Board of Directors

Brian T. Moynihan

Chair of the Board and Chief Executive Officer,

Bank of America Corporation

View Bio

Brian T. Moynihan

Chair of the Board and Chief Executive Officer,

Bank of America Corporation

As our Chief Executive Officer, Mr. Moynihan leads a team of more than 210,000 employees focused on driving Responsible Growth for our teammates, clients, communities, and shareholders. Under his leadership, the company provides core financial services to three client groups through our eight lines of business. This has delivered record earnings and significant capital return to shareholders. Mr. Moynihan has demonstrated leadership qualities, management capability, knowledge of our business and industry, and a long-term strategic perspective. In addition, he has many years of international and domestic financial services experience, including wholesale and retail businesses.

Professional Highlights

- Appointed Chair of the Board of Directors of Bank of America Corporation in October 2014 and President and Chief Executive Officer in January 2010. Prior to becoming Chief Executive Officer, Mr. Moynihan ran each of the company’s operating units

- Member (and prior Chair) of the Board of Directors of Bank Policy Institute (Chair of the Global Regulatory Policy Committee)

- Member (and prior Chair) of Financial Services Forum

- Chair of the Supervisory Board of The Clearing House Association L.L.C.

- Member of Business Roundtable

- Member (and prior Chairman) of the World Economic Forum’s International Business Council (Chair of Stakeholder Capitalism Metrics Initiative)

- Chairman of the Board of The U.S. Council on Competitiveness

- Former Member (and prior President) of the Federal Advisory Council of the Federal Reserve Board

- Chair of the Sustainable Markets Initiative

Other Leadership Experience

- Member of Board of Fellows of Brown University (Chair of the Watson Institute Board of Governors)

- Member of Advisory Council of Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture

- Member of Charlotte Executive Leadership Council

- Chairman of Massachusetts Competitive Partnership

Lionel L. Nowell III

Lead Independent Director,

Bank of America Corporation;

Former Senior Vice President and Treasurer, PepsiCo, Inc. (Pepsi)

View Bio

Lionel L. Nowell III

Lead Independent Director,

Bank of America Corporation;

Former Senior Vice President and Treasurer, PepsiCo, Inc. (Pepsi)

Mr. Nowell is an active board leader with a deep range of corporate audit, financial expertise, risk management, operational, and strategic planning experience. During his more than 30-year career with multinational consumer products conglomerates, he oversaw the worldwide corporate treasury functions, including debt and investment activities, capital markets strategies, and foreign exchange as Senior Vice President and Treasurer of Pepsi, finance functions as Chief Financial Officer of Pepsi Bottling Group, and held responsibilities for strategy and business development as a Senior Vice President at RJR Nabisco. Mr. Nowell brings a robust corporate governance and board leadership perspective through his current and prior service on public company boards across varying industries and through his ongoing dialogue with institutional shareholders as our Board’s Lead Independent Director.

Professional Highlights

- Served as Senior Vice President and Treasurer of Pepsi, a leading global food, snack, and beverage company, from 2001 to May 2009, and as Chief Financial Officer of The Pepsi Bottling Group and Controller of Pepsi

- Served as Senior Vice President, Strategy and Business Development at RJR Nabisco, Inc. from 1998 to 1999

- Held various senior financial roles at the Pillsbury division of Diageo plc, including Chief Financial Officer of its Pillsbury North America, Pillsbury Foodservice, and Häagen-Dazs divisions, and also served as Controller and Vice President of Internal Audit of the Pillsbury Company

- Served as Lead Director of the Board of Directors of Reynolds American, Inc. from January 2017 to July 2017 and as a Board member from September 2007 to July 2017

- Served as a member of the Board of Directors of American Electric Power Company, Inc., chair of its Audit Committee, member of its Directors and Corporate Governance, Policy, Executive, and Finance Committees

- Member of the Board of Directors of Ecolab Inc. and its Audit Committee and Finance Committee

- Member of the Board of Directors of Textron Inc. and Chair of its Audit Committee

- As our Board’s Lead Independent Director Mr. Nowell has an extensive set of responsibilities that brings him into frequent communications with our primary regulators, institutional shareholders, other stakeholders and our employees and customers.

- In 2022, Mr. Nowell was named “Independent Director of the Year” by Corporate Board Member

Other Leadership Experience

- Dean’s Advisory Council at The Ohio State University Fisher College of Business

Sharon L. Allen

Former Chairman,

Deloitte LLP (Deloitte)

View Bio

Sharon L. Allen

Former Chairman,

Deloitte LLP (Deloitte)

Ms. Allen is an experienced director who brings deep auditing and consulting services, financial reporting, and corporate governance experience to our Board. As a corporate leader, Ms. Allen has broad experience leading and working with large, complex businesses and brings an international perspective on risk management and strategic planning. During her nearly 40-year career with Deloitte, the largest professional services organization in the U.S. and member firm of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited (DTTL), she became the first woman elected to serve as Chairman of the Board and also served as a member of DTTL’s Global Board of Directors, the chair of its Global Risk Committee, and the U.S. representative of its Global Governance Committee. During her tenure at Deloitte, Ms. Allen oversaw relationships with major multinational corporations and provided oversight and guidance to management.

Professional Highlights

- Served as Chairman of Deloitte, a firm that provides audit, consulting, financial advisory, risk management, and tax services, as the U.S. member firm of DTTL from 2003 to 2011

- Employed at Deloitte for nearly 40 years in various leadership roles, including Partner and Regional Managing Partner, responsible for audit and consulting services for a number of Fortune 500 and large private companies

- Former member of the Board of Directors of First Solar, Inc. and its Technology Committee, and Chair of its Audit Committee

- Member of the Board of Directors of Albertsons Companies, Inc. and its Audit & Risk Committee, and Chair of its Governance, Compliance & ESG Committee

- Member of the Global Board of Directors, Chair of the Global Risk Committee, and U.S. Representative on the Global Governance Committee of DTTL from 2003 to 2011

Other Leadership Experience

- Former Director and Chair of the National Board of Directors of the YMCA of the USA, a leading nonprofit organization for youth development, healthy living, and social responsibility

- Former Vice Chair of the Board of Trustees of the Autry National Center, the governing body of the Autry Museum of the American West

- Appointed by President George W. Bush to the President’s Export Council, which advised the President on export enhancement

José (Joe) E. Almeida

Chairman, President, and Chief Executive Officer, Baxter International Inc. (Baxter)

View Bio

José (Joe) E. Almeida

Chairman, President, and Chief Executive Officer, Baxter International Inc. (Baxter)

Mr. Almeida is an active chief executive officer and public company director with experience leading large, global companies subject to regulatory oversight. His service as a board member in a variety of industries also brings additional perspectives to our Board. As Chairman, President, and Chief Executive Officer of Baxter, Mr. Almeida is leading the company through a period of transformation driven by innovation, operational excellence, and strategic execution. Prior to joining Baxter, Mr. Almeida served as chairman, president and chief executive officer of Covidien plc and served in leadership roles at Tyco Healthcare (Covidien’s predecessor), Wilson Greatbatch Technologies Inc., American Home Products’ Acufex Microsurgical division, and Johnson & Johnson’s Professional Products division. He began his career as a management consultant at Andersen Consulting (Accenture) and previously served on the boards of Walgreens Boots Alliance, Inc., Analog Devices, Inc., EMC Corporation, State Street Corporation and Covidien plc.

Professional Highlights

- Chairman of the Board, President and CEO of Baxter, a global medtech leader, effective January 1, 2016. Began serving as an executive officer of Baxter in October 2015

- Served as Senior Advisor with The Carlyle Group, a multinational private equity, alternative asset management and financial services corporation, from May 2015 to October 2015

- Served as the Chairman, President and Chief Executive Officer of Covidien, a global healthcare products company, from March 2012 through January 2015, prior to the acquisition of Covidien by Medtronic plc, and President and Chief Executive Officer of Covidien from July 2011 to March 2012

- Prior to becoming Covidien’s President and Chief Executive officer, served in several leadership roles at Covidien, including President of its Worldwide Medical Devices business; also served as President of International and Vice President of Global Manufacturing for Covidien’s predecessor, Tyco Healthcare

- Served on the boards of directors of: Walgreens Boots Alliance, Inc. from 2017 to 2022, including on its Compensation Committee; State Street Corporation from 2013 to 2015, including on its Executive Compensation Committee; Analog Devices, Inc. during 2015; and EMC Corporation from 2014 to 2015

- Served on the Board of Trustees of Partners in Health from 2013 to 2021

Other Leadership Experience

- Serves on the Board of Trustees of Northwestern University

Frank P. Bramble, Sr.

Former Executive Vice Chairman,

MBNA Corporation (MBNA)

View Bio

Frank P. Bramble, Sr.

