC <> Dis True otherwise. With operands of a class-reference type,C = Dis True just in caseCandDdenote the same class, andC <> Dis True otherwise. This does not compare the data stored in the classes. For more information about classes, see Classes and Objects (Delphi).

Class and Interface Operators

The operators as and is take classes and instance objects as operands; as operates on interfaces as well. For more information, see Classes and Objects (Delphi), Object Interfaces (Delphi) and Interface References (Delphi).

The relational operators = and <> also operate on classes.

The @ Operator

The @ operator returns the address of a variable, or of a function, procedure, or method; that is, @ constructs a pointer to its operand. For more information about pointers, see «Pointers and Pointer Types» in About Data Types (Delphi). The following rules apply to @.

- If

Xis a variable,@Xreturns the address ofX. (Special rules apply whenXis a procedural variable; see «Procedural Types in Statements and Expressions» in About Data Types (Delphi).) The type of@Xis Pointer if the default{$T}compiler directive is in effect. In the{$T+}state,@Xis of type^T, whereTis the type ofX(this distinction is important for assignment compatibility, see Assignment-compatibility). - If

Fis a routine (a function or procedure),@FreturnsF‘s entry point. The type of@Fis always Pointer. - When @ is applied to a method defined in a class, the method identifier must be qualified with the class name. For example,

@TMyClass.DoSomething

- points to the

DoSomethingmethod ofTMyClass. For more information about classes and methods, see Classes and Objects (Delphi).

Note: When using the @ operator, it is not possible to take the address of an interface method, because the address is not known at compile time and cannot be extracted at run time.

Operator Precedence

In complex expressions, rules of precedence determine the order in which operations are performed.

Precedence of operators

| Operators | Precedence |

|---|---|

|

@ |

first (highest) |

|

* |

second |

|

+ |

third |

|

= |

fourth (lowest) |

An operator with higher precedence is evaluated before an operator with lower precedence, while operators of equal precedence associate to the left. Hence the expression:

X + Y * Z

multiplies Y times Z, then adds X to the result; * is performed first, because is has a higher precedence than +. But:

X - Y + Z

first subtracts Y from X, then adds Z to the result; — and + have the same precedence, so the operation on the left is performed first.

You can use parentheses to override these precedence rules. An expression within parentheses is evaluated first, then treated as a single operand. For example:

(X + Y) * Z

multiplies Z times the sum of X and Y.

Parentheses are sometimes needed in situations where, at first glance, they seem not to be. For example, consider the expression:

X = Y or X = Z

The intended interpretation of this is obviously:

(X = Y) or (X = Z)

Without parentheses, however, the compiler follows operator precedence rules and reads it as:

(X = (Y or X)) = Z

which results in a compilation error unless Z is Boolean.

Parentheses often make code easier to write and to read, even when they are, strictly speaking, superfluous. Thus the first example could be written as:

X + (Y * Z)

Here the parentheses are unnecessary (to the compiler), but they spare both programmer and reader from having to think about operator precedence.

Function Calls

Because functions return a value, function calls are expressions. For example, if you have defined a function called Calc that takes two integer arguments and returns an integer, then the function call Calc(24,47) is an integer expression. If I and J are integer variables, then I + Calc(J,8) is also an integer expression. Examples of function calls include:

Sum(A, 63) Maximum(147, J) Sin(X + Y) Eof(F) Volume(Radius, Height) GetValue TSomeObject.SomeMethod(I,J);

For more information about functions, see Procedures and Functions (Delphi).

Set Constructors

A set constructor denotes a set-type value. For example:

[5, 6, 7, 8]

denotes the set whose members are 5, 6, 7, and 8. The set constructor:

[ 5..8 ]

could also denote the same set.

The syntax for a set constructor is:

[ item1, …, itemn ]

where each item is either an expression denoting an ordinal of the set’s base type or a pair of such expressions with two dots (..) in between. When an item has the form x..y, it is shorthand for all the ordinals in the range from x to y, including y; but if x is greater than y, then x..y, the set [x..y], denotes nothing and is the empty set. The set constructor [ ] denotes the empty set, while [x] denotes the set whose only member is the value of x.

Examples of set constructors:

[red, green, MyColor] [1, 5, 10..K mod 12, 23] ['A'..'Z', 'a'..'z', Chr(Digit + 48)]

For more information about sets, see Structured Types (Delphi) in About Data Types (Delphi).

