Муниципальное автономное общеобразовательное учреждение

«Средняя общеобразовательная школа №15»

Эссе на тему «История Стилей Руководства Фиделя Кастро»

Гусакова И.Е.

Учитель литературы, истории и обществознания

В этой статье будет

обсуждаться краткая история Фиделя Кастро, его стили руководства,

характеристики и определяющие факторы, которые произошли во время его

восхождения к известности. Это обеспечивает его источники власти и

дополнительно исследует его эффективность или неэффективность как лидера.

Исследование Фиделя Кастро и его руководства проводилось с помощью

онлайн-источников, в том числе трех академических.

Важность:

Какую связь можно было

бы найти между Фиделем Кастро, его последователями и ситуацией? Каковы были его

воспринимаемые положительные и отрицательные качества? Какие выдающиеся черты

можно было бы обнаружить в Фиделе Кастро?

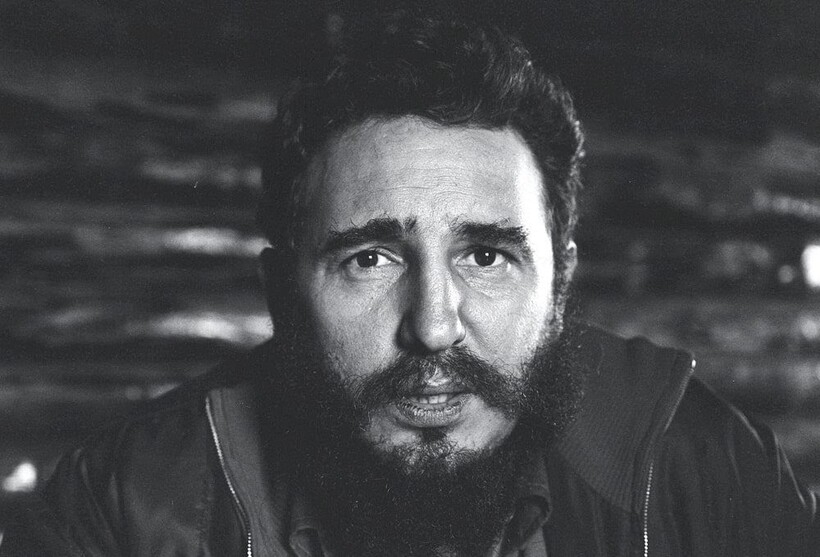

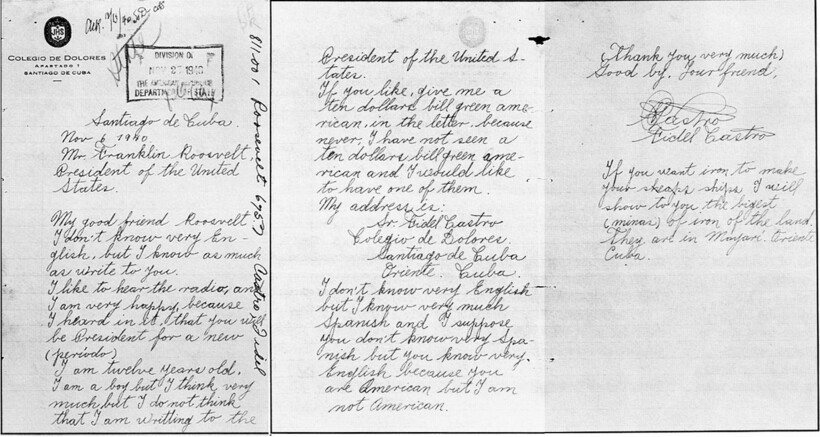

О Фиделе Кастро

Фидель Алехандро (Руз)

Кастро родился в Биране, Куба, 13 августа 1926 года в семье Анхеля Кастро и

Лины Руз в Восточной провинции Кубы. Фидель был третьим ребенком своих братьев

и сестер от отца, Анхеля Кастро. Несмотря на то, что он родился вне брака, он

был привилегированным представителем высшего среднего класса. Он получил

образование в частной школе-интернате, учился в колледже, а затем поступил в

Гарвардскую юридическую школу. В Гарварде он увлекся политическим климатом на

Кубе, особенно в том, что касается национализма, антиимпериализма и социализма.

(Биография Кастро, 2010)

Кастро был женат на

Мирте Диас Баларт. У них был один сын, которого звали Фиделито, что означало

“маленький Фидель”. Ее семья была богатой, и Фидель Кастро воспользовался этой

возможностью, в результате чего стал вести гораздо более богатый образ жизни и

в то же время смог наладить контакты с ключевыми политическими ассоциациями.

Брак распался через шесть лет из-за отсутствия финансовой поддержки у его

семьи. Мирта была его второй женой. (Биография Кастро, 2010)

Энтузиазм Кастро в

отношении реформ и социальной справедливости привел его в Доминиканскую

Республику в попытке помочь свергнуть господина Рафаэля Трухильо. Хотя эта

попытка не увенчалась успехом, это не удержало его от борьбы за социальную

справедливость. Он был членом антикоммунистической партии, которая была создана

с целью разоблачения коррупции в правительстве, разработки стратегий достижения

экономической независимости и осуществления социальных реформ на Кубе.

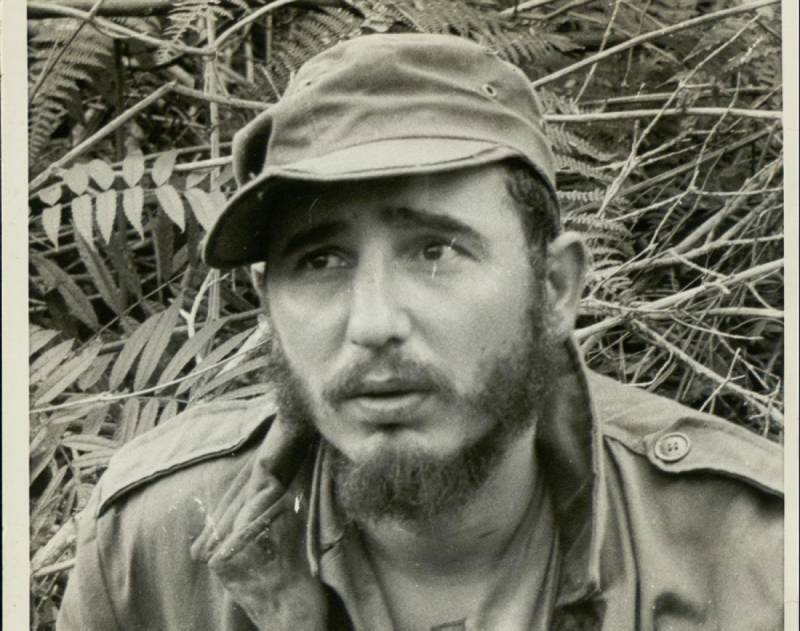

Хотя его попытки

свергнуть тогдашнего лидера генерала Фульхенсио Бартисту провалились, он

никогда не сдавался. Он был приговорен к тюремному заключению за эти попытки

государственного переворота, но продолжал борьбу за то, чтобы стать лидером

Кубы, стремясь осуществить изменения, которые он надеялся осуществить. Эта

долгая борьба была, наконец, реализована 1 января 1959 года, когда он взял на

себя руководство правительством. 15 февраля 1959 года он назначил своего брата

Рауля Кастро командующим вооруженными силами.

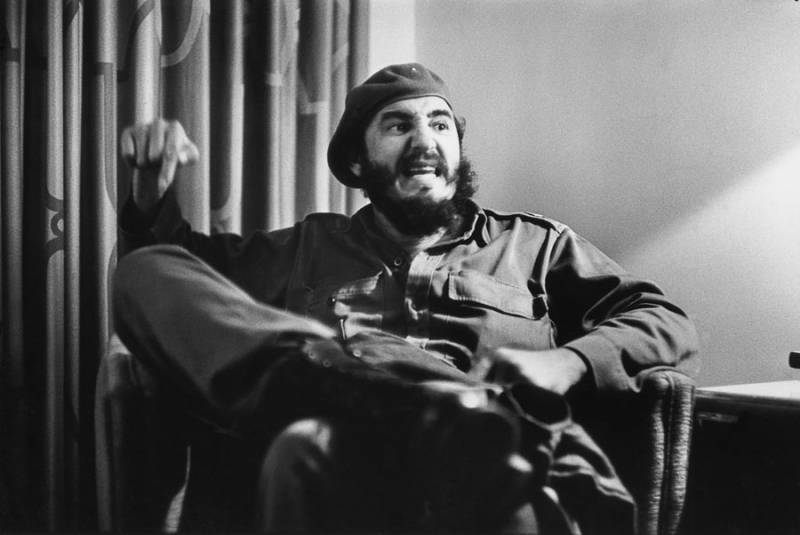

Тип лидера и история

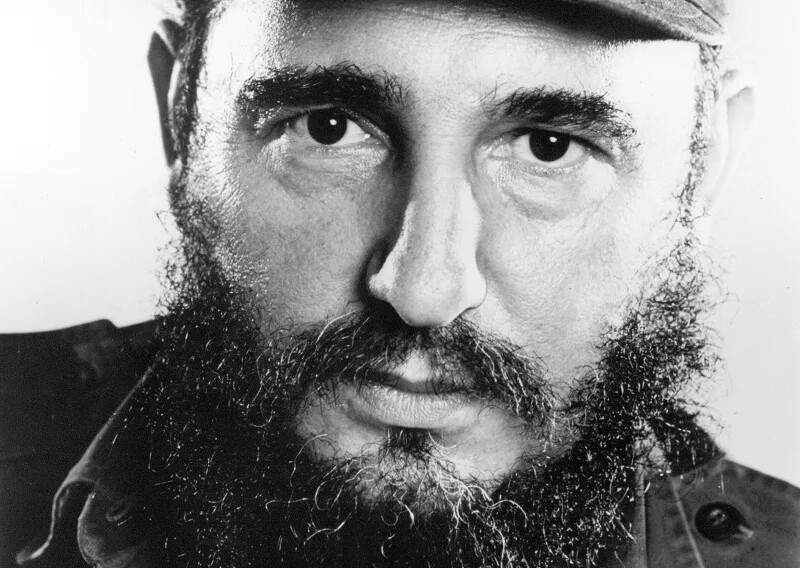

“Харизматичные лидеры

исключительно уверены в себе, сильно мотивированы для достижения и утверждения

влияния и твердо убеждены в моральной правильности своих убеждений” (Хаус и

Адитья, стр. 416). Фидель Кастро — харизматичный и преобразующий лидер.

Нахаванди утверждает, что трансформационное лидерство включает в себя три

фактора, из трех, которые мы определили для определения Кастро; харизма и

интеллектуально развитый характер, которые сами по себе помогли Кастро добиться

радикальных перемен, которые он хотел для Кубы. Это та социальная и

политическая реформа, которую он стремился осуществить как лидер.