Former Executive Vice Chairman,

MBNA Corporation (MBNA)

Mr. Bramble is a veteran financial services executive with broad-ranging financial services experience, and international perspective. He also brings institutional insights to our Board, having held leadership positions at two financial services companies acquired by our company (MBNA, acquired in 2006, and MNC Financial Inc., acquired in 1993). As a former executive officer of one of the largest credit card issuers in the U.S. and a major regional bank, Mr. Bramble has dealt with a wide range of issues important to our company, including risk management, credit cycles, sales and marketing to consumers, corporate governance, and audit and financial reporting.

Professional Highlights

- Served as Chairman of the Board of Trustees from July 2014 to June 2016 and Interim President from July 2013 to June 2014 of Calvert Hall College High School in Baltimore, Maryland

- Served as Executive Vice Chairman from July 2002 to April 2005 and Advisor to the Executive Committee from April 2005 to December 2005 of MBNA Corporation, a financial services company acquired by Bank of America in January 2006

- Previously served as the Chairman, President, and Chief Executive Officer at Allfirst Financial, Inc., MNC Financial Inc., Maryland National Bank, American Security Bank, and Virginia Federal Savings Bank

- Served as a member of the Board of Directors, from April 1994 to May 2002, and Chairman, from December 1999 to May 2002, of Allfirst Financial, Inc. and Allfirst Bank, U.S. subsidiaries of Allied Irish Banks, p.l.c.

- Began his career as an audit clerk at the First National Bank of Maryland

Other Leadership Experience

- Emeritus member of the Board of Visitors of Towson University and guest lecturer in business strategy and accounting from 2006 to 2008

Pierre J. P. de Weck

Former Chairman and Global Head of Private Wealth Management, Deutsche Bank AG

View Bio

Pierre J. P. de Weck

Former Chairman and Global Head of Private Wealth Management, Deutsche Bank AG

Mr. de Weck is a Swiss national based in Europe with deep knowledge of the global financial services industry. As a senior executive with a tenure of nearly three decades in global financial services, including as a member of the Group Executive Committee and Global Head of Private Management of Deutsche Bank AG in London, and as Chief Executive Officer of North America, Chief Executive Officer of Europe, and a member of the Group Executive Board at UBS AG, and as Chief Executive Officer of UBS Capital, Mr. de Weck has extensive experience in risk management, including credit risk management. He brings valuable international perspective to our company’s business activities, including to our European subsidiaries through his service on the Boards of Directors of Merrill Lynch International (MLI), our U.K. broker-dealer subsidiary, and BofA Securities Europe S.A. (BofASE), our French broker-dealer subsidiary.

Professional Highlights

- Served as the Chairman and Global Head of Private Wealth Management and as a member of the Group Executive Committee of Deutsche Bank AG from 2002 to May 2012

- Served on the Management Board of UBS from 1994 to 2001; as Head of Institutional Banking from 1994 to 1997; as Chief Credit Officer and Head of Private Equity from 1998 to 1999; and as Head of Private Equity from 2000 to 2001

- Held various senior management positions at Union Bank of Switzerland, a predecessor firm of UBS, from 1985 to 1994

- Chair of the Board of Directors of MLI (and previously chair of the MLI Board’s Risk Committee), and Chair of the Board of Directors of BofASE

Arnold W. Donald

Former President and Chief Executive Officer,

Carnival Corporation and Carnival plc (Carnival)

View Bio

Arnold W. Donald

Former President and Chief Executive Officer,

Carnival Corporation and Carnival plc (Carnival)

Mr. Donald has more than three decades of strategic planning, global operations, and risk management experience in regulated, consumer, retail, and distribution businesses, including through his service as President and Chief Executive Officer of Carnival, one of the world’s largest leisure travel companies with operations worldwide, his leadership roles with global responsibilities at Monsanto, and his experience as a public company director. Through his leadership of non-profit organizations, including The Executive Leadership Council and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation International, Mr. Donald also brings focus and perspective on our work to promote equality, diversity and inclusion, and advance economic opportunity for our employees and the communities we serve.

Professional Highlights

- President, Chief Executive Officer, and Chief Climate Officer of Carnival, a cruise and vacation company from July 2013 to November 2022; began serving on Carnival’s Board of Directors in 2001

- Served as President and Chief Executive Officer from November 2010 to June 2012 of The Executive Leadership Council, a nonprofit organization providing a professional network and business forum to African-American executives at major U.S. companies

- President and Chief Executive Officer of the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation International from January 2006 to February 2008

- Served as Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of Merisant from 2000 to 2003, a privately held global manufacturer of tabletop sweeteners, and remained as Chairman until 2005

- Joined Monsanto in 1977 and held several senior leadership positions with global responsibilities, including President of its Agricultural Group and President of its Nutrition and Consumer Sector, over a more than 20-year tenure

- Served as a member of the Board of Directors of Crown Holdings, Inc. and member of its Compensation Committee; served as a member of the Board of Directors of Carnival and member of its Executive Committee

- Member of the Board of Directors of Salesforce, Inc.

Other Leadership Experience

- Appointed by President Clinton and re-appointed by President George W. Bush to the President’s Export Council

Linda P. Hudson

Former Chairman and Chief Executive Officer,

The Cardea Group, LLC;

Former President and Chief Executive Officer,

BAE Systems, Inc. (BAE)

View Bio

Linda P. Hudson

Former Chairman and Chief Executive Officer,

The Cardea Group, LLC;

Former President and Chief Executive Officer,

BAE Systems, Inc. (BAE)

Ms. Hudson has extensive executive leadership experience. She brings international perspective, geopolitical insights, and broad knowledge in strategic planning, global operations, and risk management to our Board through a career in the defense, aerospace, and security industries that spanned more than 40 years. As the former President and Chief Executive Officer of BAE and the first woman to lead a major national security corporation, Ms. Hudson oversaw a global, highly regulated, and complex U.S.-based defense, aerospace, and security company, wholly owned by London-based BAE Systems plc (BAE Systems), where she also served as an executive director. Through her leadership positions, including with General Dynamics Corporation and its armament and technical products division, Ms. Hudson also brings focus and perspective to the Board’s oversight of technology and related risks, including cybersecurity risks.

Professional Highlights

- Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of The Cardea Group, LLC, a management consulting business, from May 2014 to January 2020

- Served as CEO Emeritus of BAE, a U.S.-based subsidiary of BAE Systems, a global defense, aerospace, and security company headquartered in London, from February 2014 to May 2014, and as President and Chief Executive Officer of BAE from October 2009 until January 2014

- Served as President of BAE Systems’ Land and Armaments operating group, the world’s largest military vehicle and equipment business, from October 2006 to October 2009

- Prior to joining BAE, served as Vice President of General Dynamics Corporation and President of its Armament and Technical Products business; held various positions in engineering, production operations, program management, and business development for defense and aerospace companies

- Served as a member of the Executive Committee and as an executive director of BAE Systems from 2009 until January 2014 and as a member of the Board of Directors of BAE from 2009 to April 2015

- Served as a member of the Board of Directors of The Southern Company and its Nominating, Governance and Corporate Responsibility Committee and Operations, Environmental and Safety Committee from 2014 to July 2018

- Member of the Board of Directors of Trane Technologies plc (formerly Ingersoll-Rand plc) and its Compensation Committee, Sustainability, Corporate Governance and Nominating Committee, and Technology and Innovation Committee

- Member of the Board of Directors of TPI Composites, Inc. and its Nominating and Corporate Governance Committee and Technology Committee

Other Leadership Experience

- Elected member to the National Academy of Engineering, one of the highest professional honors accorded an engineer

- Member of the Board of Directors of the University of Florida Foundation, Inc. and the advisory board of the University of Florida Engineering Leadership Institute

- Former member of the Charlotte Center Executive Board for the Wake Forest University School of Business

- Former member of the Board of Trustees of Discovery Place, a nonprofit education organization dedicated to inspiring exploration of the natural and social world

- Member of the Board of Directors of UF Health, the health care system affiliated with the University of Florida College of Medicine

Monica C. Lozano

Former Chief Executive Officer, College Futures Foundation;

Former Chairman, US Hispanic Media Inc;

Lead Independent Director, Target Corporation

View Bio

Monica C. Lozano

Former Chief Executive Officer, College Futures Foundation;

Former Chairman, US Hispanic Media Inc;

Lead Independent Director, Target Corporation

Ms. Lozano has a broad range of leadership experience in public and private sectors and a track record as a champion for equality, opportunity, and representation. As Chief Executive Officer of College Futures Foundation, a charitable foundation focused on increasing the rate of bachelor’s degree completion among California student populations who are low-income and have had a historically low college success rate, she worked to increase the rate of college graduation and improve opportunity for low-income students and students of color in California. With 30 years at La Opinión, the largest Spanish-language newspaper in the U.S., including as editor and publisher, as Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of its parent company, ImpreMedia LLC, and as co-founder of the Aspen Institute Latinos and Society Program, Ms. Lozano possesses deep insights into the issues that impact the Hispanic-Latino community. As a director serving on the boards of large organizations with diversified international operations, including Apple Inc. and Target Corporation, and previously The Walt Disney Company, Ms. Lozano has long standing experience overseeing matters ranging from corporate governance, human capital management, executive compensation, to risk management and financial reporting. In addition, as a member of California’s Task Force on Jobs and Business Recovery, Ms. Lozano provides valuable perspective on important public policy, societal, and economic issues relevant to our company.