Indexes

Strings, arrays, array properties, and pointers to strings or arrays can be indexed. For example, if FileName is a string variable, the expression FileName[3] returns the third character in the string denoted by FileName, while FileName[I + 1] returns the character immediately after the one indexed by I. For information about strings, see Data Types, Variables and Constants. For information about arrays and array properties, see Arrays in Data Types, Variables, and Constants and «Array Properties» in Properties (Delphi) page.

Typecasts

It is sometimes useful to treat an expression as if it belonged to different type. A typecast allows you to do this by, in effect, temporarily changing an expression’s type. For example, Integer('A') casts the character A as an integer.

The syntax for a typecast is:

typeIdentifier(expression)

If the expression is a variable, the result is called a variable typecast; otherwise, the result is a value typecast. While their syntax is the same, different rules apply to the two kinds of typecast.

Value Typecasts

In a value typecast, the type identifier and the cast expression must both be ordinal or pointer types. Examples of value typecasts include:

Integer('A')

Char(48)

Boolean(0)

Color(2)

Longint(@Buffer)

The resulting value is obtained by converting the expression in parentheses. This may involve truncation or extension if the size of the specified type differs from that of the expression. The expression’s sign is always preserved.

The statement:

I := Integer('A');

assigns the value of Integer('A'), which is 65, to the variable I.

A value typecast cannot be followed by qualifiers and cannot appear on the left side of an assignment statement.

Variable Typecasts

You can cast any variable to any type, provided their sizes are the same and you do not mix integers with reals. (To convert numeric types, rely on standard functions like Int and Trunc.) Examples of variable typecasts include:

Char(I) Boolean(Count) TSomeDefinedType(MyVariable)

Variable typecasts can appear on either side of an assignment statement. Thus:

var MyChar: char; ... Shortint(MyChar) := 122;

assigns the character z (ASCII 122) to MyChar.

You can cast variables to a procedural type. For example, given the declarations:

type Func = function(X: Integer): Integer; var F: Func; P: Pointer; N: Integer;

you can make the following assignments:

F := Func(P); { Assign procedural value in P to F }

Func(P) := F; { Assign procedural value in F to P }

@F := P; { Assign pointer value in P to F }

P := @F; { Assign pointer value in F to P }

N := F(N); { Call function via F }

N := Func(P)(N); { Call function via P }

Variable typecasts can also be followed by qualifiers, as illustrated in the following example:

type

TByteRec = record

Lo, Hi: Byte;

end;

TWordRec = record

Low, High: Word;

end;

PByte = ^Byte;

var

B: Byte;

W: Word;

L: Longint;

P: Pointer;

begin

W := $1234;

B := TByteRec(W).Lo;

TByteRec(W).Hi := 0;

L := $1234567;

W := TWordRec(L).Low;

B := TByteRec(TWordRec(L).Low).Hi;

B := PByte(L)^;

end;

In this example, TByteRec is used to access the low- and high-order bytes of a word, and TWordRec to access the low- and high-order words of a long integer. You could call the predefined functions Lo and Hi for the same purpose, but a variable typecast has the advantage that it can be used on the left side of an assignment statement.

For information about typecasting pointers, see Pointers and Pointer Types (Delphi). For information about casting class and interface types, see «The as Operator» in Class References and Interface References (Delphi).

See Also

- Fundamental Syntactic Elements (Delphi)

- Declarations and Statements (Delphi)

- Boolean short-circuit evaluation (Delphi compiler directive)

- Operator Overloading (Delphi)

- Pointers and Pointer Types (Delphi)

Недавно мы рассказали про язык Delphi — где применяется, что интересного и где он востребован. Теперь перейдём к практике и посмотрим на Delphi изнутри — как он устроен и как на нём программировать. Возможно, уже через пару часов вы начнёте реализовывать свою мечту — писать собственную программу складского учёта.

👉 Если вы проходили «Паскаль» в школе, то вы вряд ли узнаете что-то новое. В этом сила Delphi — это очень простой в освоении язык с поддержкой ООП и почти всех современных парадигм программирования.

О чём пойдёт речь

Комментарии

Переменные

Ввод и вывод данных с клавиатуры

Присваивание и сравнение

Операторные скобки (составной оператор)

Условный оператор if

Оператор множественного выбора case

Цикл с предусловием for

Циклы с предусловием и постусловием

Процедуры

Функции

В Delphi после каждого оператора ставится точка с запятой. Пропускать её нельзя — это будет ошибка и программа не запустится.