Были ли какие-либо

культурные особенности, которые помогли ему в руководстве? Был бы он

эффективным лидером в другом месте?

Культура страны сыграла

важную роль в поведении Фиделя Кастро. Его личность и характер развивались по

мере того, как он присоединялся к группам, и в конце концов они развили свою

собственную культуру. Культурные особенности влияют на то, кого мы считаем

эффективным лидером.

В исследовании

Тромпенаарса о кросс-культурной организационной культуре Кастро вписывается в

категорию семьи, в которой говорится, что они ориентированы на власть,

заботливый лидер; он так глубоко заботился о бедных, что взял силу у богатых,

чтобы дать бедным своей любимой Кубы. Он также был сосредоточен на построении

отношений, но эти отношения не должны перевешиваться внешним источником. Мы

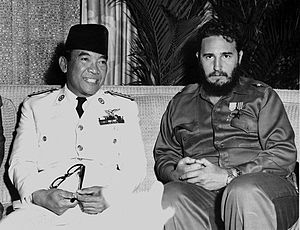

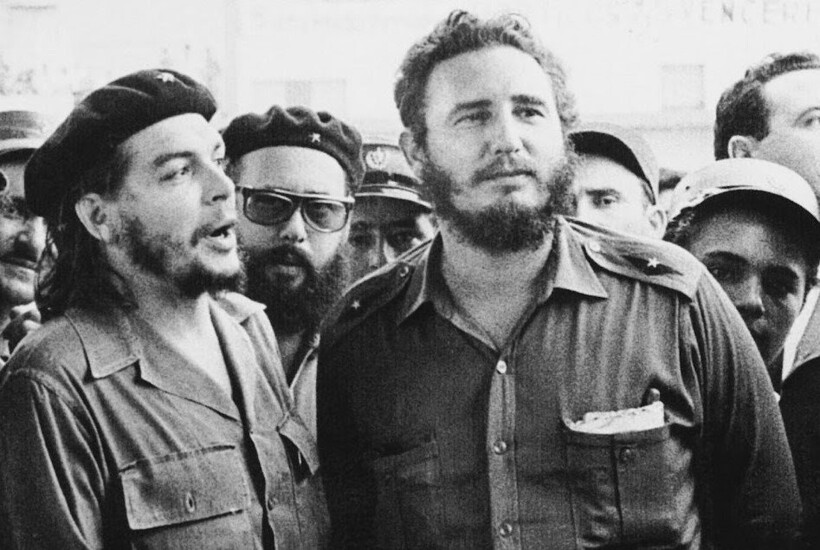

видели, что он установил партнерские отношения с рядом коллег, таких как Че

Гевара из Мексики, Советского Союза, Гренады и Африки. (Биография Кастро, 2010

и Наванди, 2009)

Отражает ли он

какие-либо концепции ранних теорий лидерства?

Кастро проявил

лидерские качества очень рано в детстве. Теория черт характера указывает на то,

что лидерами рождаются, а не становятся. Его качества лидера еще раз

подтвердили этот тезис. Кастро обладал природной способностью влиять на своих

последователей. Он понимал кубинский народ, особенно бедняков. Это оказало

положительное влияние на народ Кубы, особенно зная, что он родился не в бедной

семье и поэтому был для бедных.

Как говорится в тексте

“Теория лидерства эпохи непредвиденных обстоятельств”, точка зрения состоит в

том, что стиль личности, поведение эффективных лидеров зависят от ситуации, в

которой они находятся» (Нахаванди 2009).

Это стало очевидным,

когда Кастро воспользовался возможностью стать освободителем для народа в то

время, когда они были очень недовольны стилем руководства правительства

Бартисты. Он увидел возможность завоевать доверие и последователей и, как

человек, которым он был, в полной мере воспользовался ситуацией. Его подход

оказался успешным. отсюда и причина массового числа последователей. (Биография

Кастро, 2010)

Кастро, благодаря своим

характеристикам, считался лидером, независимо от контекста. Исследования

показывают, что Кастро продемонстрировал стиль принятия решений A2 в нормативной

модели принятия решений. Нахаванди утверждает, что лидеры A2 ищут конкретную

информацию, однако они принимают решения самостоятельно.

Каковы черты и

характеристики, которые делают его лидером?

Как и у всех лидеров, у

него были как положительные, так и отрицательные качества. В ходе исследования

было отмечено, что положительные качества на раннем этапе его пребывания на

посту кубинского лидера перевешивали отрицательные. Его мотивация помогла

кубинцам из низшего класса повысить свой уровень самооценки. Он смог хорошо

управлять страной, несмотря на ограничения, введенные извне, а именно

Соединенными Штатами. В результате он остался верен своим убеждениям и

ценностям. Больше всего он был претендентом; он вдохновлял своих

последователей, брал на себя большие обязанности и проявлял мужество перед

лицом опасности. Стремясь достичь своих целей и задач, он возглавлял все

попытки переворотов. Он никогда не оставлял своих последователей вступать в

сражения войны в одиночку.

С другой стороны, он

был упрямым лидером, который вел за собой железным кулаком. Временами

считалось, что он чересчур самоуверен, и это было главным образом из-за его

образования и опыта. (Нахаванди 2009)

Он был авторитарным

лидером и как таковой не желал мириться с переменами. Это было очевидно в

начале его руководства. Он действительно был склонен к принуждению; он

демонстрировал такое поведение, когда его подчиненные были наказаны за

невыполнение его приказов.

В нашем исследовании мы

определили Кастро как лидера типа А, и Нахаванди утверждает, что характеристики

и поведение, которые сопровождают эти типы лидеров, заключаются в их

потребности контролировать ситуацию. На протяжении всего исследования были

сообщения, в которых говорилось о необходимости Фиделя Кастро получить контроль

над Кубой и стать ее лидером. Его демонстрация плохого делегирования

полномочий, склонность работать в одиночку и трудолюбие — все это

характеристики, которыми он обладает и которые являются характеристиками

лидеров типа А. (Нахаванди 2009)

Г-н Кастро является относительно

средним Макиавелли из-за его эффективности как лидера, и у него была история,

когда он легко манипулировал своими последователями в попытке достичь своих

целей и задач; это состояло в том, чтобы изменить политический климат Кубы,

заботясь о нуждах бедных и завоевывая поддержку благодаря своему посланию и

страсти к своему народу. Тщательный анализ показывает, что на основе показателя

типа Майера Бриггса, где его было немного из всех категорий. Например, как

мыслитель сенсаций, он устанавливал правила и предписания, временами слишком

быстро переходил к действиям и подталкивал других к тому, чтобы перейти к сути.

Остальные не подходят к его характеру. В качестве сенсационного щупальца

наиболее подходящим является нежелание принимать перемены. В категориях

«интуитивный мыслитель» и «чувствующий» эти две категории

применимы к Фиделю Кастро, архитектору прогресса и идей и хорошему

коммуникатору. (Нахаванди 2009)

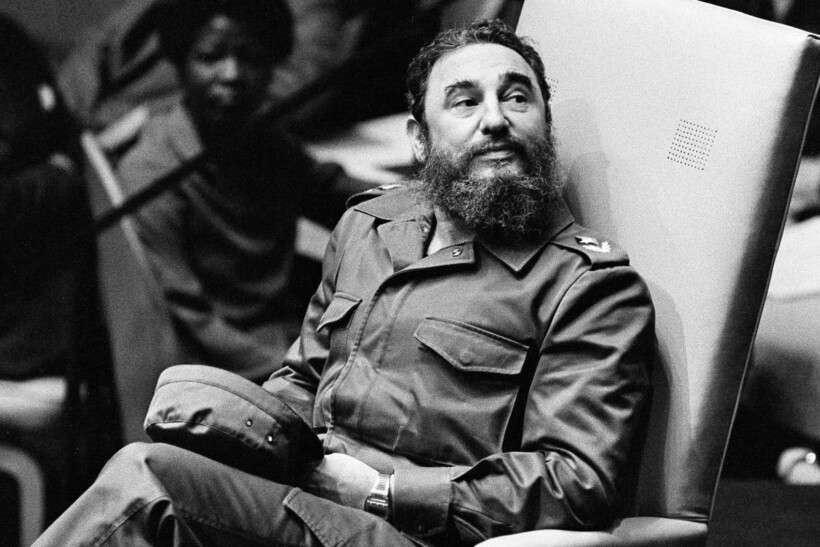

Стиль руководства

Фиделя Кастро

Основываясь на наших

исследованиях, Фидель Кастро продемонстрировал лидерские качества как

харизматичного, так и преобразующего лидера. Он был скорее

диктатором-харизматичным лидером. Он смог собрать своих последователей

благодаря своей харизме, в отличие от того, чтобы собрать их с помощью своей

внешней власти. Фидель всегда заботился о благополучии своего народа, особенно

тех, кому повезло меньше. Таким образом, он отнял богатство и собственность у

более удачливых кубинцев и раздал их менее удачливым. У него было видение

народа Кубы, и поэтому он смог использовать свое видение через народ для

расширения своей власти.

Одним из его видений

было обеспечение того, чтобы у менее удачливых были свои насущные потребности.

Кроме того, он пообещал народу Кубы бесплатное образование, которое он получил.

Делая это, он считал, что очень чутко относится к нуждам своего народа. Хотя

Фидель был харизматичным лидером, он часто демонстрировал диктаторский стиль

руководства. Народу Кубы не была предоставлена свобода слова. При его правлении

народу Кубы не разрешалось покидать Кубу для отдыха в других местах. Люди,

которые не поддерживали его партию, получили выговор и не получили равных

возможностей. Некоторые жители Кубы даже боялись произносить имя Фиделя Кастро.

Вместо этого они делали «знак, дергающий за бороду», чтобы дать

кому-то понять, что они имеют в виду его. Кубинцам также было отказано в

доступе к некоторым пляжам и отелям. Это вызвало оскорбления в адрес народа

Кубы. (Холлидей, 2008).

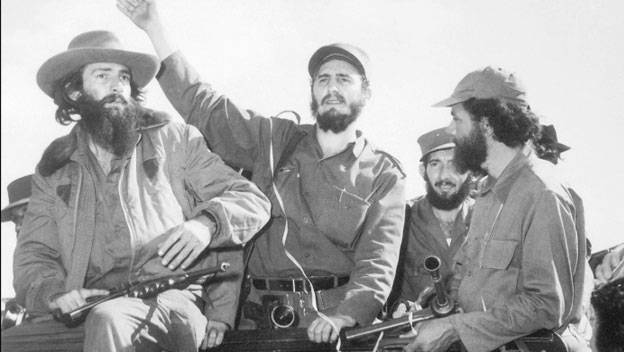

The political career of Fidel Castro saw Cuba undergo significant economic, political, and social changes. In the Cuban Revolution, Fidel Castro and an associated group of revolutionaries toppled the ruling government of Fulgencio Batista,[1] forcing Batista out of power on 1 January 1959. Castro, who had already been an important figure in Cuban society, went on to serve as Prime Minister from 1959 to 1976. He was also the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba, the most senior position in the communist state, from 1961 to 2011. In 1976, Castro officially became President of the Council of State and President of the Council of Ministers. He retained the title until 2008, when the presidency was transferred to his brother, Raúl Castro. Fidel Castro remained the first secretary of the Communist Party until 2011.