Professional Highlights

- Chief Executive Officer of College Futures Foundation from December 2017 to July 2022 and member of the Board of Directors from December 2019 to July 2022

- Served as Chair of the Board of Directors of U.S. Hispanic Media Inc., the parent company of ImpreMedia, a leading Hispanic news and information company, from June 2014 to January 2016

- Served as Chairman of ImpreMedia from July 2012 to January 2016, Chief Executive Officer from May 2010 to May 2014, and Senior Vice President from January 2004 to May 2010

- Served as Publisher of La Opinión, a subsidiary of ImpreMedia and the leading Spanish–language daily print and online newspaper in the U.S., from 2004 to May 2014, and Chief Executive Officer from 2004 to July 2012

- Lead Independent Director of the Board of Directors of Target Corporation and member of its Governance & Sustainability Committee, Chair of its Compensation & Human Capital Management Committee

- Member of the Board of Directors of Apple Inc. and its Audit and Finance Committee

Other Leadership Experience

- Member of California’s Task Force on Jobs and Business Recovery

- Served as a member of President Obama’s Council on Jobs and Competitiveness from 2011 to 2012 and served on President Obama’s Economic Recovery Advisory Board from 2009 to 2011

- Serves on and former Chair of the Board of Directors of the Weingart Foundation

- Served as the Chair of the Board of Regents of the University of California, as a member of the Board of Trustees of The Rockefeller Foundation, as a member of the Board of Trustees of the University of Southern California, and as a member of the State of California Commission on the 21st Century Economy

Denise L. Ramos

Former Chief Executive Officer and President, ITT Inc. (ITT)

View Bio

Denise L. Ramos

Former Chief Executive Officer and President, ITT Inc. (ITT)

Ms. Ramos is an experienced public company executive who brings global business leadership, financial expertise, and strategic planning experience to our Board. Ms. Ramos served as Chief Executive Officer of ITT, a diversified manufacturer of engineered components and customized technology solutions for the transportation, industrial, and energy markets, focusing on innovation and technology. She was Chief Financial Officer at ITT, Furniture Brands International, and the U.S. KFC division of Yum! Brands, and served as the corporate treasurer at Yum! Brands. Through her public company board service on the Boards of Phillip 66 and Raytheon Technologies, Ms. Ramos brings board-level insights into issues facing complex, regulated global public companies and oversight experience in finance, audit, corporate governance, public policy, and sustainability.

Professional Highlights

- Chief Executive Officer and President of ITT, a diversified manufacturer of critical components and customized technology solutions, from 2011 to 2019; Senior Vice President and Chief Financial Officer of ITT from 2007 to 2011

- Served as Chief Financial Officer for Furniture Brands International, a former home furnishings company, from 2005 to 2007

- Served in various roles at Yum! Brands Inc., an American fast-food company, from 2000 to 2005, including Chief Financial Officer of the U.S. Division of KFC Corporation and as Senior Vice President and Treasurer

- Began her career at Atlantic Richfield Company, where she spent 21 years in a number of finance positions

- Member of the Board of Directors of Phillips 66 and its Audit and Finance, Nominating and Governance, and Executive Committees, and Chair of its Public Policy and Sustainability Committee

- Member of the Board of Directors of Raytheon Technologies Corporation and its Audit and Human Capital and Compensation Committees

Clayton S. Rose

President, Bowdoin College

View Bio

Clayton S. Rose

President, Bowdoin College

Dr. Rose is an executive leader in academics and the private sector, who brings public policy and social thought leadership, and broad global financial services, strategic, and risk management experiences to our Board. As President of Bowdoin College, Dr. Rose has a legacy advancing diversity, equity, and inclusion; increasing access and opportunity for students; addressing mental health challenges facing youth; and promoting sustainability. During his tenure on the faculty of the Harvard Business School, Dr. Rose taught and wrote on issues of leadership, ethics, the financial crisis, and the role of business in society. Dr. Rose spent the first 20 years of his career with JPMorgan Chase & Co. and its predecessor company, where he retired as Vice Chairman after holding leadership positions in investment banking, equities, securities, derivatives, and corporate finance divisions and leading the company’s diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives. Following retirement from JPMorgan Chase, Dr. Rose received a master’s degree and PhD with distinction in sociology from the University of Pennsylvania focusing on issues of race in America. Dr. Rose has served on several financial institutions boards and currently serves as Chair of the Board of Trustees of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the U.S.’s largest private supporter of academic biomedical research.

Professional Highlights

- President of Bowdoin College; retirement announced for June 30, 2023

- Held various other roles in academia, including Professor of Management Practice at Harvard Business School

- Served as Vice Chairman, headed two lines of business– Global Investment Banking and Global Equities–and was a member of JPMorgan Chase’s senior management team during his approximately 20-year tenure at JPMorgan Chase

- Served as a member of the Boards of Directors of XL Group, plc, Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac), and Mercantile Bankshares Corp.

Other Leadership Experience

- Trustee and Chair of the Board of Trustees for Howard Hughes Medical Institute and formerly Chair of the Audit and Compensation Committee

- Served on the company’s Board of Directors from 2013 to 2015

Michael D. White

Former Chairman, President and Chief Executive Officer, DIRECTV;

Lead Director, Kimberly-Clark Corporation

View Bio

Michael D. White

Former Chairman, President and Chief Executive Officer, DIRECTV;

Lead Director, Kimberly-Clark Corporation

Mr. White is a seasoned executive and public company director who, as Chief Executive Officer of DIRECTV, led the global operations and strategic direction of complex and highly regulated multinational consumer retail and distribution businesses. He possesses executive and board leadership experience and provides broad ranging operational and strategic insights, an international perspective, and financial expertise to our Board. Mr. White was President, Chief Executive Officer and Chairman of the board of directors of DIRECTV, where he oversaw the operations and strategic direction of the company in the U.S. and in Latin America. Prior to joining DIRECTV, he served as the Chief Executive Officer of PepsiCo International; Frito-Lay’s Europe, Africa, and Middle East division; and Snack Ventures Europe, PepsiCo’s partnership with General Mills International. He also served as Chief Financial Officer of PepsiCo., Inc., Pepsi-Cola Company worldwide, and Frito-Lay International. Mr. White began his career as a management consultant at Bain & Company and Arthur Andersen & Co. Mr. White currently is a director on boards of public companies with extensive global operations where he holds board leadership positions.

Professional Highlights

- Served as Chairman, President and Chief Executive Officer of DIRECTV, a leading provider of digital television entertainment services, from January 2010 to August 2015, and as a Director of the company from November 2009 until August 2015

- Chief Executive Officer of PepsiCo International from February 2003 until November 2009; and served as Vice Chairman and director of PepsiCo from March 2006 to November 2009, after holding positions of increasing importance with PepsiCo since 1990

- Served as Senior Vice President at Avon Products, Inc.

- Served as a Management Consultant at Bain & Company and Arthur Andersen & Co.

- Lead Director of the Board of Directors of Kimberly-Clark Corporation, Chair of its Executive Committee; Member of the Board of Directors of Whirlpool Corporation, Chair of its Audit Committee, and member of its Corporate Governance and Nominating Committee

Other Leadership Experience

- Member of the Boston College Board of Trustees

- Vice Chair of The Partnership to End Addiction

Thomas D. Woods

Former Vice Chairman and Senior Executive Vice President,

Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce (CIBC);

Former Chairman, Hydro One Limited

View Bio

Thomas D. Woods

Former Vice Chairman and Senior Executive Vice President,

Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce (CIBC);

Former Chairman, Hydro One Limited

Mr. Woods is a veteran financial services executive with experience in risk management, corporate strategy, finance, and the corporate and investment banking businesses. Mr. Woods began his nearly 40-year tenure at CIBC and its predecessor firms in its investment banking department and later served as Head of Canadian Corporate Banking, Chief Financial Officer, and Chief Risk Officer, before retiring as Vice Chairman. As Senior Executive Vice President and Chief Risk Officer of CIBC during the financial crisis, Mr. Woods focused on risk management and CIBC’s risk culture. He chaired CIBC’s Asset Liability Committee, served as CIBC’s lead liaison with regulators, and was an active member of CIBC’s business strategy group.