Комментарии

Чтобы поставить комментарий в Delphi, раньше использовали только фигурные скобки. Сейчас для комментариев кроме них можно ставить круглую скобку со звёздочкой или два слеша подряд, но с одной стороны:

{ Это комментарий }

(* Это тоже комментарий

на несколько строк *)

// А вот этот комментарий действует только до конца строки

При этом если после { или (* без пробела идёт знак доллара, то это уже не комментарий, а директива компилятору. Это значит, что мы можем переопределить стандартное поведение на то, которое нам нужно, например выключить проверку выхода значений переменной за границы диапазонов:

{$RANGECHECKS OFF}

А так мы превратим нашу программу в консольную, чтобы вся работа шла в командной строке:

{$APPTYPE CONSOLE}

Переменные

Для описания переменной используют ключевое слово var:

var

X: Integer; // переменная целого типа

in, out: string; // две переменных строкового типа

result: Double; // переменная вещественного (дробного) типаБез слова var сразу использовать переменную не получится: компилятор обязательно проверит, объявили ли вы её заранее или нет. Это сделано для контроля над оперативной памятью.

Ввод и вывод данных с клавиатуры

Чаще всего в Delphi делают программы с графическим интерфейсом, где есть поля ввода и кнопки. В этом случае данные получают оттуда, используя свойства разных компонентов. Но если нужно организовать ввод-вывод в консоли, то для этого используют такие команды:

write('Введите координаты X и Y: '); // выводим на экран строку

read(x,y); // считываем переменные x и y

После выполнения каждой команды курсор остаётся на той же строке:

write('Привет!');

write('Это журнал «Код».');

// на экране будет надпись в одну строчку и без пробела: Привет!Это журнал «Код».

Чтобы перенести курсор на новую строку после ввода или вывода, к команде добавляют в конец Ln:

writeLn('Привет!');

writeLn('Это журнал «Код».');

// Привет!

// Это журнал «Код».

Присваивание и сравнение

В отличие от большинства языков программирования, в Delphi оператор присваивания выглядит как двоеточие со знаком равно:

var x: integer;

...

x:=10;

Если вы видите в коде такое, то почти всегда это будет программа на Delphi или Pascal. Сравнение тоже выглядит не так как везде — одинарный символ равенства, как в математике:

:= ← присваивание

= ← сравнение

== ← а вот такого в Delphi нет

Остальные математические команды и операторы сравнения работают как обычно. Логические сравнения пишутся словами:

not ← НЕ

or ← ИЛИ

and ← И

Операторные скобки (составной оператор)

Во многих других языках границы функций, команд в условии и прочие границы обозначаются фигурными скобками, например в JavaScript: function fn() {…}.

А вот в Delphi такие границы задаются отдельными словами begin и end и называются операторными скобками, или составным оператором. Они используются для обозначения границ подпрограмм и там, где язык разрешает ставить только одну команду. Чтобы обойти это ограничение, используют операторные скобки. Простой пример:

if a > b then

begin

что-то полезное

end

else

begin

что-то другое полезное

end

Начало и конец основной программы тоже заключают в операторные скобки.

Условный оператор if

Классический оператор проверки условий, работает так же, как и в других языках:

if <условие> then

<оператор 1>

else

<оператор 2>;

Часть с else — необязательная, если она не нужна, то её можно не писать:

if <условие> then

<оператор 1>;

Так как после then можно ставить только один оператор, то, чтобы поставить больше, используют те самые операторные скобки:

if A > B then

begin

C := A;

writeLn('Первое число больше второго');

writeLn('Останавливаем проверку');

end

else

C := B;Вкладывать условные операторы можно друг в друга сколько угодно.

Оператор множественного выбора case

Если нам нужно выбрать что-то одно сразу из нескольких вариантов, лучше использовать оператор выбора case, который работает так:

- Оператор получает переменную, с которой будет работать, и несколько вариантов её значений.

- Затем по очереди проверяет, совпадает ли очередное значение со значением переменной.

- Как только находится совпадение — выполняется соответствующий оператор, и case на этом заканчивается.

- Если ничего не совпало — то компьютер просто переходит дальше или выполняет то, что написано после else.