Fidel Castro’s government was officially atheist from 1962 until 1992.[2] Cuba attained international prominence under Fidel Castro’s rule, for reasons including his staunch belief in communism, his criticisms of other international figures, and the economic and social changes that were initiated. Castro’s Cuba became a key element within the Cold War struggle between the United States and its allies versus the Soviet Union and its allies. Castro’s desire to take the offensive against capitalism and spread communist revolution ultimately led to the Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias – FAR) fighting in Africa. His aim was to create many Vietnams, reasoning that American troops bogged down throughout the world could not fight any single insurgency effectively. An estimated 7,000–11,000 Cubans died in conflicts in Africa.[3]

Castro died of natural causes in late 2016 at Havana. Castro’s ideas continue to be the primary foundation and manner in which the Cuban government functions to this day.

Premiership (1959–1976)[edit]

Consolidating rule (1959)[edit]

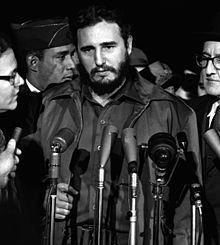

Castro is seen in Washington, D.C., arriving at the MATS Terminal, in April 1959.

On February 16, 1959, Castro was sworn in as Prime Minister of Cuba, and accepted the position on the condition that the Prime Minister’s powers be increased.[4] Between 15 and 26 April Castro visited the U.S. with a delegation of representatives, hired a public relations firm for a charm offensive, and presented himself as a «man of the people». U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower avoided meeting Castro; he was instead met by Vice President Richard Nixon, a man Castro instantly disliked.[5] Proceeding to Canada, Trinidad, Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina, Castro attended an economic conference in Buenos Aires. He unsuccessfully proposed a $30 billion U.S.-funded «Marshall Plan» for the whole region of Latin America.[6]

After appointing himself president of the National Institute of Agrarian Reform (Instituto Nacional de Reforma Agraria — INRA), on 17 May 1959, Castro signed into law the First Agrarian Reform, limiting landholdings to 993 acres (4.02 km2) per owner. He additionally forbade further foreign land-ownership. Large land-holdings (formerly mostly US-owned) were broken up and redistributed; an estimated 200,000 peasants received title deeds. To Castro, this was an important step that broke the control of the well-off landowning class over Cuba’s agriculture. these reforms had widespread support among the Cuban working class.[7] Castro appointed himself president of the National Tourist Industry as well. He introduced unsuccessful measures to encourage African-American tourists to visit, advertising it as a tropical paradise free of racial discrimination.[8] Changes to state wages were implemented; judges and politicians had their pay reduced while low-level civil servants saw theirs raised.[9] In March 1959, Castro ordered rents for those who paid less than $100 a month halved, with measures implemented to increase the Cuban people’s purchasing powers. Productivity decreased, and the country’s financial reserves were drained within only two years.[10] In 1960 the Urban Reform Law was passed, guaranteeing that no household would pay more than 10% of its income in rent.[11] Those who were retired, sick, or below the poverty line paid less than 10% or nothing.[12] Private landlords were abolished as tenants and subtenants gained titles to their residences. These reduced rents were to be paid to the state over a period of 5 to 20 years, after which the renters would become homeowners; the state was supposed to turn over this income to the former landlords as compensation, but there is disagreement as to how often it did. [13] In the 1970s plans to abolish rents altogether were reversed, but nonetheless, by 1972 just 8% of families were paying any rent.[14]

Although he refused to initially categorize his regime as ‘socialist’ and repeatedly denied specifically being a ‘communist’, Castro appointed advocates of Marxism-Leninism to senior government and military positions. Most notably, Che Guevara became Governor of the Central Bank and then Minister of Industries. Appalled, Air Force commander Pedro Luis Díaz Lanz defected to the U.S.[15] Although President Urrutia denounced the defection, he publicly expressed concern with the rising influence of Marxism. Angered, Castro announced his resignation as prime minister, blaming Urrutia for complicating government with his «fevered anti-Communism». Over 500,000 Castro-supporters surrounded the Presidential Palace demanding Urrutia’s resignation, which was duly received. On July 23, Castro resumed his Premiership and appointed the Marxist Osvaldo Dorticós as the new president.[16]

«Until Castro, the U.S. was so overwhelmingly influential in Cuba that the American ambassador was the second most important man, sometimes even more important than the Cuban president.»

— Earl E. T. Smith, former American Ambassador to Cuba, during 1960 testimony to the U.S. Senate[17]

Castro used radio and television to develop a «dialogue with the people», posing questions and making provocative statements.[18] His regime remained popular with workers, peasants and students, who constituted the majority of the country’s population,[19] while opposition came primarily from the middle class. Thousands of doctors, engineers and other professionals emigrated to Florida in the U.S., causing an economic brain drain.[20] Castro’s government cracked down on opponents of his government, and arrested hundreds of counter-revolutionaries.[21] Castro’s government was characterized by the use of psychological torture, subjecting prisoners to solitary confinement, rough treatment, and threatening behavior.[22] Militant anti-Castro groups, funded by exiles, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and Rafael Trujillo’s Dominican government, undertook armed attacks and set up guerrilla bases in Cuba’s mountainous regions. This led to a six-year Escambray Rebellion that lasted longer and involved more soldiers than the revolution. The government won with superior numbers and executed those who surrendered.[23] After conservative editors and journalists expressed hostility towards the government, the pro-Castro printers’ trade union disrupted editorial staff. In January 1960, the government proclaimed that each newspaper would be obliged to publish a «clarification» written by the printers’ union at the end of any articles critical of the government; thus began press censorship in Castro’s Cuba.[24]

Soviet support and U.S. opposition (1960)[edit]

By 1960, the Cold War raged between two superpowers: the United States, a capitalist liberal democracy, and the Soviet Union (USSR), a Marxist-Leninist socialist state ruled by the Communist Party. Expressing contempt for the U.S., Castro shared the ideological views of the USSR, establishing relations with several Marxist-Leninist states.[25] Meeting with Soviet First Deputy Premier Anastas Mikoyan, Castro agreed to provide the USSR with sugar, fruit, fibers, and hides, in return for crude oil, fertilizers, industrial goods, and a $100 million loan.[26] Cuba’s government ordered the country’s refineries – then controlled by the U.S. corporations Shell, Esso and Standard Oil – to process Soviet oil, but under pressure from the U.S. government, they refused. Castro responded by expropriating and nationalizing the refineries. In retaliation, the U.S. cancelled its import of Cuban sugar, provoking Castro to nationalize most U.S.-owned assets on the island, including banks and sugar mills.[27]

Relations between Cuba and the U.S. were further strained following the explosion of a French vessel, the Le Coubre, in Havana harbor in March 1960. The ship carried weapons purchased from Belgium, the cause of the explosion was never determined, but Castro publicly insinuated that the U.S. government were guilty of sabotage. He ended this speech with «¡Patria o Muerte!» («Fatherland or Death»), a proclamation that he made much use of in ensuing years.[28] Inspired by their earlier success with the 1954 Guatemalan coup d’état, on 17 March 1960, U.S. President Eisenhower secretly authorized the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to overthrow Castro’s government. He provided them with a budget of $13 million and permitted them to ally with the Mafia, who were aggrieved that Castro’s government closed down their businesses in Cuba.[29] On 13 October 1960, the U.S. prohibited the majority of exports to Cuba, initiating an economic embargo. In retaliation, INRA took control of 383 private-run businesses on 14 October, and on 25 October a further 166 U.S. companies operating in Cuba had their premises seized and nationalized.[30] On 16 December, the U.S. ended its import quota of Cuban sugar, the country’s primary export.[31]

In September 1960, Castro flew to New York City for the General Assembly of the United Nations. Offended by the attitude of the elite Shelburne Hotel, he and his entourage stayed at the cheap, run-down Hotel Theresa in the impoverished area of Harlem. There he met with journalists and anti-establishment figures like Malcolm X. He also met the Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev and the two leaders publicly highlighted the poverty faced by U.S. citizens in areas like Harlem; Castro described New York as a «city of persecution» against black and poor Americans. Relations between Castro and Khrushchev were warm; they led the applause to one another’s speeches at the General Assembly. Although Castro publicly denied being a socialist, Khrushchev informed his entourage that the Cuban would become «a beacon of Socialism in Latin America.»[32] Subsequently, visited by four other socialists, Polish First Secretary Władysław Gomułka, Bulgarian chairman Todor Zhivkov, Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser and Indian Premier Jawaharlal Nehru,[33] the Fair Play for Cuba Committee organized an evening’s reception for Castro, attended by Allen Ginsberg, Langston Hughes, C. Wright Mills and I. F. Stone.[34]

Castro returned to Cuba on 28 September. He feared a U.S.-backed coup and in 1959 spent $120 million on Soviet, French and Belgian weaponry. Intent on constructing the largest army in Latin America, by early 1960 the government had doubled the size of the Cuban armed forces.[35] Fearing counter-revolutionary elements in the army, the government created a People’s Militia to arm citizens favorable to the revolution, and trained at least 50,000 supporters in combat techniques.[36] In September 1960, they created the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDR), a nationwide civilian organization which implemented neighborhood spying to weed out «counter-revolutionary» activities and could support the army in the case of invasion. They also organized health and education campaigns, and were a conduit for public complaints. Eventually, 80% of Cuba’s population would be involved in the CDR.[37] Castro proclaimed the new administration a direct democracy, in which the Cuban populace could assemble en masse at demonstrations and express their democratic will. As a result, he rejected the need for elections, claiming that representative democratic systems served the interests of socio-economic elites.[38] In contrast, critics condemned the new regime as un-democratic. The U.S. Secretary of State Christian Herter announced that Cuba was adopting the Soviet model of communist rule, with a one-party state, government control of trade unions, suppression of civil liberties and the absence of freedom of speech and press.[39]

Castro’s government emphasised social projects to improve Cuba’s standard of living, often to the detriment of economic development.[40] Major emphasis was placed on education, and under the first 30 months of Castro’s government, more classrooms were opened than in the previous 30 years. The Cuban primary education system offered a work-study program, with half of the time spent in the classroom, and the other half in a productive activity.[41] Health care was nationalized and expanded, with rural health centers and urban polyclinics opening up across the island, offering free medical aid. Universal vaccination against childhood diseases was implemented, and infant mortality rates were reduced dramatically.[40] A third aspect of the social programs was the construction of infrastructure; within the first six months of Castro’s government, 600 miles of road had been built across the island, while $300 million was spent on water and sanitation schemes.[40] Over 800 houses were constructed every month in the early years of the administration in a measure to cut homelessness, while nurseries and day-care centers were opened for children and other centers opened for the disabled and elderly.[40]

Unemployment in Cuba fell significantly over the course of the 1960s and 70s, and a social security bank was founded in early 1959 to assist the unemployed.[42] Seasonal unemployment, previously endemic, was eradicated by overstaffing in the new state farms and migration to urban areas which freed up jobs in the countryside. Many migrants found jobs in new public works projects, the army, trade unions, and security roles.[43]General unemployment was also reduced through greater employment in social services and the bureaucracy, overstaffing in industry, the removal from the ranks of the jobseekers of the young and old through the expansion of education and social security, and the freeing up of jobs through mass emigration.[44] Economist Carmelo Mesa-Lago estimates that from a peak of 13.6% unemployed in 1959, unemployment consistently fell to a level of 1.3% by 1970.[45]

The Bay of Pigs Invasion and embracing socialism (1961–62)[edit]

«There was… no doubts about who the victors were. Cuba’s stature in the world soared to new heights, and Fidel’s role as the adored and revered leader among ordinary Cuban people received a renewed boost. His popularity was greater than ever. In his own mind he had done what generations of Cubans had only fantasized about: he had taken on the United States and won.»