Professional Highlights

- Served as Vice Chairman and Senior Executive Vice President of CIBC, a leading Canada-based global financial institution, from July 2013 until his retirement in December 2014

- Served as Senior Executive Vice President and Chief Risk Officer of CIBC from 2008 to July 2013, and Senior Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer of CIBC from 2000 to 2008

- Employed at Wood Gundy, a CIBC predecessor firm, starting in 1977; served in various senior leadership positions, including as Controller of CIBC, as Chief Financial Officer of CIBC World Markets (CIBC’s investment banking division), and as the Head of CIBC’s Canadian Corporate Banking division

- Served as Chair of the Board of Directors of Hydro One Limited, an electricity transmission and distribution company serving the Canadian province of Ontario, and publicly traded and listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange, from August 2018 to July 2019

- Member of the Board of Directors of MLI, chair of its Risk Committee, and member of its Governance Committee

Other Leadership Experience

- Member of the Board of Directors of Alberta Investment Management Corporation, a Canadian institutional investment fund manager, and on the advisory committee of Cordiant Capital Inc., a fund manager specializing in emerging markets

- Member of the University of Toronto College of Electors, and the Board of Advisors of the University of Toronto Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering

- Former member of the Board of Directors of Jarislowsky Fraser Limited, a global investment management firm, from 2016 to 2018, former member of the Boards of Directors of DBRS Limited and DBRS, Inc., an international credit rating agency, from 2015 to 2016, and former member of the Board of Directors of TMX Group Inc., a Canada-based financial services company, from 2012 to 2014

R. David Yost

Former CEO, AmerisourceBergen Corporation

View Bio

R. David Yost

Former CEO, AmerisourceBergen Corporation

Mr. Yost’s roles as the former Chief Executive Officer of AmerisourceBergen Corporation (AmerisourceBergen) and its predecessor company enable him to bring his broad experience in strategic planning, regulated industries, risk management, and operational risk to our Board. In addition, Mr. Yost has experience leading a large, complex business. Through his service on public company boards, he has board-level experience overseeing large, complex public companies in various industries, which provides him with valuable insights on corporate governance, human capital management, and risk management.

Professional Highlights

- Served as Chief Executive Officer of AmerisourceBergen, a pharmaceutical services company providing drug distribution and related services to healthcare providers and pharmaceutical manufacturers, from 2001 until his retirement in July 2011, and as President from 2001 to 2002 and again from September 2007 to November 2010

- Held various positions at AmerisourceBergen and its predecessor companies during a nearly 40-year career, including Chief Executive Officer from 1997 to 2001 and Chairman from 2000 to 2001 of Amerisource Health Corporation

- Member of the Board of Directors of Johnson Controls International plc and its Audit Committee

- Member of the Board of Directors of Marsh & McLennan Companies, Inc., and its Compensation Committee, Directors and Governance Committee, and Finance Committee

Maria T. Zuber

Vice President for Research and E.A. Griswold Professor of Geophysics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)

View Bio

Maria T. Zuber

Vice President for Research and E.A. Griswold Professor of Geophysics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)

Dr. Zuber is a distinguished research scientist and academic leader who brings a breadth of risk management, technology, geopolitical insights, and strategic planning thought leadership to our Board. Dr. Zuber is the first woman to lead a science department at MIT and the first woman to lead a NASA planetary mission. In her role as Vice President for Research at MIT, Dr. Zuber oversees multiple interdisciplinary research laboratories and centers focusing on cancer research, energy and environmental solutions initiatives, plasma science and fusion, electronics, nanotechnology, and radio science and technology. She also leads MIT’s Climate Action Plan, and is responsible for intellectual property, research integrity and compliance, and research relationships with the federal government. Dr. Zuber has held leadership roles on 10 space exploratory missions with NASA. She also served on the National Science Board under President Obama and President Trump and is currently Co-Chair of President Biden’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology.

Professional Highlights

- Vice President for Research at MIT, a leading research institution, since 2013, where she oversees MIT Lincoln Laboratory and more than a dozen interdisciplinary research laboratories and centers and leads MIT’s Climate Action Plan

- Served as a Professor at MIT since 1995, and was Head of the Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences Department from 2003 to 2011

- Served in a number of positions at NASA, including as a Geophysicist from 1986 to 1992, a Senior Research Scientist from 1993 to 2010, and as Principal Investigator of the Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory (GRAIL) mission from 2008 to 2017, which was designed to create the most accurate gravitational map of the moon to date and give scientists insight into the moon’s internal structure, composition, and evolution, and held leadership roles associated with scientific experiments or instrumentation on 10 NASA missions

- Member of the Board of Directors of Textron Inc. and its Nominating and Corporate Governance, and Organization and Compensation Committees

Other Leadership Experience

- Appointed by President Biden in 2021 as Co-Chair of the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology

- Appointed by President Obama in 2013 and reappointed by President Trump in 2018 to the National Science Board, a 25-member panel that serves as the governing board of the National Science Foundation and as advisors to the President and Congress on policy matters relating to science and engineering; served as Board Chair from 2016 to 2018

- Co-Chair of the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine’s National Science, Technology and Security Roundtable

- Chair of NASA’s Mars Sample Return Mission Standing Review Board

- Board of Directors and Executive Committee of The Massachusetts Green High Performance Computing Center, a joint venture by Massachusetts universities, which provides infrastructure for computationally intensive research

- Board of Trustees of Brown University

- Email Alerts

- Contacts

- RSS News Feed

- Terms of use

Ошибка воспроизведения видео. Пожалуйста, обновите ваш браузер.

Новости·

10 сен 2021, 18:27

0

0

Bank of America объявил об изменениях в составе высшего руководства. Об этом сообщается в пресс-релизе банка.

Банк заявил о добавлении пяти новых членов, включая трех женщин, в команду высшего руководства, что еще больше усиливает разнообразие на самых высоких уровнях компании. После всех изменений в состав высшего руководства Bank of America войдут люди со средним стажем работы в компании 21 год и 31 год — в сфере финансовых услуг.

Больше новостей об инвестициях вы найдете в нашем аккаунте в Instagram

Лидеры роста

Лидеры падения

Валюты

Товары

Индексы

Курсы валют ЦБ РФ

| Bank of America Corporation | |

| |

|

|

|

| Тип | Публичная компания |

|---|---|

| Листинг на бирже |

NYSE: BAC TYO: 8648 |

| Основание | 1928 |

| Основатели | Амадео Джаннини[d] |

| Расположение |

|

| Ключевые фигуры | Брайан Мойнихэн (председатель, президент и CEO)[1] |

| Отрасль | Финансовые услуги |

| Продукция |

Кредитование Страхование Управление активами |

| Собственный капитал | ▲ $256 млрд (2015)[2] |

| Оборот | ▼ $83,416 млрд (2015 год)[2] |

| Чистая прибыль | ▲ $15,888 млрд (2015 год)[2] |

| Активы | ▲ $2,144 трлн (2015 год)[2] |

| Капитализация | ▲ $232 млрд (2017)[3] |

| Число сотрудников | 213 000 (2015 год)[2] |

| Материнская компания | BlackRock |

| Дочерние компании | Merrill Lynch, Bank of America Merrill Lynch[d], Endeavour Foundation[d], First Franklin Financial Corp.[d], Incapital[d] и Seafirst Bank[d] |

| Аудитор | PricewaterhouseCoopers |

| Сайт | www.bankofamerica.com |

Bank of America (рус. Бэнк оф Америка) — американский финансовый конгломерат, оказывающий широкий спектр финансовых услуг частным и юридическим лицам, крупнейшая банковская холдинговая компания в США по числу активов[4], занимает 23-е место среди крупнейших компаний мира по версии Forbes (2015 год).[5] Компания ведёт деятельность во всех 50 штатах, а также в 35 других странах, у неё 4700 отделений, 213 000 сотрудников и 16 000 банкоматов; зарегистрирована в штате Делавэр под названием Bank of America Corporation.[2]

14 сентября 2008 года Bank of America объявил о покупке инвестиционного банка Merrill Lynch. Стоимость покупки по информации газеты Уолл-стрит джорнал составила $50 млрд.[6]

Bank of America 29 августа 2011 года объявил о намерении продать 13,1 млрд акций China Construction Bank группе частных инвесторов за $8,3 млрд.[7]

По соглашению с министерством юстиции США, достигнутому в августе 2014 года Bank of America Corporation выплатит штраф в размере $16,65 млрд, чтобы дело о нарушениях при продаже банком ипотечных бумаг в период до кризиса 2008 года не было передано в суд.[8]

Содержание

- 1 История

- 1.1 Банк Италии, Сан-Франциско

- 1.2 Банк Америки, Сан-Франциско

- 1.3 NationsBank, Шарлотт

- 1.4 Банк Америки, Шарлотт

- 2 Деятельность

- 2.1 Подразделения

- 2.2 География деятельности

- 3 Руководство

- 4 Акционеры

- 5 Примечания

- 6 Литература

- 7 Ссылки

История

Банк Италии, Сан-Франциско

В 1904 году сын итальянских эмигрантов Амадео Джаннини (англ.)русск. основал в Сан-Франциско банк под названием Bank of Italy, предназначенный для работы среди многочисленных итальянских эмигрантов. Банк Италии проявил большую активность по восстановлению Сан-Франциско после катастрофического землетрясения 1906 года. Джаннини применил несколько инноваций в банковской сфере, в частности, он одним из первых сделал упор на обслуживание «среднего класса», открыл большое количество отделений банка, которых к 1927 году насчитывалось более 100. В 1929 году он осуществил слияние своего банка с расположенным в Лос-Анджелесе Банком Америки. Объединённый банк принял имя последнего.