Вот как это может выглядеть в коде:

Write('Введите сегодняшнее число');

ReadLn(Day);

case Day of // начинается оператор множественного выбора

1..10: Writeln('Это начало месяца');

11..20: Writeln('Это середина месяца');

21..31: WriteLn('Это конец месяца');

else Writeln('Нет такого дня недели'); // что мы делаем, если ничего не подошло

end; // закончился оператор множественного выбора

Цикл с предусловием for

Особенность этого цикла в том, что мы в нём задаём не условие окончания, а чёткое количество шагов:

for <параметр цикла> := <значение 1> to <значение 2> do <оператор>;

Перевод:

for i := 0 to 99 do что-то полезное;

Логика такая:

- Нам нужно заранее объявить переменную цикла (написать как в JS let i = 1 — не получится).

- Этой переменной мы присваиваем начальное значение и указываем конечное.

- На каждом шаге цикла значение переменной будет автоматически увеличиваться на единицу.

- Как оно превысит конечное значение — цикл остановится.

Выведем числа от 1 до 10:

var I: Integer;

...

for I := 1 to 10 do Writeln(I);Если нам нужно идти наоборот, в сторону уменьшения значения переменной, то вместо to используют downto:

var I: Integer;

...

// выведем числа в обратном порядке, от 10 до 1

for I := 10 downto 1 do Writeln(I);

Циклы с предусловием и постусловием

Эти циклы работают так же, как и в других языках программирования, поэтому освоиться в них будет проще.

Цикл с предусловием — это когда сначала проверяется условие цикла, и если оно верно, то цикл выполняется до тех пор, пока оно не станет ложным. В общем виде такой цикл выглядит так:

while <условие> do

<оператор>;

Выведем с его помощью числа от 1 до 10 (обратите внимание на операторные скобки):

var I: Integer;

...

I:=1;

while I < 11 do

begin

writeLn(I);

I++;

end;Цикл с постусловием работает наоборот: он сначала выполняет тело цикла, а потом проверяет условие. Операторные скобки в нём не ставятся, потому что границы цикла задаются самими командами цикла:

repeat

<оператор 1>;

...

<оператор N>;

until <условие>;

Если условие становится истинным — цикл останавливается. Особенность такого цикла в том, что он выполнится как минимум один раз, прежде чем проверится условие.

var I: Integer;

...

I:=1;

repeat

writeLn(I);

I++;

until I > 10

Процедуры

В Delphi есть отдельный класс подпрограмм, которые называются процедурами. Если сильно упростить, то процедура — это функция, которая не возвращает никакого значения. Процедуры удобно использовать для организации логических блоков, например в одну процедуру вынести приветствие пользователя, в другую — отрисовку интерфейса, в третью — отправку данных на сервер. Все процедуры обязательно должны быть объявлены до начала основной части программы.

В общем виде объявление процедуры выглядит так:

procedure <имя> ( <список параметров, если они нужны> ) ;

const ...; // раздел констант

type ...; // раздел типов

var ...; // раздел переменных

begin // начало процедуры

<операторы>

end; // конец процедуры

Если какой-то раздел в процедуре не нужен, его можно пропустить. Сделаем процедуру, которая будет приветствовать пользователя и спрашивать его имя:

var name: string;

procedure hello; // объявляем процедуру

begin

writeln('Привет! Как тебя зовут? ');

readLn(name);

end;

begin // начало основной программы

hello; // вызываем процедуру

end.В нашем примере имя пользователя попадёт в глобальную переменную name — доступ к глобальным переменным возможен из любого места программы.

Функции

Функции в Delphi работают точно так же, как и во всех остальных языках программирования. Единственное, о чём нужно помнить, — мы должны заранее определить, какой тип данных вернёт нам функция.

Для примера сделаем функцию возведения в степень: мы передаём в неё два числа, а оно возводит первое в нужную степень:

function power(x, y: double): double;

begin

result := Exp(Y * Ln(X)); // возвращаем результат работы функции

end;

begin // начало основной программы

Writeln('5 в степени 6 равно ', power(5, 6));

Readln; // ждём нажатия любой клавиши и выходим из программы

end.Что теперь

Надевайте фланелевую рубашку, заваривайте чай в пакетике, подключайте мышку к порту PS/2 и садитесь программировать. Вам снова 16 лет, на завтра нет домашки, а в кармане свежая карточка на 500 мегабайт интернета.

Вёрстка:

Кирилл Климентьев

Языки программирования

После знакомства с основами объявления переменных и констант и построения простейших структур нам предстоит перейти на очередной уровень освоения языка — научиться использовать в программах операторы и выражения Delphi.