— Peter Bourne, Castro biographer, 1986[46]

In January 1961, Castro ordered Havana’s U.S. Embassy to reduce its 300 staff, suspecting many to be spies. The U.S. responded by ending diplomatic relations, and increasing CIA funding for exiled dissidents; these militants began attacking ships trading with Cuba, and bombed factories, shops, and sugar mills.[47] Both Eisenhower and his successor John F. Kennedy supported a CIA plan to aid a dissident militia, the Democratic Revolutionary Front, to invade Cuba and overthrow Castro; the plan resulted in the Bay of Pigs Invasion in April 1961. On 15 April, CIA-supplied B-26’s bombed three Cuban military airfields; the U.S. announced that the perpetrators were defecting Cuban air force pilots, but Castro exposed these claims as false flag misinformation.[48] Fearing invasion, he ordered the arrest of between 20,000 and 100,000 suspected counter-revolutionaries,[49] publicly proclaiming that «What the imperialists cannot forgive us, is that we have made a Socialist revolution under their noses». This was his first announcement that the government was socialist.[50]

The CIA and Democratic Revolutionary Front had based a 1,400-strong army, Brigade 2506, in Nicaragua. At night, Brigade 2506 landed along Cuba’s Bay of Pigs, and engaged in a firefight with a local revolutionary militia. Castro ordered Captain José Ramón Fernández to launch the counter-offensive, before taking personal control himself. After bombing the invader’s ships and bringing in reinforcements, Castro forced the Brigade’s surrender on 20 April.[51] He ordered the 1189 captured rebels to be interrogated by a panel of journalists on live television, personally taking over questioning on 25 April. 14 were put on trial for crimes allegedly committed before the revolution, while the others were returned to the U.S. in exchange for medicine and food valued at U.S. $25 million.[52] Castro’s victory was a powerful symbol across Latin America, but it also increased internal opposition primarily among the middle-class Cubans who had been detained in the run-up to the invasion. Although most were freed within a few days, many left Cuba for the United States and established themselves in Florida.[53]

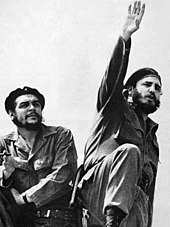

Che Guevara (left) and Castro, photographed by Alberto Korda in 1961.

Consolidating «Socialist Cuba», Castro united the MR-26-7, Popular Socialist Party and Revolutionary Directorate into a governing party based on the Leninist principle of democratic centralism: the Integrated Revolutionary Organizations (Organizaciones Revolucionarias Integradas — ORI), renamed the United Party of the Cuban Socialist Revolution (PURSC) in 1962.[54] Although the USSR was hesitant regarding Castro’s embrace of socialism,[55] relations with the Soviets deepened. Castro sent Fidelito for a Moscow schooling and while the first Soviet technicians arrived in June[56] Castro was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize.[57] In December 1961, Castro proclaimed himself a Marxist-Leninist, and in his Second Declaration of Havana he called on Latin America to rise up in revolution.[58] In response, the U.S. successfully pushed the Organization of American States to expel Cuba; the Soviets privately reprimanded Castro for recklessness, although he received praise from China.[59] Despite their ideological affinity with China, in the Sino-Soviet Split, Cuba allied with the wealthier Soviets, who offered economic and military aid.[60]

The ORI began shaping Cuba using the Soviet model, persecuting political opponents and perceived social deviants such as prostitutes and homosexuals; Castro considered the latter a bourgeois trait.[61] Government officials spoke out against his homophobia, but many gays were forced into the Military Units to Aid Production (Unidades Militares de Ayuda a la Producción — UMAP),[62] something Castro took responsibility for and regretted as a «great injustice» in 2010.[63] By 1962, Cuba’s economy was in steep decline, a result of poor economic management and low productivity coupled with the U.S. trade embargo. Food shortages led to rationing, resulting in protests in Cárdenas.[64] Security reports indicated that many Cubans associated austerity with the «Old Communists» of the PSP, while Castro considered a number of them – namely Aníbal Escalante and Blas Roca – unduly loyal to Moscow. In March 1962 Castro removed the most prominent «Old Communists» from office, labelling them «sectarian».[65] On a personal level, Castro was increasingly lonely, and his relations with Che Guevara became strained as the latter became increasingly anti-Soviet and pro-Chinese.[66]

The Cuban Missile Crisis and furthering socialism (1962–1968)[edit]

U-2 reconnaissance photograph of Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba.

Militarily weaker than NATO, Khrushchev wanted to install Soviet R-12 MRBM nuclear missiles on Cuba to even the power balance.[67] Although conflicted, Castro agreed, believing it would guarantee Cuba’s safety and enhance the cause of socialism.[68] Undertaken in secrecy, only the Castro brothers, Guevara, Dorticós and security chief Ramiro Valdés knew the full plan.[69] Upon discovering it through aerial reconnaissance, in October the U.S. implemented an island-wide quarantine to search vessels headed to Cuba, sparking the Cuban Missile Crisis. The U.S. saw the missiles as offensive, though Castro insisted they were defensive.[70] Castro urged Khrushchev to threaten a nuclear strike on the U.S. should Cuba be attacked, but Khrushchev was desperate to avoid nuclear war.[71] Castro was left out of the negotiations, in which Khrushchev agreed to remove the missiles in exchange for a U.S. commitment not to invade Cuba and an understanding that the U.S. would remove their MRBMs from Turkey and Italy.[72] Feeling betrayed by Khrushchev, Castro was furious and soon fell ill.[73] Proposing a five-point plan, Castro demanded that the U.S. end its embargo, cease supporting dissidents, stop violating Cuban air space and territorial waters and withdraw from Guantanamo Bay Naval Base. Presenting these demands to U Thant, visiting Secretary-General of the United Nations, the U.S. ignored them, and in turn Castro refused to allow the U.N.’s inspection team into Cuba.[74]

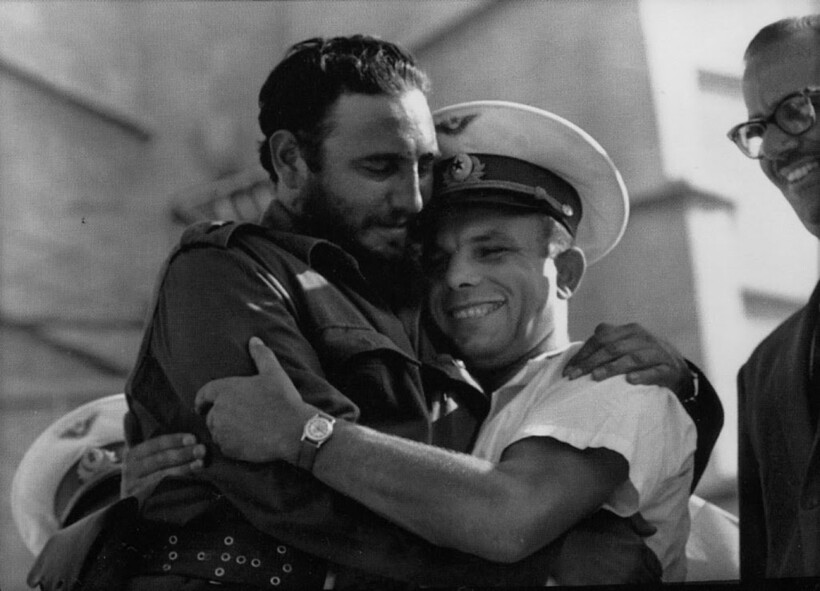

In February 1963, Castro received a personal letter from Khrushchev, inviting him to visit the USSR. Deeply touched, Castro arrived in April and stayed for five weeks. He visited 14 cities, addressed a Red Square rally and watched the May Day parade from the Kremlin, was awarded an honorary doctorate from Moscow State University and became the first foreigner to receive the Order of Lenin.[75][76]

Castro returned to Cuba with new ideas; inspired by Soviet newspaper Pravda, he amalgamated Hoy and Revolución into a new daily, Granma,[77] and oversaw large investment into Cuban sport that resulted in an increased international sporting reputation.[78] The government agreed to temporarily permit emigration for anyone other than males aged between 15 and 26, thereby ridding the government of thousands of opponents.[79] In 1963 his mother died. This was the last time his private life was reported in Cuba’s press.[80] In 1964, Castro returned to Moscow, officially to sign a new five-year sugar trade agreement, but also to discuss the ramifications of the assassination of John F. Kennedy.[81] In October 1965, the Integrated Revolutionary Organizations was officially renamed the «Cuban Communist Party» and published the membership of its Central Committee. Fidel Castro served as First Secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba from 1965 to 2011.[79]

«The greatest threat presented by Castro’s Cuba is as an example to other Latin American states which are beset by poverty, corruption, feudalism, and plutocratic exploitation … his influence in Latin America might be overwhelming and irresistible if, with Soviet help, he could establish in Cuba a Communist utopia.»