Банк Америки, Сан-Франциско

К этому времени Банк Америки стал крупнейшим банком США. Операции Джаннини вышли далеко за пределы Калифорнии при помощи основанной им в 1928 году Transamerica Corporation (англ.)русск., которая владела ключевым пакетом акций самого Банка Америки.

После отставки в 1945 году Амадео Джаннини дело продолжил его сын Лоренс Джаннини[9], ставший президентом банка ещё в 1936 году. С его смертью, совпавшей с победой на президентских выборах в США Республиканской партии, для Банка Америки настали трудные времена.

С принятием нового антимонопольного законодательства (Закона Клейтона и Закона о банковских холдинговых компаниях (англ.)русск.) Банк Америки и Transamerica Corporation в 1953 году были разделены. Из Transamerica Corporation в 1957 году выделилась компания First Interstate Bancorp (англ.)русск., поглощённая в 1996 году Wells Fargo. Transamerica Corporation, занявшаяся исключительно страховым бизнесом, была в 1999 году куплена нидерландской Aegon. Сам Банк Америки ограничил свои операции рамками Калифорнии.

С 1958 года Банк Америки стал выпускать кредитные карты, из которых выросли современные карты VISA. В ответ группа банков, группировавшаяся вокруг Wells Fargo, выпустили в 1966 году MasterCard.

В 1983 году Банк Америки вновь вышел за пределы Калифорнии, приобретя Seafirst Bank (англ.)русск. в Сиэтле. Но уже в 1986—1987 годах он понёс большие потери и с трудом отбил атаку собственного «отпрыска» — First Interstate Bancorp, попытавшейся завладеть Банком Америки. В 1990-х годах, приобретя ряд банков (включая калифорнийский Security Pacific Bank (англ.)русск., чикагский Continental Illinois (англ.)русск.), Банк Америки по размеру вкладов вновь стал обширнейшим банком США, но в 1997 году предоставил 1,4 млрд долларов США нью-йоркской D. E. Shaw & Co. (англ.)русск., и это привело к катастрофе. Деньги пропали в результате экономического кризиса в России в 1998 году, и сам Банк Америки был куплен шарлоттским NationsBank.

NationsBank, Шарлотт

Был основан в 1874 году в городе Шарлотте штата Северная Каролина под именем Commercial National Bank (англ.)русск., в 1957 году объединился со своим многолетним шарлоттским соперником American Trust Co. под именем American Commercial Bank, ставший в 1960 году после слияния с Security National Bank называться Carolina National Bank (англ.)русск..

Все эти годы банк оставался финансовым учреждением местного значения. Лишь в 1982 году было сделано первое приобретение за пределами Северной Каролины — куплен First National Bank of Lake City. В следующем году банк возглавил Хью МакКолл (англ.)русск., начавший совместно с шарлоттским First Union Corporation (англ.)русск. и другими дружественными банками энергичную экспансию.

Было приобретено более 200 различных банков, включая такие крупные как First RepublicBank Corporation of Dallas (1988) и C&S/Sovran Corp (1991), после чего банк был переименован в NationsBank и продолжил экспансию, поглотив Maryland National Corporation (1992), Chicago Research and Trading Group (1993), BankSouth (1995), St. Louis-based Boatmen’s Bancshares (1996), Jacksonville, Florida based Barnett Bank (1997), Montgomery Securities (1997), и, наконец, Банк Америки (1998), приняв имя последнего. Штаб-квартира банка была оставлена в Шарлотте.

Банк Америки, Шарлотт

В 1999 году МакКолл передал текущие операции своему преемнику Кену Луису (англ.)русск., унаследовавшему в 2001 году от него посты CEO, председатель совета директоров и президента Банка Америки.

Экспансия банка продолжалась. В 2004 году был куплен FleetBoston Financial (англ.)русск., в который слились большинство банков Новой Англии, в 2005 году — мерилендский MBNA (англ.)русск.. Из-за этого произошёл конфликт с шарлоттской Wachovia, который с 2001 года стал называться FirstUnion Bank. Wachovia уступил, получив 100 млн долларов США отступного.

И наконец, в 2008 году во время мирового экономического кризиса был куплен Merrill Lynch. Последнее вызвало резкие нападки на Банк Америки вследствие выявившегося слишком поздно бедственного состояния покупки и тем, что она приобреталась на средства, выделенные правительством на борьбу с финансовым кризисом. В результате Кен Луис был вынужден с 29 апреля 2009 года передать пост председателя совета директоров Уолтеру Мэсси (англ.)русск. и к концу года уйти в отставку. На посту СЕО Банка Америки его заменил с 1 января 2010 года Брайан Мойнихэн (англ.)русск., присоединившийся к Банку Америки вместе с ФлитБостон банком.

Деятельность

Подразделения

Bank of America состоит из пяти основных подразделений:

- Потребительский банкинг (Consumer Banking) — оборот в 2015 году составил $31 млрд, чистая прибыль — $6.7 млрд, активы — $636 млрд. Включает депозитную деятельность (обслуживание сберегательных счетов клиентов) и потребительское кредитование. Услуги предоставляются частным лицам и мелким предпринимателям в США через сеть из 4700 отделений, 16 тысяч банкоматов, также через мобильные и интернет-приложения.

- Глобальное управление активами (Global Wealth & Investment Management) — оборот в 2015 году составил $18 млрд, чистая прибыль — $2,6 млрд, активы — $296 млрд. Подразделение состоит из двух дочерних компаний: Merrill Lynch Global Wealth Management (из поглощённой в 2008 году Merrill Lynch) и U.S. Trust.

Bank of America оказывает доверительное управление через дочерние компании Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith Inc. с активами $650 млрд и Managed Account Advisors LLC с активами $250 млрд.[10] Общая сумма активов под управлением на конец 2015 года составила около $900 млрд.

- Глобальный банкинг (Global Banking) — оборот в 2015 году составил $17 млрд, чистая прибыль — $5.3 млрд, активы — $382 млрд. Занимается обслуживанием крупных корпораций, компаний и некоммерческих организаций. Предоставляет кредиты, размещает акции и проводит финансовые консультации.

- Глобальные рынки (Global Markets) — оборот в 2015 году составил $15 млрд, чистая прибыль — $2.5 млрд, активы — $552 млрд. Осуществляет торговлю на фондовых, валютных и товарно-сырьевых биржах.

- Ипотечное кредитование (Legacy Assets & Servicing) — оборот в 2015 году составил $3.43 млрд, чистый убыток — $740 млн (в 2014 году убыток составил $13 млрд), активы — $47 млрд. Занимается кредитованием и перекредитованием покупки недвижимости. Портфолио ипотечных кредитов на конец 2015 года составило $565 млрд.

География деятельности

По сравнению с другими глобальными финансовыми конгломератами Bank of America имеет небольшое количество зарубежных дочерних обществ и представительств, большинство из них ранее входили в Merrill Lynch (и продолжают носить это название). В России есть дочерняя компания OOO Merrill Lynch Securities[2] и представительство в Москве[11].

| Год | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Оборот | 19,904 | 20,117 | 20,505 | 27,96 | 30,737 | 72,776 | 66,833 | 72,782 | 119,643 | 110,22 | 93,454 | 83,334 | 88,942 | 84,247 | 82,507 |

| Чистая прибыль | 7,499 | 9,553 | 10,762 | 13,947 | 16,465 | 21,133 | 14,982 | 4,008 | 6,276 | -2,238 | 1,446 | 4,188 | 11,431 | 4,833 | 15,888 |

| Активы | 645 | 654 | 749 | 1045 | 1270 | 1467 | 1602 | 1844 | 2443 | 2440 | 2296 | 2191 | 2164 | 2146 | 2160 |

| Собственный капитал | 48,7 | 47,9 | 50,1 | 84,8 | 100 | 130 | 137 | 165 | 245 | 233 | 229 | 236 | 234 | 238 | 252 |

| Капитализация | 116 | 190 | 185 | 238 | 183 | 70 | 130 | 135 | 56 | 125 | 165 | 188 | 175 |

В списке крупнейших публичных компаний мира Forbes Global 2000 за 2015 год корпорация Bank of America заняла 23-е место, в том числе 11-е по активам, 37-е по рыночной капитализации, 67-е по выручке и 123-е по чистой прибыли, а также 72-е место в списке самых дорогих брендов.[5]

Руководство

- Брайан Мойнихен (Brian Moynihan) — председатель правления (с 2014 года), президент и главный исполнительный директор (с 2010 года) Bank of America. Родился 9 октября 1959 года в городе Мариетта (штат Огайо), США. Окончил Брауновский университет и Университет Нотр-Дам. С 1993 года работал в финансовой компании FleetBoston Financial, когда она была в 2004 году поглощена Bank of America, вошёл в состав руководства Банка Америки.[1][14]

Акционеры

Крупнейшие владельцы акций Bank of America на 31 марта 2017 года.[15][16]

| Название акционера | Количество акций | Процент |

|---|---|---|

| BlackRock Capital Management, Inc. | 668,154,405 | 6.68 |

| The Vanguard Group, Inc. | 652,377,332 | 6.53 |

| State Street Global Advisors, Inc. | 455,832,976 | 4.56 |

| FMR Co., Inc. | 321,239,866 | 3.21 |

| Wellington Management Company LLP | 198,685,780 | 1.99 |

| Dodge & Cox | 185,448,539 | 1.86 |

| J.P. Morgan Investment Management Inc. | 171,260,328 | 1.71 |

| State Street Global Advisors (Australia) Limited | 115,933,214 | 1.16 |

| Mellon Capital Management Corporation | 112,593,104 | 1.13 |

| Northern Trust Investments, Inc. | 111,384,618 | 1.12 |

| Norges Bank Investment Management | 102,091,486 | 1.02 |

| Geode Capital Management, LLC | 99,829,926 | 1.00 |

| Invesco Advisers, Inc. | 96,252,517 | 0.96 |

| Harris Associates | 94,067,258 | 0.94 |

| Korea Investment Corporation | 78,517,674 | 0.79 |

| Boston Partners Global Investors, Inc. | 75,404,921 | 0.76 |

| Goldman Sachs Asset Management, L.P. | 65,985,656 | 0.66 |

| Barrow, Hanley, Mewhinney & Strauss, LLC | 65,412,883 | 0.66 |

| TIAA-CREF Investment Management, LLC | 62,555,507 | 0.63 |

| Morgan Stanley Smith Barney LLC | 61,936,587 | 0.62 |

| Dimensional Fund Advisors L.P. | 59,983,709 | 0.60 |

| AllianceBernstein L.P. | 57,485,617 | 0.58 |

| Columbia Management Investment Advisers, LLC | 52,968,022 | 0.53 |

| Legal & General Investment Management America Inc. | 49,789,644 | 0.50 |

| Lansdowne Partners (UK) LLP | 47,767,227 | 0.48 |

| UBS Asset Management (Americas) Inc. | 40,119,416 | 0.40 |

| T. Rowe Price Associates, Inc. | 38,760,769 | 0.39 |

| Canada Pension Plan Investment Board | 36,027,412 | 0.36 |

| The Manufacturers Life Insurance Company | 34,524,634 | 0.35 |

| Capital World Investors | 34,028,000 | 0.34 |

Примечания

- ↑ 1 2 People: Bank of America Corp (англ.). Reuters. Проверено 2 апреля 2016.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Annual Report 2015 (SEC Filing Form 10-K) (англ.). Bank of America Corporation. Проверено 2 апреля 2016.

- ↑ Bank of America Corp — Quote (англ.). Reuters. Проверено 2 апреля 2016.

- ↑ 50 крупнейших банковских холдинговых компаний США (англ.). Федеральная резервная система. Проверено 30 марта 2011. Архивировано 18 февраля 2012 года.

- ↑ 1 2 Рейтинг Forbes global 2000 за 2015 год (англ.). Forbes. Проверено 3 апреля 2015.

- ↑ Заметка о покупке в Уолл-стрит джорнал (англ.)

- ↑ Bank of America продаст группе частных инвесторов 13,1 млрд акций китайского China Construction Bank за $8,3 млрд долл. // 29.08.2011

- ↑ BofA выплатит $16,7 млрд за урегулирование дела о нарушениях в ипотечной сфере в США // 21 августа 2014 года

- ↑ Lawrence Mario Giannini, 1894—1952

- ↑ BANK OF AMERICA Institutional Portfolio (англ.). NASDAQ.com. Проверено 31 декабря 2016.

- ↑ Фирма BANK OF AMERICA NA (США) (рус.). 2Msk/ru. Проверено 4 апреля 2016.

- ↑ Annual Report 2006 (SEC Filing Form 10-K) (англ.). Bank of America Corporation (16 March 2006). Проверено 2 апреля 2016.

- ↑ Annual Report 2010 (SEC Filing Form 10-K) (англ.). Bank of America Corporation (25 February 2011). Проверено 2 апреля 2016.

- ↑ Todd Wallace. Moynihan, in running for Bank of America’s top job, has experience winning tough fights (англ.). Boston Globe (17 November 2009). Проверено 2 апреля 2016.

- ↑ [http://www.nasdaq.com/symbol/bac/institutional-holdings Bank of America Corporation (BAC) Institutional Ownership &

Holdings] (англ.). NASDAQ.com. Проверено 31 марта 2017. - ↑ BAC — информация о владельцах для Bank of America Corporation (рус.). MSN Финансы. Проверено 31 марта 2017.

Литература

- Грег Фаррелл. Крах титанов: История о жадности и гордыне, о крушении Merrill Lynch и о том, как Bank of America едва избежал банкротства = Crash Of The Titans Greed, Hubris, The Fall Of Merrill Lynch, And The Near-Collapse Of Bank Of America. — М.: Альпина Паблишер, 2014. — 412 с. — ISBN 978-5-9614-4746-0.

Ссылки

- Официальный сайт банка (англ.)

- Bank of America Corp на сайте Securities and Exchange Commission

This article is about a commercial bank unaffiliated with any government. For the central bank of the United States, see Federal Reserve System.

«BofA» redirects here. For the French illustrator, see Gus Bofa.

«Bofa» redirects here. For snake species in the monotypic genus Bofa, see Bofa erlangeri.

The Bank of America Corporate Center, headquarters of Bank of America in Charlotte, North Carolina |

|

| Type | Public company |

|---|---|

|

Traded as |

|

| ISIN | US0605051046 |

| Industry | Financial services |

| Predecessors |

|

| Founded |

|

| Founders |

|

| Headquarters | Bank of America Corporate Center Charlotte, North Carolina, U.S. |

|

Number of locations |

3,900 retail financial centers & approximately 16,000 ATMs |

|

Area served |

Worldwide |

|

Key people |

|

| Services |

|

| Revenue | |

|

Operating income |

|

|

Net income |

|

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

| Owners | Berkshire Hathaway (12.8%) |

|

Number of employees |

c. 217,000 (2022) |

| Divisions |

|

| Website | bankofamerica.com |

| Footnotes / references [1][2] |

The Bank of America Corporation (often abbreviated BofA or BoA) is an American multinational investment bank and financial services holding company headquartered at the Bank of America Corporate Center in Charlotte, North Carolina, with investment banking and auxiliary headquarters in Manhattan. The bank was founded in San Francisco, California. It is the second-largest banking institution in the United States, after JPMorgan Chase, and the second-largest bank in the world by market capitalization. Bank of America is one of the Big Four banking institutions of the United States.[3] It serves approximately 10.73% of all American bank deposits, in direct competition with JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup, and Wells Fargo. Its primary financial services revolve around commercial banking, wealth management, and investment banking.

One branch of its history stretches back to the U.S.-based Bank of Italy, founded by Amadeo Pietro Giannini in 1904, which provided various banking options to Italian immigrants who faced service discrimination.[4] Originally headquartered in San Francisco, California, Giannini acquired Banca d’America e d’Italia (Bank of America and Italy) in 1922. The passage of landmark federal banking legislation facilitated a rapid growth in the 1950s, quickly establishing a prominent market share. After suffering a significant loss after the 1998 Russian bond default, BankAmerica, as it was then known, was acquired by the Charlotte-based NationsBank for US$62 billion. Following what was then the largest bank acquisition in history, the Bank of America Corporation was founded. Through a series of mergers and acquisitions, it built upon its commercial banking business by establishing Merrill Lynch for wealth management and Bank of America Merrill Lynch for investment banking in 2008 and 2009, respectively (since renamed BofA Securities).[5]

Both Bank of America and Merrill Lynch Wealth Management retain large market shares in their respective offerings. The investment bank is considered within the «Bulge Bracket» as the third largest investment bank in the world, as of 2018.[6] Its wealth management side manages US$1.081 trillion in assets under management (AUM) as the second largest wealth manager in the world, after UBS.[7] In commercial banking, Bank of America operates—but does not necessarily maintain—retail branches in all 50 states of the United States, the District of Columbia and more than 40 other countries.[8] Its commercial banking footprint encapsulates 46 million consumer and small business relationships at 4,600 banking centers and 15,900 automated teller machines (ATMs).

The bank’s large market share, business activities, and economic impact has led to numerous lawsuits and investigations regarding both mortgages and financial disclosures dating back to the 2008 financial crisis. Its corporate practices of servicing the middle class and wider banking community has yielded a substantial market share since the early 20th century. As of August 2018, Bank of America has a $313.5 billion market capitalization, making it the 13th largest company in the world. As the sixth largest American public company, it garnered $102.98 billion in sales as of June 2018.[9] Bank of America was ranked #25 on the 2020 Fortune 500 rankings of the largest US corporations by total revenue.[10] Likewise, Bank of America was also ranked #8 on the 2020 Global 2000 rankings done by Forbes. Bank of America was named the «World’s Best Bank» by the Euromoney Institutional Investor in their 2018 Awards for Excellence.[11][12]

History[edit]

The Bank of America name first appeared in 1923, with the formation in California of Bank of America, Los Angeles. In 1928, this entity was acquired by Bank of Italy of San Francisco, which took the Bank of America name two years later.[13]

The eastern portion of the Bank of America franchise can be traced to 1784, when Massachusetts Bank was chartered, the first federally chartered joint-stock owned bank in the United States and only the second bank to receive a charter in the United States. This bank became FleetBoston, with which Bank of America merged in 2004. In 1874, Commercial National Bank was founded in Charlotte. That bank merged with American Trust Company in 1958 to form American Commercial Bank.[14] Two years later it became North Carolina National Bank when it merged with Security National Bank of Greensboro. In 1991, it merged with C&S/Sovran Corporation of Atlanta and Norfolk to form NationsBank.

The central portion of the franchise dates to 1910, when Commercial National Bank and Continental National Bank of Chicago merged in 1910 to form Continental & Commercial National Bank, which evolved into Continental Illinois National Bank & Trust.

Bank of Italy[edit]

The history of Bank of America dates back to October 17, 1904, when Amadeo Pietro Giannini founded the Bank of Italy, in San Francisco.[13] In 1922, Bank of America, Los Angeles was established with Giannini as a minority investor. The two banks merged in 1928 and consolidated with other bank holdings to create what would become the largest banking institution in the country.[15] In 1918, another corporation, Bancitaly Corporation, was organized by A. P. Giannini, the largest stockholder of which was Stockholders Auxiliary Corporation.[citation needed] This company acquired the stocks of various banks located in New York City and certain foreign countries.[citation needed]

In 1928, Giannini merged his bank with Bank of America, Los Angeles, headed by Orra E. Monnette. Bank of Italy was renamed on November 3, 1930, to Bank of America National Trust and Savings Association,[16] which was the only such designated bank in the United States at that time. Giannini and Monnette headed the resulting company, serving as co-chairs.[17]

Expansion in California[edit]

Giannini introduced branch banking shortly after 1909 legislation in California allowed for branch banking in the state, establishing the bank’s first branch outside San Francisco in 1909 in San Jose. By 1929 the bank had 453 banking offices in California with aggregate resources of over US$1.4 billion.[18] There is a replica of the 1909 Bank of Italy branch bank in History Park in San Jose, and the 1925 Bank of Italy Building is an important downtown landmark. Giannini sought to build a national bank, expanding into most of the western states as well as into the insurance industry, under the aegis of his holding company, Transamerica Corporation. In 1953 regulators succeeded in forcing the separation of Transamerica Corporation and Bank of America under the Clayton Antitrust Act.[19] The passage of the Bank Holding Company Act of 1956 prohibited banks from owning non-banking subsidiaries such as insurance companies. Bank of America and Transamerica were separated, with the latter company continuing in the insurance sector. However, federal banking regulators prohibited Bank of America’s interstate banking activity, and Bank of America’s domestic banks outside California were forced into a separate company that eventually became First Interstate Bancorp, later acquired by Wells Fargo and Company in 1996. Only in the 1980s, with a change in federal banking legislation and regulation, could Bank of America again expand its domestic consumer banking activity outside California.

New technologies also allowed the direct linking of credit cards with individual bank accounts. In 1958, the bank introduced the BankAmericard, which changed its name to Visa in 1977.[20]

A coalition of regional bankcard associations introduced Interbank in 1966 to compete with BankAmericard. Interbank became Master Charge in 1966 and then MasterCard in 1979.[21]

Expansion outside California[edit]

Following the passage of the Bank Holding Company Act of 1956 by the US Congress,[22] BankAmerica Corporation was established for the purpose of owning and operating Bank of America and its subsidiaries.

Bank of America expanded outside California in 1983, with its acquisition, orchestrated in part by Stephen McLin, of Seafirst Corporation of Seattle, Washington, and its wholly owned banking subsidiary, Seattle-First National Bank.[23] Seafirst was at risk of seizure by the federal government after becoming insolvent due to a series of bad loans to the oil industry. BankAmerica continued to operate its new subsidiary as Seafirst rather than Bank of America until the 1998 merger with NationsBank.[23]

BankAmerica experienced huge losses in 1986 and 1987 due to the placement of a series of bad loans in the Third World. The company fired its CEO, Sam Armacost in 1986. Though Armacost blamed the problems on his predecessor, A.W. (Tom) Clausen, Clausen was appointed to replace Armacost.[citation needed] The losses resulted in a huge decline of BankAmerica stock, making it vulnerable to a hostile takeover. First Interstate Bancorp of Los Angeles (which had originated from banks once owned by BankAmerica), launched such a bid in the fall of 1986, although BankAmerica rebuffed it, mostly by selling operations.[24] It sold its FinanceAmerica subsidiary to Chrysler and the brokerage firm Charles Schwab and Co. back to Mr. Schwab. It also sold Bank of America and Italy to Deutsche Bank. By the time of the 1987 stock-market crash, BankAmerica’s share price had fallen to $8, but by 1992 it had rebounded mightily to become one of the biggest gainers of that half-decade.[citation needed]

BankAmerica’s next big acquisition came in 1992. The company acquired Security Pacific Corporation and its subsidiary Security Pacific National Bank in California and other banks in Arizona, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington, which Security Pacific had acquired in a series of acquisitions in the late 1980s. This represented, at the time, the largest bank acquisition in history.[25] Federal regulators, however, forced the sale of roughly half of Security Pacific’s Washington subsidiary, the former Rainier Bank, as the combination of Seafirst and Security Pacific Washington would have given BankAmerica too large a share of the market in that state. The Washington branches were divided and sold to West One Bancorp (now U.S. Bancorp) and KeyBank.[26] Later that year, BankAmerica expanded into Nevada by acquiring Valley Bank of Nevada.[27]

In 1994, BankAmerica acquired the Continental Illinois National Bank and Trust Co. of Chicago. At the time, no bank possessed the resources to bail out Continental, so the federal government operated the bank for nearly a decade.[28] Illinois then regulated branch banking extremely heavily, so Bank of America Illinois was a single-unit bank until the 21st century. BankAmerica moved its national lending department to Chicago in an effort to establish a financial beachhead in the region.[29]

These mergers helped BankAmerica Corporation to once again become the largest U.S. bank holding company in terms of deposits, but the company fell to second place in 1997 behind North Carolina’s fast-growing NationsBank Corporation, and to third in 1998 behind First Union Corp.[citation needed]

Bank of America logo used from 1998 to 2018

On the capital markets side, the acquisition of Continental Illinois helped BankAmerica to build a leveraged finance origination- and distribution business, which allowed the firm’s existing broker-dealer, BancAmerica Securities (originally named BA Securities), to become a full-service franchise.[30] In addition, in 1997, BankAmerica acquired Robertson Stephens, a San Francisco–based investment bank specializing in high technology for $540 million.[31] Robertson Stephens was integrated into BancAmerica Securities, and the combined subsidiary was renamed «BancAmerica Robertson Stephens».[32]

Merger of NationsBank and BankAmerica[edit]

Logo of the former Bank of America (BA), 1969–1998

In 1997, BankAmerica lent hedge fund D. E. Shaw & Co. $1.4 billion in order to run various businesses for the bank.[33] However, D.E. Shaw suffered significant loss after the 1998 Russia bond default.[34][35] NationsBank of Charlotte acquired BankAmerica in October 1998 in what was the largest bank acquisition in history at that time.[36]

While NationsBank was the nominal survivor, the merged bank took the better-known name of Bank of America. Hence, the holding company was renamed Bank of America Corporation, while NationsBank, N.A. merged with Bank of America NT&SA to form Bank of America, N.A. as the remaining legal bank entity.[37] The combined bank operates under Federal Charter 13044, which was granted to Giannini’s Bank of Italy on March 1, 1927. However, the merged company was and still is headquartered in Charlotte, and retains NationsBank’s pre-1998 stock price history. All U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) filings before 1998 are listed under NationsBank, not Bank of America. NationsBank president, chairman, and CEO Hugh McColl, took on the same roles with the merged company.[citation needed]

In 1998, Bank of America possessed combined assets of $570 billion, as well as 4,800 branches in 22 U.S. states.[citation needed] Despite the size of the two companies, federal regulators insisted only upon the divestiture of 13 branches in New Mexico, in towns that would be left with only a single bank following the combination.[38] The broker-dealer, NationsBanc Montgomery Securities, was named Banc of America Securities in 1998.[citation needed]

2001 to present[edit]

Typical Bank of America branch in Los Angeles

In 2001, McColl stepped down and named Ken Lewis as his successor.

In 2004, Bank of America announced it would purchase Boston-based bank FleetBoston Financial for $47 billion in cash and stock.[39] By merging with Bank of America, all of its banks and branches were given the Bank of America logo. At the time of merger, FleetBoston was the seventh largest bank in United States with $197 billion in assets, over 20 million customers and revenue of $12 billion.[39] Hundreds of FleetBoston workers lost their jobs or were demoted, according to The Boston Globe.

On June 30, 2005, Bank of America announced it would purchase credit card giant MBNA for $35 billion in cash and stock. The Federal Reserve Board gave final approval to the merger on December 15, 2005, and the merger closed on January 1, 2006. The acquisition of MBNA provided Bank of America a leading domestic and foreign credit card issuer. The combined Bank of America Card Services organization, including the former MBNA, had more than 40 million U.S. accounts and nearly $140 billion in outstanding balances. Under Bank of America, the operation was renamed FIA Card Services.

Bank of America operated under the name BankBoston in many other Latin American countries, including Brazil. In May 2006, Bank of America and Banco Itaú (Investimentos Itaú S.A.) entered into an acquisition agreement, through which Itaú agreed to acquire BankBoston’s operations in Brazil, and was granted an exclusive right to purchase Bank of America’s operations in Chile and Uruguay, in exchange for Itaú shares. The deal was signed in August 2006.

Prior to the transaction, BankBoston’s Brazilian operations included asset management, private banking, a credit card portfolio, and small, middle-market, and large corporate segments. It had 66 branches and 203,000 clients in Brazil. BankBoston in Chile had 44 branches and 58,000 clients and in Uruguay, it had 15 branches. In addition, there was a credit card company, OCA, in Uruguay, which had 23 branches. BankBoston N.A. in Uruguay, together with OCA, jointly served 372,000 clients. While the BankBoston name and trademarks were not part of the transaction, as part of the sale agreement, they cannot be used by Bank of America in Brazil, Chile or Uruguay following the transactions. Hence, the BankBoston name has disappeared from Brazil, Chile and Uruguay. The Itaú stock received by Bank of America in the transactions has allowed Bank of America’s stake in Itaú to reach 11.51%. Banco de Boston de Brazil had been founded in 1947.

On November 20, 2006, Bank of America announced the purchase of The United States Trust Company for $3.3 billion, from the Charles Schwab Corporation. US Trust had about $100 billion of assets under management and over 150 years of experience. The deal closed July 1, 2007.[40]

On September 14, 2007, Bank of America won approval from the Federal Reserve to acquire LaSalle Bank Corporation from ABN AMRO for $21 billion. With this purchase, Bank of America possessed $1.7 trillion in assets. A Dutch court blocked the sale until it was later approved in July. The acquisition was completed on October 1, 2007. Many of LaSalle’s branches and offices had already taken over smaller regional banks within the previous decade, such as Lansing and Detroit-based Michigan National Bank. The acquisition also included the Chicago Marathon event, which ABN AMRO acquired in 1996. Bank of America took over the event starting with the 2007 race.

The deal increased Bank of America’s presence in Illinois, Michigan, and Indiana by 411 branches, 17,000 commercial bank clients, 1.4 million retail customers, and 1,500 ATMs. Bank of America became the largest bank in the Chicago market with 197 offices and 14% of the deposit share, surpassing JPMorgan Chase.

LaSalle Bank and LaSalle Bank Midwest branches adopted the Bank of America name on May 5, 2008.[41]

Ken Lewis, who had lost the title of chairman of the board, announced that he would retire as CEO effective December 31, 2009, in part due to controversy and legal investigations concerning the purchase of Merrill Lynch. Brian Moynihan became president and CEO effective January 1, 2010, and afterward credit card charge offs and delinquencies declined in January. Bank of America also repaid the $45 billion it had received from the Troubled Assets Relief Program.[42][43]

Acquisition of Countrywide Financial[edit]

On August 23, 2007, the company announced a $2 billion repurchase agreement for Countrywide Financial. This purchase of preferred stock was arranged to provide a return on investment of 7.25% per annum and provided the option to purchase common stock at a price of $18 per share.[44]

On January 11, 2008, Bank of America announced that it would buy Countrywide Financial for $4.1 billion.[45] In March 2008, it was reported that the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) was investigating Countrywide for possible fraud relating to home loans and mortgages.[46] This news did not hinder the acquisition, which was completed in July 2008,[47] giving the bank a substantial market share of the mortgage business, and access to Countrywide’s resources for servicing mortgages.[48] The acquisition was seen as preventing a potential bankruptcy for Countrywide. Countrywide, however, denied that it was close to bankruptcy. Countrywide provided mortgage servicing for nine million mortgages valued at $1.4 trillion as of December 31, 2007.[49]

This purchase made Bank of America Corporation the leading mortgage originator and servicer in the U.S., controlling 20–25% of the home loan market.[50] The deal was structured to merge Countrywide with the Red Oak Merger Corporation, which Bank of America created as an independent subsidiary. It has been suggested that the deal was structured this way to prevent a potential bankruptcy stemming from large losses in Countrywide hurting the parent organization by keeping Countrywide bankruptcy remote.[51] Countrywide Financial has changed its name to Bank of America Home Loans.

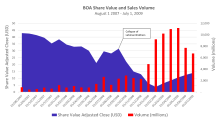

Chart showing the trajectory of BOA share value and transaction volume during the 2007–2009 financial crisis

In December 2011, the Justice Department announced a $335 million settlement with Bank of America over discriminatory lending practice at Countrywide Financial. Attorney General Eric Holder said a federal probe found discrimination against qualified African-American and Latino borrowers from 2004 to 2008. He said that minority borrowers who qualified for prime loans were steered into higher-interest-rate subprime loans.[52]

Acquisition of Merrill Lynch[edit]

On September 14, 2008, Bank of America announced its intention to purchase Merrill Lynch & Co., Inc. in an all-stock deal worth approximately $50 billion. Merrill Lynch was at the time within days of collapse, and the acquisition effectively saved Merrill from bankruptcy.[53] Around the same time Bank of America was reportedly also in talks to purchase Lehman Brothers, however a lack of government guarantees caused the bank to abandon talks with Lehman.[54] Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy the same day Bank of America announced its plans to acquire Merrill Lynch.[55] This acquisition made Bank of America the largest financial services company in the world.[56] Temasek Holdings, the largest shareholder of Merrill Lynch & Co., Inc., briefly became one of the largest shareholders of Bank of America, with a 3% stake.[57] However, taking a loss Reuters estimated at $3 billion, the Singapore sovereign wealth fund sold its whole stake in Bank of America in the first quarter of 2009.[58]

Shareholders of both companies approved the acquisition on December 5, 2008, and the deal closed January 1, 2009.[59] Bank of America had planned to retain various members of the then Merrill Lynch’s CEO, John Thain’s management team after the merger.[60] However, after Thain was removed from his position, most of his allies left. The departure of Nelson Chai, who had been named Asia-Pacific president, left just one of Thain’s hires in place: Tom Montag, head of sales and trading.[61]