В терминах программирования под выражением понимается логически законченный фрагмент исходного кода программы, предоставляющий способ получения (вычисления) некоторого значения. Простейшим примером выражения может стать строка кода X:=Y+Z, возвращающая результат суммирования двух значений. Предложенное выражение содержит три операнда (X, Y и Z) и два оператора: := и +.

Перечень операторов входящих в состав языка Delphi весьма обширен, при классификации операторов можно выделить следующие группы:

оператор присваивания;

арифметические операторы;

оператор конкатенации строк;

логические операторы;

операторы поразрядного сдвига;

операторы отношения;

операторы множеств;

строковые операторы;

составной оператор;

условные операторы.

Оператор присваивания

Едва ли не самый популярный среди всех операторов Delphi — оператор присваивания нам уже хорошо знаком. Комбинация символов «:=» уже неоднократно встречалась на предыдущих страницах книги, с ее помощью мы передавали значения в переменные. Например,

X:=10; //присвоить переменной X значение 10

Благодаря оператору := в переменной X окажется новое значение.

Арифметические операторы

Как и следует из названия, арифметические операторы необходимы для осуществления математических действий с целыми и вещественными типами данных. Помимо известных еще из курса начальной школы операторов сложения, вычитания, умножения и деления, Delphi обладает еще двумя операторами целочисленного деления (табл. 1.1).

Таблица 1.1. Арифметические операторы Delphi

|

Операто |

Операция |

Входные |

Результат |

Пример |

Результ |

|

р |

значения |

операции |

ат |

||

|

+ |

Сложение |

integer, |

integer, |

X:=3+4; |

7 |

|

double |

double |

||||

|

— |

Вычитание |

integer, |

integer, |

X:=10-3.1; |

8.9 |

|

double |

double |

||||

|

* |

Умножение |

integer, |

integer, |

X:=2*3.2; |

4.4; |

|

double |

double |

||||

|

/ |

Деление |

integer, |

double |

X:=5/2; |

3.5; |

|

double |

1

СКФУ Кафедра компьютерной безопасности

Языки программирования

|

div |

Целочисленно |

integer |

integer |

X:=5 div 2; |

2 |

|

е деление |

|||||

|

mod |

Остаток от |

integer |

integer |

X:=5 mod 2; |

1 |

|

деления |

При объявлении участвующих в расчетах переменных следует учитывать тип данных, возвращаемый в результате выполнения того или иного оператора. Допустим, нам следует разделить число 4 на 2 (листинг 1.1).

var {X:integer; — неподходящий тип данных}

X:extended;{- правильно} begin

X:=4/2; //результат должен быть передан в переменную вещественного типа

WriteLn(X); end.

Даже ученик начальной школы знает, что 4/2=2, другими словами в результате деления мы получим целое число. Однако Delphi обязательно забракует код, если мы попытаемся поместить результат операции деления в целочисленную переменную, и уведомит об этом программиста сообщением, о несовместимости типов.

Примечание

Операторы + и – могут применяться не только для сложения и вычитания, но и для определения знака значения. Например: X:=-5.

Оператор конкатенации строк

Оператор конкатенации строк позволяет объединять две текстовые строки в одну. Для простоты запоминания еще со времен языка Pascal в качестве объединяющего оператора используется тот же самый символ, что и для сложения двух числовых величин — символ плюса + (листинг 1.2).

const S1=’Hello’;

var S:String=’World’;

CH:Char=’!’; begin

S:=S1+’, ‘+S+CH;

WriteLn(S); //’Hello, World!’

ReadLn; end.

Обратите внимание, что оператор конкатенации может быть применен не только для типа данных String, но и к символьному типу Char.

Логические операторы

В табл. 1.2 представлены четыре логических (булевых) оператора, осуществляющих операции логического отрицания, логического «И», логического «ИЛИ» и исключающего «ИЛИ». В результате выполнения любой из логических операций мы можем ожидать только одно значение из двух возможных: истина (true) или ложь (false).