— Walter Lippmann, Newsweek, April 27, 1964[82]

Despite Soviet misgivings, Castro continued calling for global revolution and the funding militant leftists. He supported Che Guevara’s «Andean project», an unsuccessful plan to set up a guerrilla movement in the highlands of Bolivia, Peru and Argentina, and allowed revolutionary groups from across the world, from the Viet Cong to the Black Panthers, to train in Cuba.[83][84] He considered western-dominated Africa ripe for revolution, and sent troops and medics to aid Ahmed Ben Bella’s socialist regime in Algeria during the Sand war. He also allied with Alphonse Massemba-Débat’s socialist government in Congo-Brazzaville, and in 1965 Castro authorized Guevara to travel to Congo-Kinshasa to train revolutionaries against the western-backed government.[85][86] Castro was personally devastated when Guevara was subsequently killed by CIA-backed troops in Bolivia in October 1967 and publicly attributed it to Che’s disregard for his own safety.[87][88] In 1966 Castro staged a Tri-Continental Conference of Africa, Asia and Latin America in Havana, further establishing himself as a significant player on the world stage.[89][90] From this conference, Castro created the Latin American Solidarity Organization (OLAS), which adopted the slogan of «The duty of a revolution is to make revolution», signifying that Havana’s leadership of the Latin American revolutionary movement.[91]

Castro’s increasing role on the world stage strained his relationship with the Soviets, now under the leadership of Leonid Brezhnev. Asserting Cuba’s independence, Castro refused to sign the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, declaring it a Soviet-U.S. attempt to dominate the Third World.[92] In turn, Soviet-loyalist Aníbal Escalante began organizing a government network of opposition to Castro, though in January 1968, he and his supporters were arrested for passing state secrets to Moscow.[93] Castro ultimately relented to Brezhnev’s pressure to be obedient, and in August 1968 denounced the Prague Spring as led by a «fascist reactionary rabble» and praised the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia.[94][95][96] Influenced by China’s Great Leap Forward, in 1968 Castro proclaimed a Great Revolutionary Offensive, closed all remaining privately owned shops and businesses and denounced their owners as capitalist counter-revolutionaries.[97]

Economic stagnation and Third World politics (1969–1974)[edit]

In January 1969, Castro publicly celebrated his administration’s tenth anniversary in Revolution Square, using the occasion to ask the assembled crowds if they would tolerate reduced sugar rations, reflecting the country’s economic problems.[97] The majority of the sugar crop was being sent to the USSR, but 1969’s crop was heavily damaged by a hurricane; the government postponed the 1969–70 New Year holidays in order to lengthen the harvest. The military were drafted in, while Castro, and several other Cabinet ministers and foreign diplomats joined in.[98][99] The country nevertheless failed that year’s sugar production quota. Castro publicly offered to resign, but assembled crowds denounced the idea.[100][101] Despite Cuba’s economic problems, many of Castro’s social reforms remained popular, with the population largely supportive of the «Achievements of the Revolution» in education, medical care and road construction, as well as the government’s policy of «direct democracy».[40][101] Cuba turned to the Soviets for economic help, and from 1970 to 1972, Soviet economists re-planned and organized the Cuban economy, founding the Cuban-Soviet Commission of Economic, Scientific and Technical Collaboration, while Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin visited in 1971.[102] In July 1972, Cuba joined the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (Comecon), an economic organization of socialist states, although this further limited Cuba’s economy to agricultural production.[103]

In May 1970, Florida-based dissident group Alpha 66 sank two Cuban fishing boats and captured their crews, demanding the release of Alpha 66 members imprisoned in Cuba. Under U.S. pressure, the hostages were released, and Castro welcomed them back as heroes.[101] In April 1971, Castro gained international condemnation for ordering the arrest of dissident poet Herberto Padilla. When Padilla fell ill, Castro visited him[when?] in hospital. The poet was released after publicly confessing his guilt. Soon after, the government formed the National Cultural Council to ensure that intellectuals and artists supported the administration.[104] In November 1971 he made a state visit to Chile, where socialist President Salvador Allende had been elected as the head of a left-wing coalition. Castro supported Allende’s socialist reforms, where he toured the country to give speeches and press conferences. Suspicious of right-wing elements in the Chilean military, Castro advised Allende to purge these before they led a coup. Castro was proven right; in 1973, Chile’s military led a coup d’état, banned elections, executed thousands and established a military junta led by Commander-in-Chief Augusto Pinochet.[105][106] Castro proceeded to West Africa to meet socialist Guinean President Sékou Touré, where he informed a crowd of Guineans that theirs was Africa’s greatest leader.[107] He then went on a seven-week tour visiting other leftist allies in Africa and Eurasia: Algeria, Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, East Germany, Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union. On every trip he was eager to meet with ordinary people by visiting factories and farms, chatting and joking with them. Although publicly highly supportive of these governments, in private he urged them to do more to aid revolutionary movements in other parts of the world, in particular in the Vietnam War.[108]

In September 1973, he returned to Algiers to attend the Fourth Summit of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM). Various NAM members were critical of Castro’s attendance, claiming that Cuba was aligned to the Warsaw Pact and therefore should not be at the conference, particularly as he praised the Soviet Union in a speech that asserted that it was not imperialistic.[109][110] As the Yom Kippur War broke out in October 1973 between Israel and an Arab coalition led by Egypt and Syria, Castro’s government sent 4,000 troops to prevent Israeli forces from entering Syrian territory.[111] In 1974, Cuba broke off relations with Israel over the treatment of Palestinians during the Israel-Palestine conflict and their increasingly close relationship with the United States. This earned him respect from leaders throughout the Arab world, in particular from the Libyan socialist president Muammar Gaddafi, who became his friend and ally.[112]

That year, Cuba experienced an economic boost, due primarily to the high international price of sugar, but also influenced by new trade credits with Canada, Argentina, and parts of Western Europe.[109][113] Changing economic policy after the 1970 sugar harvest led to higher economic growth in Cuba throughout the 1970s. Estimates of this vary, but a conservative figure came from the World Bank, which put the average annual figure at 4.4% for the period 1971-1980.[114] A number of Latin American states began calling for Cuba’s re-admittance into the Organization of American States (OAS).[115] Cuba’s government called the first National Congress of the Cuban Communist Party, thereby officially announcing Cuba’s status as a socialist state. It adopted a new constitution based on the Soviet model, abolished the position of President and Prime Minister. Castro took the presidency of the newly created Council of State and Council of Ministers, making him both head of state and head of government.[116][117]

Presidency (1976–2008)[edit]

Fidel Castro served as President of the State Council from 1976 to 2008. During this time he participated in many foreign wars including the Angolan Civil War, Mozambique Civil War, Ogaden War; as well as Latin American revolutions. Castro also faced other difficulties as the leader of Cuba, for instance the economic crisis that occurred during the Reagan Era.[citation needed] As well as the deteriorating relationship between the Soviet Union and Cuba due to Glastnost and Perestroika (1980-1989). Beginning in the 1990s Castro led Cuba in an era of economic crisis known as the Special Period. During this decade Castro made many changes to the Cuban economy. Castro reformed Cuban Socialism due to the withdrawal of the Soviet’s backing. Subsequently, Cuba received aid from Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez, in a period known as The Pink Tide era (2000-2006). On July 31, 2006, Castro passed his duties as the President of the State Council to his brother Raúl due to health reasons. Castro renounced his positions as President of the Council of State and Commander and Chief at the February 24 National Assembly meetings in a letter dated February 18, 2008.

Foreign wars and NAM Presidency: (1975–1979)[edit]

«There is often talk of human rights, but it is also necessary to talk of the rights of humanity. Why should some people walk barefoot, so that others can travel in luxurious cars? Why should some live for thirty-five years, so that others can live for seventy years? Why should some be miserably poor, so that others can be hugely rich? I speak on behalf of the children in the world who do not have a piece of bread. I speak on the behalf of the sick who have no medicine, of those whose rights to life and human dignity have been denied.»

— Fidel Castro’s message to the UN General Assembly, 1979[118]

Castro considered Africa to be «the weakest link in the imperialist chain», in November 1975 he ordered 230 military advisors into Southern Africa to aid the Marxist MPLA in the Angolan Civil War. When the U.S. and South Africa stepped up their support of the opposition FLNA and UNITA, Castro ordered a further 18,000 troops to Angola, which played a major role in forcing a South African retreat.[119][120] Traveling to Angola, Castro celebrated with President Agostinho Neto, Guinea’s Ahmed Sékou Touré and Guinea-Bissaun President Luís Cabral, where they agreed to support the Mozambique’s communist government against RENAMO in the Mozambique Civil War.[121] In February, Castro visited Algeria and Libya and spent ten days with Muammar Gaddafi before attending talks with the Marxist government of South Yemen. From there he proceeded to Somalia, Tanzania, Mozambique and Angola where he was greeted by crowds as a hero for Cuba’s role in opposing Apartheid-era South Africa.[122]

In 1977, the Ogaden War broke out as Somalia invaded Ethiopia; although a former ally of Somali President Siad Barre, Castro had warned him against such action, and Cuba sided with Mengistu Haile Mariam’s Marxist government of Ethiopia. He sent troops under the command of General Arnaldo Ochoa to aid the overwhelmed Ethiopian army. After forcing back the Somalis, Mengistu then ordered the Ethiopians to suppress the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front, a measure Castro refused to support.[118][123] Castro extended support to Latin American revolutionary movements, namely the Sandinista National Liberation Front in its overthrow of the Nicaraguan rightist government of Anastasio Somoza Debayle in July 1979.[124] Castro’s critics accused the government of wasting Cuban lives in these military endeavors; the anti-Castro Carthage Foundation-funded Center for a Free Cuba has claimed that an estimated 14,000 Cubans were killed in foreign Cuban military actions.[125][126]

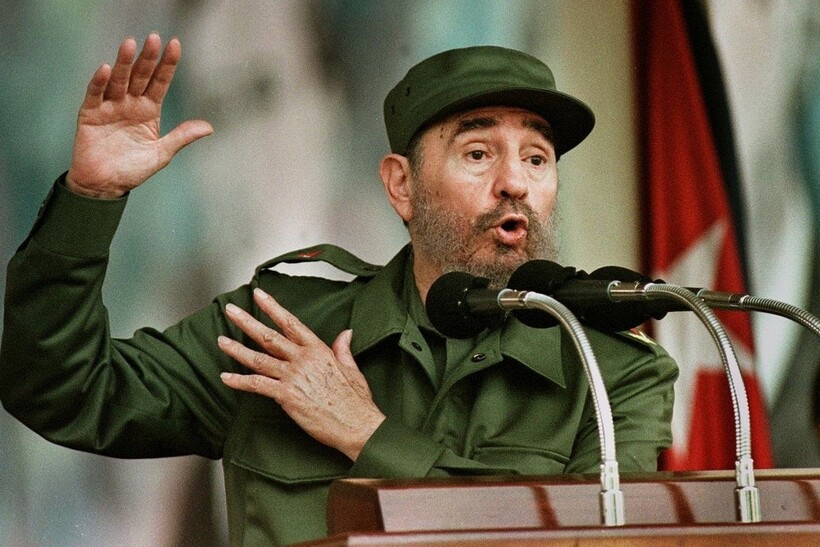

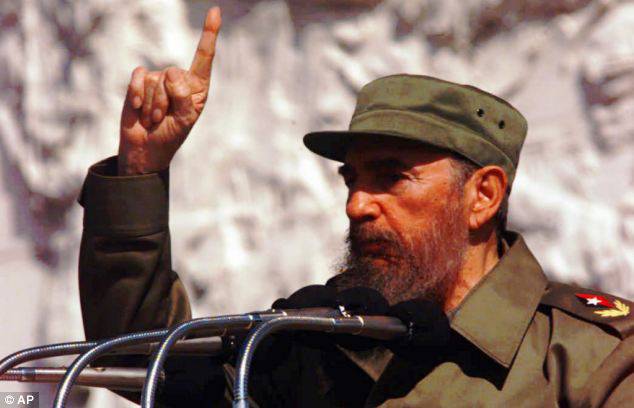

Fidel Castro speaking in Havana, 1978.

In 1979, the Conference of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) was held in Havana, where Castro was selected as NAM president, a position he held till 1982. In his capacity as both President of the NAM and of Cuba he appeared at the United Nations General Assembly in October 1979 and gave a speech on the disparity between the world’s rich and poor. His speech was greeted with much applause from other world leaders,[118][127] though his standing in NAM was damaged by Cuba’s abstinence from the U.N.’s General Assembly condemnation of the Soviet–Afghan War.[127] Cuba’s relations across North America improved under Mexican President Luis Echeverría, Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau,[128] and U.S. President Jimmy Carter. Carter continued criticizing Cuba’s human rights abuses, but adopted a respectful approach which gained Castro’s attention. Considering Carter well-meaning and sincere, Castro freed certain political prisoners and allowed some Cuban exiles to visit relatives on the island, hoping that in turn Carter would abolish the economic embargo and stop CIA support for militant dissidents.[129][130]

Reagan and Gorbachev (1980–1990)[edit]

By the 1980s, Cuba’s economy was again in trouble, following a decline in the market price of sugar and 1979’s decimated harvest.[131][132] Desperate for money, Cuba’s government secretly sold off paintings from national collections and illicitly traded for U.S. electronic goods through Panama.[133] Increasing numbers of Cubans fled to Florida, who were labelled «scum» by Castro.[134] In one incident, 10,000 Cubans stormed the Peruvian Embassy requesting asylum, and so the U.S. agreed that it would accept 3,500 refugees. Castro conceded that those who wanted to leave could do so from Mariel port. Hundreds of boats arrived from the U.S., leading to a mass exodus of 120,000; Castro’s government took advantage of the situation by loading criminals and the mentally ill onto the boats destined for Florida.[135][136] In 1980, Ronald Reagan became U.S. president and then pursued a hard line anti-Castro approach,[137][138] and by 1981, Castro was accusing the U.S. of biological warfare against Cuba.[138]

Although despising Argentina’s right wing military junta, Castro supported them in the 1982 Falklands War against the United Kingdom and offered military aid to the Argentinians.[139] Castro supported the leftist New Jewel Movement that seized power in Grenada in 1979, sent doctors, teachers, and technicians to aid the country’s development, and befriended the Grenadine President Maurice Bishop. When Bishop was murdered in a Soviet-backed coup by hardline Marxist Bernard Coard in October 1983, Castro cautiously continued supporting Grenada’s government. However, the U.S. used the coup as a basis for invading the island. Cuban construction workers died in the conflict, with Castro denouncing the invasion and comparing the U.S. to Nazi Germany.[140][141] Castro feared a U.S. invasion of Nicaragua and sent Arnaldo Ochoa to train the governing Sandinistas in guerrilla warfare, but received little support from the Soviet Union.[142]

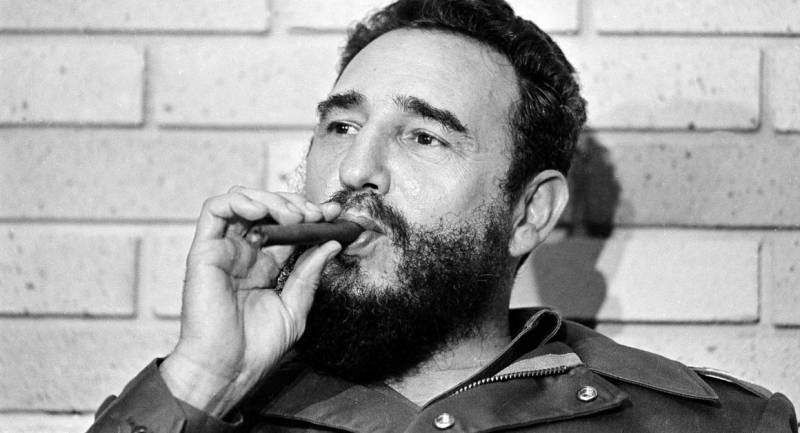

In 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev became General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. A reformer, he implemented measures to increase freedom of the press (glasnost) and economic decentralisation (perestroika) in an attempt to strengthen socialism. Like many orthodox Marxist critics, Castro feared that the reforms would weaken the socialist state and allow capitalist elements to regain control.[143][144] Gorbachev conceded to U.S. demands to reduce support for Cuba,[143] with Cuba–Soviet Union relations deteriorating.[145] When Gorbachev visited Cuba in April 1989, he informed Castro that perestroika meant an end to subsidies for Cuba.[146][147] Ignoring calls for liberalisation in accordance with the Soviet example, Castro continued to clamp down on internal dissidents and in particular kept tabs on the military, the primary threat to the government. A number of senior military officers, including Ochoa and Tony de la Guardia, were investigated for corruption and complicity in cocaine smuggling, tried, and executed in 1989, despite calls for leniency.[148][149] On medical advice given him in October 1985, Castro gave up regularly smoking Cuban cigars, helping to set an example for the rest of the populace.[150] Castro became passionate in his denunciation of the Third World debt problem, arguing that the Third World would never escape the debt that First World banks and governments imposed upon it. In 1985, Havana hosted five international conferences on the world debt problem.[133]

Castro’s image painted onto a now-destroyed lighthouse in Lobito, Angola, 1995.

By November 1987, Castro began spending more time on the Angolan Civil War, in which the Marxists had fallen into retreat. Angolan President José Eduardo dos Santos successfully appealed for more Cuban troops, with Castro later admitting that he devoted more time to Angola than to the domestic situation, believing that a victory would lead to the collapse of apartheid. Gorbachev called for a negotiated end to the conflict and in 1988 organized a quadripartite talks between the USSR, U.S., Cuba and South Africa; they agreed that all foreign troops would pull out of Angola. Castro was angered by Gorbachev’s approach, believing that he was abandoning the plight of the world’s poor in favour of détente.[151][152] In Eastern Europe, socialist governments fell to capitalist reformers between 1989 and 1991 and many western observers expected the same in Cuba.[153][154] Increasingly isolated, Cuba improved relations with Manuel Noriega’s right-wing government in Panama – despite Castro’s personal hatred of Noriega – but it was overthrown in a U.S. invasion in December 1989.[154][155] In February 1990, Castro’s allies in Nicaragua, President Daniel Ortega and the Sandinistas, were defeated by the U.S.-funded National Opposition Union in an election.[154][156] With the collapse of the Eastern Bloc, the U.S. secured a majority vote for a resolution condemning Cuba’s human rights violations at the United Nations Human Rights Commission in Geneva, Switzerland. Cuba asserted that this was a manifestation of U.S. hegemony, and refused to allow an investigative delegation to enter the country.[157]

The Special Period (1991–2000)[edit]

Castro in front of a Havana statue of Cuban national hero José Martí in 2003.

With favourable trade from the Eastern Bloc ended, Castro publicly declared that Cuba was entering a «Special Period in Time of Peace.» Petrol rations were dramatically reduced, Chinese bicycles were imported to replace cars, and factories performing non-essential tasks were shut down. Oxen began to replace tractors, firewood began being used for cooking and electricity cuts were introduced that lasted 16 hours a day. Castro admitted that Cuba faced the worst situation short of open war, and that the country might have to resort to subsistence farming.[158][159] By 1992, the Cuban economy had declined by over 40% in under two years, with major food shortages, widespread malnutrition and a lack of basic goods.[132][160] Castro hoped for a restoration of Marxism–Leninism in the USSR, but refrained from backing the 1991 coup in that country.[161] When Gorbachev regained control, Cuba-Soviet relations deteriorated further and Soviet troops were withdrawn in September 1991.[162] In December, the Soviet Union was officially dismantled as Boris Yeltsin abolished the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and introducing a capitalist multiparty democracy. Yeltsin despised Castro and developed links with the Miami-based Cuban American National Foundation.[161] Castro tried improving relations with the capitalist nations. He welcomed western politicians and investors to Cuba, befriended Manuel Fraga and took a particular interest in Margaret Thatcher’s policies in the U.K., believing that Cuban socialism could learn from her emphasis on low taxation and personal initiative.[163] He ceased support for foreign militants, refrained from praising FARC on a 1994 visit to Colombia and called for a negotiated settlement between the Zapatistas and the Mexican government in 1995. Publicly, he presented himself as a moderate on the world stage.[164]

«We do not have a smidgen of capitalism or neo-liberalism. We are facing a world completely ruled by neo-liberalism and capitalism. This does not mean that we are going to surrender. It means that we have to adopt to the reality of that world. That is what we are doing, with great equanimity, without giving up our ideals, our goals. I ask you to have trust in what the government and party are doing. They are defending, to the last atom, socialist ideas, principles and goals.»

— Fidel Castro explaining the reforms of the Special Period[165]

In 1991, Havana hosted the Pan-American Games, which involved construction of a stadium and accommodation for the athletes; Castro admitted that it was an expensive error, but it was a success for Cuba’s government. Crowds regularly shouted «Fidel! Fidel!» in front of foreign journalists, while Cuba became the first Latin American nation to beat the U.S. to the top of the gold-medal table.[166] Support for Castro remained strong, and although there were small anti-government demonstrations, the Cuban opposition rejected the exile community’s calls for an armed uprising.[167][168] In August 1994, the most serious anti-Castro demonstration in Cuban history occurred in Havana, as 200 to 300 young men began throwing stones at police, demanding that they be allowed to emigrate to Miami. A larger pro-Castro crowd confronted them, and joined by Castro who informed the media that the men were anti-socials misled by U.S. media. The protests dispersed with no recorded injuries.[169][170] Fearing that dissident groups would invade, the government organised the «War of All the People» defence strategy, planning a widespread guerrilla warfare campaign, and the unemployed were given jobs building a network of bunkers and tunnels across the country.[171][172]

Castro recognised the need for reform if Cuban socialism was to survive in a world now dominated by capitalist free markets. In October 1991, the Fourth Congress of the Cuban Communist Party was held in Santiago, at which a number of important changes to the government were announced. Castro would step down as head of government, to be replaced by the much younger Carlos Lage, although Castro would remain the head of the Communist Party and Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces. Many older members of government were to be retired and replaced by their younger counterparts. A number of economic changes were proposed, and subsequently put to a national referendum. Free farmers’ markets and small-scale private enterprises would be legalised in an attempt to stimulate economic growth, while U.S. dollars were also made legal tender. Certain restrictions on emigration were eased, allowing more discontented Cuban citizens to move to the United States. Further democratisation was to be brought in by having the National Assembly’s members elected directly by the people, rather than through municipal and provincial assemblies. Castro welcomed debate between proponents and opponents of the reforms, although over time he began to increasingly sympathise with the opponent’s positions, arguing that such reforms must be delayed.[173][174]

Castro’s government decided to diversify its economy into biotechnology and tourism, the latter outstripping Cuba’s sugar industry as its primary source of revenue in 1995.[175][176] The arrival of thousands of Mexican and Spanish tourists led to increasing numbers of Cubans turning to prostitution; officially illegal, Castro refrained from cracking down on prostitution in Cuba, fearing a political backlash.[177] Economic hardship led many Cubans to turn towards religion, both in the forms of Roman Catholicism and the syncretic faith of Santeria. Although he had long considered religious belief to be backward, Castro softened his approach to the Church and religious institutions He recognised the psychological comfort it could bring, and religious people were permitted for the first time to join the Communist Party.[178][179] Although he viewed the Roman Catholic Church as a reactionary, pro-capitalist institution, Castro decided to organise a visit to Cuba by Pope John Paul II, which took place in January 1998; ultimately, it strengthened the position of both the Church in Cuba, and Castro’s government.[180][181]

In the early 1990s, Castro embraced environmentalism, campaigning against the waste of natural resources and global warming and accused the U.S. of being the world’s primary polluter.[182] His government’s environmentalist policies would prove highly effective; by 2006, Cuba was the only nation in the world which met the WWF’s definition of sustainable development, with an ecological footprint of less than 1.8 hectares per capita and a Human Development Index of over 0.8 for 2007.[183] Similarly, Castro also became a proponent of the anti-globalisation movement. He criticized U.S. global hegemony and the control exerted by multinationals.[182] Castro also maintained his devout anti-apartheid beliefs, and at the July 26 celebrations in 1991, Castro was joined onstage by the South African political activist Nelson Mandela, recently released from prison. Mandela would praise Cuba’s involvement in battling South Africa in Angola and thanked Castro personally.[184][185] He would later attend Mandela’s inauguration as President of South Africa in 1994.[186] In 2001 he attended the Conference Against Racism in South Africa at which he lectured on the global spread of racial stereotypes through U.S. film.[182]

The Pink Tide (2000–2006)[edit]

|

This section needs expansion with: Information on Cuba’s increasingly good relationship with the Pink Tide and its co-founding of ALBA. You can help by adding to it. (October 2012) |

«As I have said before, the ever more sophisticated weapons piling up in the arsenals of the wealthiest and the mightiest can kill the illiterate, the ill, the poor and the hungry but they cannot kill ignorance, illnesses, poverty or hunger.»

— Fidel Castro’s speech at the International Conference on Financing for Development, 2002[187]

Mired in economic problems, Cuba would be aided by the election of socialist and anti-imperialist Hugo Chávez to the Venezuelan Presidency in 1999.[188] In 2000, Castro and Chávez signed an agreement through which Cuba would send 20,000 medics to Venezuela, in return receiving 53,000 barrels of oil per day at preferential rates; in 2004, this trade was stepped up, with Cuba sending 40,000 medics and Venezuela providing 90,000 barrels a day.[189][190] That same year, Castro initiated Mision Milagro, a joint medical project which aimed to provide free eye operations on 300,000 individuals from each nation.[191] The alliance boosted the Cuban economy, and in May 2005 Castro doubled the minimum wage for 1.6 million workers, raised pensions, and delivered new kitchen appliances to Cuba’s poorest residents.[188] Some economic problems remained; in 2004, Castro shut down 118 factories, including steel plants, sugar mills and paper processors to compensate for the crisis of fuel shortages.[192]

Evo Morales of Bolivia has described him as «the grandfather of all Latin American revolutionaries».[193] In contrast to the improved relations between Cuba and a number of leftist Latin American states, in 2004 it broke off diplomatic ties with Panama after centrist President Mireya Moscoso pardoned four Cuban exiles accused of attempting to assassinate Cuban President Fidel Castro in 2000. Diplomatic ties were reinstalled in 2005 following the election of leftist President Martín Torrijos.[194]

Castro’s improving relations across Latin America were accompanied by continuing animosity towards the U.S. However, after massive damage caused by Hurricane Michelle in 2001, Castro successfully proposed a one-time cash purchase of food from the U.S. while declining its government’s offer of humanitarian aid.[195][196] Castro expressed solidarity with the U.S. following the 2001 September 11 attacks, condemning Al Qaeda and offering Cuban airports for the emergency diversion of any U.S. planes. He recognized that the attacks would make U.S. foreign policy more aggressive, which he believed was counter-productive.[197]

Castro amid cheering crowds supporting his presidency in 2005.

At a summit meeting of sixteen Caribbean countries in 1998, Castro called for regional unity, saying that only strengthened cooperation between Caribbean countries would prevent their domination by rich nations in a global economy.[198] Caribbean nations have embraced Cuba’s Fidel Castro while accusing the US of breaking trade promises. Castro, until recently a regional outcast, has been increasing grants and scholarships to the Caribbean countries, while US aid to those has dropped 25% over the past five years.[199] Cuba has opened four additional embassies in the Caribbean Community including: Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, Suriname, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. This development makes Cuba the only country to have embassies in all independent countries of the Caribbean Community.[200]

Castro was known to be a friend of former Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and was an honorary pall bearer at Trudeau’s funeral in October 2000. They had continued their friendship after Trudeau left office until his death. Canada became one of the first American allies openly to trade with Cuba. Cuba still has a good relationship with Canada. On 20 April 1998, Canadian Prime Minister Jean Chrétien arrived in Cuba to meet President Castro and highlight their close ties. He is the first Canadian government leader to visit the island since Pierre Trudeau was in Havana on 16 July 1976.[201]

Stepping down (2006–2008)[edit]

|

This section needs expansion with: Information on Castro’s second presidency of the NAM.. You can help by adding to it. (October 2012) |

On July 31, 2006, Castro delegated all his duties to his brother Raúl; the transfer was described as a temporary measure while Fidel recovered from surgery for an «acute intestinal crisis with sustained bleeding».[202][203][204] Late February 2007, Fidel called into Hugo Chávez’s radio show Aló Presidente,[205] and in April, Chávez told press that Castro was «almost totally recovered».[206] On April 21, Castro met Wu Guanzheng of the Chinese Communist Party’s Politburo,[207] with Chávez visiting in August,[208] and Morales in September.[209] As a comment on Castro’s recovery, U.S. President George W. Bush said: «One day the good Lord will take Fidel Castro away». Hearing about this, the atheist Castro ironically replied: «Now I understand why I survived Bush’s plans and the plans of other presidents who ordered my assassination: the good Lord protected me.» The quote would subsequently be picked up on by the world’s media.[210]

In a letter dated February 18, 2008, Castro announced that he would not accept the positions of President of the Council of State and Commander in Chief at the February 24 National Assembly meetings,[211][212][213] stating that his health was a primary reason for his decision, remarking that «It would betray my conscience to take up a responsibility that requires mobility and total devotion, that I am not in a physical condition to offer».[214] On February 24, 2008, the National Assembly of People’s Power unanimously voted Raúl as president.[215] Describing his brother as «not substitutable», Raúl proposed that Fidel continue to be consulted on matters of great importance, a motion unanimously approved by the 597 National Assembly members.[216]

See also[edit]

- Cuban Revolution

- History of Cuba

- History of land reform in Cuba

- Timeline of Cuban history

- Politics of Cuba

- Foreign relations of Cuba

- Human rights in Cuba

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

Footnotes[edit]

Other[edit]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ Authors, Multiple (2015). Oxford IB Diploma Programme: Authoritarian States Course Companion. Oxford University Press. p. 63.

- ^ «Cuba (09/01)».

- ^ Clodfelter, Micheal (2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492-2015, 4th ed. McFarland. p. 566. ISBN 978-0786474707.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 173; Quirk 1993, p. 228.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 174–177; Quirk 1993, pp. 236–242; Coltman 2003, pp. 155–157.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 177; Quirk 1993, p. 243; Coltman 2003, p. 158.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 177–178; Quirk 1993, p. 280; Coltman 2003, pp. 159–160, «First Agrarian Reform Law (1959)». Archived from the original on October 11, 2007. Retrieved August 29, 2006..

- ^ Quirk 1993, pp. 262–269, 281.

- ^ Quirk 1993, p. 234.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 186.

- ^ Ley de Reforma Urbana 1960 (Cuba) in Stuart Grider, “A Proposal for the Marketization of Housing in Cuba: The Limited Equity Housing Corporation: A New Form of Property,” The University of Miami Inter-American Law Review 27, no. 3 (Spring-Summer 1996): 473, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40176383?seq=21.

- ^ Roberto Veiga, “Informe Central del XXXIV Consejo Nacional de la CTC,” Granma 11, no. 31 (1975): 5 in Carmelo Mesa-Lago, «The Economy of Socialist Cuba», 172.

- ^ Grider, “A Proposal for the Marketization of Housing in Cuba,” 472; Jill Hamberg, Under Construction: Housing Policy in Revolutionary Cuba (New York: Center for Cuban Studies, 1986), 31, note 9.

- ^ Ley de Reforma Urbana 1960 in Grider, “A Proposal for the Marketization of Housing in Cuba,” 472; Banco Nacional de Cuba, Desarrollo y perspectivas de la economía cubana (Havana: Banco Nacional de Cuba, 1975), 104 in Mesa-Lago, Economy of Socialist Cuba, 172; Louis A. Pérez, Cuba: Between Reform and Revolution, 280.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 176–177; Quirk 1993, p. 248; Coltman 2003, pp. 161–166.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 181–183; Quirk 1993, pp. 248–252; Coltman 2003, p. 162.

- ^ Ernesto «Che» Guevara (World Leaders Past & Present), by Douglas Kellner, 1989, Chelsea House Publishers, ISBN 1-55546-835-7, pg 66

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 179.

- ^ Quirk 1993, p. 280; Coltman 2003, p. 168.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 195–197; Coltman 2003, p. 167.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 181, 197; Coltman 2003, p. 168.

- ^ Coltman 2003, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Coltman 2003, p. 167; Ros 2006, pp. 159–201; Franqui 1984, pp. 111–115.

- ^ Quirk 1993, p. 197; Coltman 2003, pp. 165–166.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 202; Quirk 1993, p. 296.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 189–190, 198–199; Quirk 1993, pp. 292–296; Coltman 2003, pp. 170–172.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 205–206; Quirk 1993, pp. 316–319; Coltman 2003, p. 173.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 201–202; Quirk 1993, p. 302; Coltman 2003, p. 172.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 202, 211–213; Quirk 1993, pp. 272–273; Coltman 2003, pp. 172–173.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 214; Quirk 1993, p. 349; Coltman 2003, p. 177.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 215.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 206–209; Quirk 1993, pp. 333–338; Coltman 2003, pp. 174–176.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 209–210; Quirk 1993, p. 337.

- ^ Quirk 1993, p. 339.

- ^ Quirk 1993, p. 300; Coltman 2003, p. 176.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 125; Quirk 1993, p. 300.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 233; Quirk 1993, p. 345; Coltman 2003, p. 176.

- ^ Quirk 1993. p. 313.

- ^ Quirk 1993, p. 330.

- ^ a b c d e Bourne 1986, pp. 275–276.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 275–276; Quirk 1993, p. 324.

- ^ Wyatt MacGaffey and Clifford R. Barnett, Twentieth Century Cuba: The Background of the Castro Revolution, 2nd Ed. (Garden City, New York: Anchor Books, 1965), 207.

- ^ Carmelo Mesa-Lago, The Labor Force, Employment, Unemployment and Underemployment in Cuba: 1899-1970 (Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, 1972), 49.

- ^ Mesa-Lago, Economy of Socialist Cuba, 124.

- ^ Consejo Nacional de Economía, Empleo y desempleo de la fuerza trabajadora (1958); International Labour Organisation, Yearbook of Labour Statistics, 1960, 188; Cuba, Oficina Nacional de los Censos Demográficos y Electoral, Muestro sobre empleo, sub-empleo y desempleo (Havana: Oficina Nacional de los Censos Demográficos y Electoral, 1959-61); Cuba, Dirección Central de Estadística, Boletín Estadístico de Cuba 1966 (Havana: Junta Central de Planificación (JUCEPLAN)), 24 [Note: these statistical annuals, published from 1964-71, will be referred to here as Boletín]; Boletín 1968, 18-22, Boletín 1970, 24; Jorge Risquet, “Comparecencia sobre problemas de la fuerza de trabajo,” Granma (1 August 1970): 2-3; Cuba, Dirección Central de Estadística, Anuario Estadístico de Cuba 1975 (Havana: JUCEPLAN, 1975), 44; Banco Nacional de Cuba, Present Planning and Management System of the National Economy of the Republic of Cuba (Havana: Banco Nacional de Cuba, 1977), 9 and Banco Nacional, Present Planning (1978), 9, (all cited in Mesa-Lago, Economy of Socialist Cuba, 111 and 122 and Mesa-Lago, The Labor Force, 27 and 36).

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 226.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 215–216; Quirk 1993, pp. 353–354, 365–366; Coltman 2003, p. 178.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 217–220; Quirk 1993, pp. 363–367; Coltman 2003, pp. 178–179.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 221–222; Quirk 1993, p. 371.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 221–222; Quirk 1993, p. 369; Coltman 2003, pp. 180, 186.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 222–225; Quirk 1993, pp. 370–374; Coltman 2003, pp. 180–184.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 226–227; Quirk 1993, pp. 375–378; Coltman 2003, pp. 180–184.

- ^ Coltman 2003, pp. 185–186.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 230; Quirk 1993, pp. 387, 396; Coltman 2003, p. 188.

- ^ Quirk 1993, pp. 385–386.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 231, Coltman 2003, p. 188.

- ^ Quirk 1993, p. 405.

- ^ Bourne 1987, pp. 230–234, Quirk, pp. 395, 400–401, Coltman 2003, p. 190.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 232–234, Quirk 1993, pp. 397–401, Coltman 2003, p. 190

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 232, Quirk 1993, p. 397.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 233.

- ^ Coltman 2003, pp. 188–189.

- ^ «Castro admits ‘injustice’ for gays and lesbians during revolution», CNN, Shasta Darlington, August 31, 2010.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 233, Quirk 1993, pp. 203–204, 410–412, Coltman 2003, p. 189.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 234–236, Quirk 1993, pp. 403–406, Coltman 2003, p. 192.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 258–259, Coltman 2003, pp. 191–192.

- ^ Coltman 2003, pp. 192–194.

- ^ Coltman 2003, p. 194.

- ^ Coltman 2003, p. 195.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 238–239, Quirk 1993, p. 425, Coltman 2003, pp. 196–197.

- ^ Coltman 2003, p. 197.

- ^ Coltman 2003, pp. 198–199.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 239, Quirk 1993, pp. 443–434, Coltman 2003, pp. 199–200, 203.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 241–242, Quirk 1993, pp. 444–445.

- ^ Bourne 1986. pp. 245–248.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 204–205.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 249.

- ^ Bourne 1986. pp. 249–250.

- ^ a b Coltman 2003. p. 213.

- ^ Bourne 1986. pp. 250–251.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 263.

- ^ «Cuba Once More», by Walter Lippmann, Newsweek, April 27, 1964, p. 23.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 255.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 211.

- ^ Bourne 1986. pp. 255–256, 260.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 211–212.

- ^ Bourne 1986. pp. 267–268.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 216.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 265.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 214.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 267.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 269.

- ^ Bourne 1986. pp. 269–270.

- ^ Bourne 1986. pp. 270–271.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 216–217.

- ^ Castro, Fidel (August 1968). «Castro comments on Czechoslovakia crisis». FBIS.

- ^ a b Coltman 2003. p. 227.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 273.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 229.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 274.

- ^ a b c Coltman 2003. p. 230.

- ^ Bourne 1986. pp. 276–277.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 277.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 232–233.

- ^ Bourne 1986. pp. 278–280.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 233–236, 240.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 237–238.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 238.

- ^ a b Bourne 1986. pp. 283–284.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 239.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 284.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 239–240.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 240.

- ^ Macrotrends, “Cuba Economic Growth 1970-2022,” accessed May 14, 2022, https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/CUB/cuba/economic-growth-rate.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 282.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 283.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 240–241.

- ^ a b c Coltman 2003. p. 245.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 281, 284–287.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 242–243.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 243.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 243–244.

- ^ Bourne 1986. pp. 291–292.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 249.

- ^ «Recipient Grants: Center for a Free Cuba». August 25, 2006. Archived from the original on August 28, 2007. Retrieved August 25, 2006.

- ^ O’Grady, Mary Anastasia (October 30, 2005). «Counting Castro’s Victims». Wall Street Journal. Center for a Free Cuba. Archived from the original on October 8, 2006. Retrieved May 11, 2006.

- ^ a b Bourne 1986. p. 294.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 244–245.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 289.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 247–248.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 250.

- ^ a b Gott 2004. p. 288.

- ^ a b Coltman 2003. p. 255.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 250–251.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 295.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 251–252.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 296.

- ^ a b Coltman 2003. p. 252.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 253.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 297.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 253–254.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 254–255.

- ^ a b Coltman 2003. p. 256.

- ^ Gott 2004. p. 273.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 257.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 260–261.

- ^ Gott 2004. p. 276.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 258–266.

- ^ Gott 2004. pp. 279–286.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 224.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 257–258.

- ^ Gott 2004. pp. 276–279.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 277.

- ^ a b c Gott 2004. p. 286.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 267–268.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 268–270.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 270–271.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 271.

- ^ Gott 2004. pp. 287–289.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 282.

- ^ a b Coltman 2003. pp. 274–275.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 275.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 290–291.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 305–306.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 291–292.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 272–273.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 275–276.

- ^ Gott 2004. p. 314.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 297–299.

- ^ Gott 2004. pp. 298–299.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 287.

- ^ Gott 2004. pp. 273–274.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 276–281, 284, 287.

- ^ Gott 2004. pp. 291–294.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 288.

- ^ Gott 2004. pp. 290, 322.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 294.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 278, 294–295.

- ^ Gott 2004. p. 309.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 309–311.

- ^ Gott 2004. pp. 306–310.

- ^ a b c Coltman 2003. p. 312.

- ^ «untitled» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-08-21. Retrieved 2016-12-23.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 283.

- ^ Gott 2004. p. 279.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 304.

- ^ «Speech by Fidel Castro to the International Conference on Financing and Development, Monterrey, March 21, 2002». Archived from the original on June 20, 2009. Retrieved December 23, 2016.

- ^ a b Kozloff 2008, p. 24.

- ^ Marcano & Tyszka 2007, pp. 213–215; Kozloff 2008, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Morris, Ruth (18 December 2005). «Cuba’s Doctors Resuscitate Economy Aid Missions Make Money, Not Just Allies». Sun-Sentinel. Archived from the original on 1 October 2007. Retrieved December 28, 2006.

- ^ Kozloff 2008, p. 21.

- ^ «Cuba to shut plants to save power». BBC News. September 30, 2004. Retrieved May 20, 2006.

- ^ «Spiegel interview with Bolivia’s Evo Morales». Der Spiegel. August 28, 2006. Retrieved August 12, 2009.

- ^ Gibbs, Stephen (August 21, 2005). «Cuba and Panama restore relations». BBC News. Retrieved May 21, 2006.

- ^ «Castro welcomes one-off US trade». BBC News. November 17, 2001. Retrieved May 19, 2006.

- ^ «US food arrives in Cuba». BBC News. December 16, 2001. Retrieved May 19, 2006.

- ^ Coltman 2003, p. 320.

- ^ «Castro calls for Caribbean unity». BBC News. August 21, 1998. Retrieved May 21, 2006.

- ^ «Castro finds new friends». BBC News. 25 August 1998. Retrieved May 21, 2006.

- ^ «Cuba opens more Caribbean embassies». Caribbean Net News. March 13, 2006. Retrieved May 11, 2006.

- ^ «Canadian PM visits Fidel in April». BBC News. April 20, 1998. Retrieved May 21, 2006.

- ^ Reaction Mixed to Castro’s Turnover of Power Archived 2014-01-19 at the Wayback Machine. PBS. August 1, 2006

- ^ Castro, Fidel (March 22, 2011). «My Shoes Are Too Tight». Juventud Rebelde. Archived from the original on April 27, 2011. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- ^ «Castro says he resigned as Communist Party chief 5 years ago». CNN. March 22, 2011. Archived from the original on April 15, 2011. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- ^ Pretel, Enrique Andres (February 28, 2007). «Cuba’s Castro says recovering, sounds stronger». Reuters. Retrieved April 28, 2012.

- ^ Pearson, Natalie Obiko (13 April 2007). «Venezuela: Ally Castro Recovering». Associated Press.