2

СКФУ Кафедра компьютерной безопасности

Языки программирования

Таблица 1.2. Логические операторы Delphi

|

Оператор |

Операция |

Пример |

Результат |

|

NOT |

Логическое отрицание |

var x: boolean = NOT true; |

false |

|

x:= NOT false; |

true |

||

|

AND |

Логическое умножение |

x:=true AND true; |

true |

|

(конъюнкция, логическое «И») |

x:=true and false; |

false |

|

|

для двух выражений |

|||

|

x:=false AND true; |

false |

||

|

x:=false AND false; |

false |

||

|

OR |

Выполняет операцию |

x:=true OR true; |

true |

|

логического «ИЛИ» (сложения) |

|||

|

x:=true OR false; |

false |

||

|

для двух выражений |

|||

|

x:=false OR true; |

true |

||

|

x:=false OR false; |

false |

||

|

XOR |

Выполняет операцию |

x:=true XOR true; |

false |

|

исключающего «ИЛИ» для двух |

x:=true XOR false; |

true |

|

|

выражений |

|||

|

x:=false XOR true; |

true |

||

|

x:=false XOR false; |

false |

Логические операции разрешено проводить с целыми числами. Если вы не забыли порядок перевода чисел из десятичной системы счисления в двоичную и наоборот, то вам наверняка покажется интересным листинг 1.3.

var X,Y,Z : byte; begin

{******* логическое умножение *******}

X:=5; //в бинарном виде 0101

Y:=3; //в бинарном виде 0011

Z:=X AND Y; // 0101 AND 0011 = 0001 {десятичное 1} WriteLn(X,’ AND ‘,Y,’=’,Z);

{******* логическое сложение *******}

X:=1; //в бинарном виде 0001

Y:=2; //в бинарном виде 0010

Z:=X OR Y; // 0001 OR 0010 = 0011 {десятичное 3} WriteLn(X,’ OR ‘,Y,’=’,Z);

{******* исключение или *******}

|

X:=5; |

//в бинарном виде 0101 |

|

|

Y:=3; |

//в бинарном виде 0011 |

|

|

Z:=X XOR Y; // 0101 XOR 0011 = 0110 {десятичное 6} |

||

|

WriteLn(X,’ XOR ‘,Y,’=’,Z); |

||

|

{******* отрицание *******} |

00000001 |

|

|

X:=1; |

//в бинарном виде |

{десятичное 254} |

|

Z:=NOT X; // NOT 00000001 = |

11111110 |

|

|

WriteLn(‘NOT ‘,X,’=’,Z); |

ReadLn; end.

3

СКФУ Кафедра компьютерной безопасности

Языки программирования

Операторы поразрядного сдвига

С отдельными битами значения способны работать операторы поразрядного сдвига SHL и SHR. Первый из операторов осуществляет сдвиг влево (после оператора указывается количество разрядов сдвига), второй — поразрядный сдвиг вправо.

В листинге 1.4 представлен фрагмент кода, демонстрирующий возможности операторов сдвига.

var i:integer=1; begin

while true do begin

i:=i SHL 1; //сдвиг влево на 1 разряд

WriteLn(i);

if i>=1024 then break; //выход из цикла end;

readln; end.

Если вы запустите программу на выполнение, то получите весьма нетривиальный результат. Оператор сдвига обрабатывает исходное значение, равное 1 (в двоичном представлении 00000001). Каждый шаг цикла сдвигает единичку на одну позицию влево. В итоге на экране компьютера отобразится следующий столбик значений:

2 {что в двоичном представлении соответствует 00000010}

|

4 |

{00000100} |

|

8 |

{00001000} |

|

16 |

{00010000} |

|

32 |

{00100000} |

|

64 |

{01000000} |

и т. д.

По сути, мы с вами реализовали программу, позволяющую возводить значение 2 в заданную степень.

Можете провести эксперимент, приводящий к прямо противоположному результату. Для этого проинициализируйте переменную i значением 2 в степени N (например, 210 = 1024), замените оператор SHL на SHR и перепишите условие выхода из цикла: if i<1 then break.

Операторы отношения

Операторы отношения (неравенства) обычно применяются для сравнения двух числовых значений, в результате сравнения возвращаются логические значения true/false (табл. 1.3). Операторы отношения — желанные гости в условных операторах.

Таблица 1.3. Операторы отношения

|

Оператор |

Операция |

Пример |

Результат |

|

= |

Сравнение |

10=5 |

false |

|

<> |

Неравенство |

10<>5 |

true |

|

> |

Больше чем |

10>5 |

true |

|

< |

Меньше чем |

10<5 |

false |

|

>= |

Больше или равно |

10>=5 |

true |

|

<= |

Меньше или равно |

10<=5 |

false |

4

СКФУ Кафедра компьютерной безопасности

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #