Маленькая книга о Lua

Карлу Сегуину — с благодарностью за «маленькую библиотеку».

Введение

Есть прекрасная книга «Программирование на Lua», написанная автором языка. Это настоящий учебник, освещающий все тонкости и особенности языка. Там даже упражнения есть. Будете ли вы её читать просто для ознакомления с еще одним языком программирования? Я думаю, что нет.

Другая крайность — это «Lua за 60 минут». Я видел подобные статьи и не могу однозначно сказать, приносят ли они пользу или причиняют вред. Для меня знакомство с Lua началось именно с этой статьи, но я понял из нее только то, что нуждаюсь в более глубоких источниках, чем прокомментированные сниппеты.

«Маленькие книги» Карла Сегуина настолько точно отвечают на мой запрос, что я набрался смелости присоединиться к жанру. Если моя «маленькая книга» будет хотя бы наполовину настолько хороша, то я сочту задачу выполненной.

Читайте подряд. Последовательность изложения отличается от канонической, зато вам ни разу не встретится раздражающее «вы поймете это потом». Это быстрое чтиво, простое и легкое (надеюсь!), которое поможет понять, стоит ли переходить к более глубокому изучению или уже пора остановиться и больше не тратить время.

Применимость

Применимость — это ответ на вопрос «зачем». Существует совершенно безумное количество языков программирования и у каждого есть свой ответ на этот вопрос. Lua появился в недрах университетской кафедры компьютерной графики как встраиваемый язык для приложений на С.

Описывая Lua, автор называет его расширяемым (то есть умеющим вызывать функции приложения) и расширяющим (то есть умеющим предоставлять свои функции приложению). Будучи сам написан на C, он легко встраивается в C-приложения и взаимодействует с ним. Это совсем не означает, что единственная аудитория языка это программисты на C, но… да, им он полезней всего.

При этом Lua предлагает и самостоятельный интерпретатор, который может использовать внешние динамические библиотеки — как написанные специально для Lua, так и любые другие — с помощью механизма FFI. Во втором случае, правда, дополнительно потребуется библиотека expat или интерпретатор LuaJIT (написанный другим автором, но полностью совместимый с оригинальным Lua), в котором не только реализован FFI, но есть еще и JIT-компиляция, многократно ускоряющий и без того быстрый Lua.

Кстати, о быстродействии. Lua быстр — настолько, что из интерпретаторов с ним могут сравниться лишь Python и JavaScript, а LuaJIT в некоторых задачах их даже опережает (но это спорный момент, поэтому лучше остановимся на «сравним по быстродействию»).

Lua компактен — настолько, что его используют в маршрутизаторах Miktotik, телефонных станциях Asterisk и даже «зашивают» в микросхемы.

И он прост. Его включают в сетевые сканеры nmap и wireshark, он работает внутри баз данных Redis и Tarantool, на нем пишут плагины для медиаплеера Rhythmbox… даже биржевых ботов на платформе Quik. Это немного похоже на «бойцовский клуб» — многие используют Lua, ничего о нем не зная, просто как часть платформы.

Кроме того, на Lua неплохо получаются веб-приложения — благодаря реализованной в проекте OpenResty интеграции c Nginx получаются весьма выносливые к нагрузкам системы. Такие как AliExpress, например. Или CloudFlare.

С легкостью создаются настольные приложения с графическим интерфейсом — с помощью IUP, QT, wxWidgets, FLTK или чего-нибудь еще. Не только под Linux, но и под Windows, MacOS или вообще без графической среды, в «сыром» framebuffer.

Графика, «то, ради чего» Lua писался изначально, открывает дорогу в игровую индустрию. Love2D, специально написанный игровой движок, работает не только в настольных операционных системах, но и на мобильных устройствах. Unity, трехмерный игровой движок, лежит в основе довольно серьезных игровых проектов. Для игр класса AAA, правда, потребуется написать платформу на более «машинном» языке, но внутри MTA, World of Warcraft и S.T.A.L.K.E.R. используется все тот же Lua.

А вот задачи реального времени на Lua делать нельзя, даже если использовать микросхемы NodeMCU. Это интерпретатор для виртуальной машины и доступа к реальному оборудованию у него нет. Не поможет даже написать «подложку» с прямым доступом и управлять ею (в играх так и делается), это будет лишь приближением к желаемому — виртуальная машина асинхронно выполняет свои задачи и вы никогда не сможете выполнить что-то «прямо сейчас». Как бы ни была мала эта задержка, «взрослые» задачи реального времени не для Lua. Оставим это Erlang-у.

Установка

Можно собрать Lua из исходников с сайта lua.org. Это самый суровый путь, но если вы линуксоид, то вам не привыкать. При помощи MinGW, CygWin или Windows Platform SDK вы точно так же можете собрать его и для Windows. Но это необязательно — во многих дистрибутивах Linux бинарные сборки доступны из менеджера пакетов. Для Windows их тоже можно найти и скачать из Интернета. Ну, или установить при помощи Chocolatey — тамошнего аналога пакетного менеджера.

Запуск программ

Если просто запустить интерпретатор — он запустится в интерактивном режиме, где весьма неплох в качестве калькулятора.

$ lua

Lua 5.3.5 Copyright (C) 1994-2018 Lua.org, PUC-Rio

> 2 + 2 * 2

6

В интерактивном режиме можно поэкспериментировать со всеми возможностями языка, но для реального применения лучше все-таки написать программу и передавать имя с файлом программы интерпретатору для выполнения.

$ lua hello.lua

Hello, World!

Содержимое файла hello.lua — каноничная первая программа. Те, кто считает, что первая программа должна быть более осмысленной, упускают самое главное её предназначение — проверить работоспособность установленной среды.

print ("Hello, world!") -- print это функция вывода из стандартной библиотеки

Вы можете использовать Lua в командных файлах Linux, как и любой другой скриптовый язык.

#!/usr/bin/env lua print "Hello, world!" -- для вывода одной строки можно обойтись без скобок

Сохраните эту программу в файл hello.lua, выполните команду chmod +x hello.lua, и вы сможете запускать её прямо из консоли:

$ ./hello.lua

Hello, world!

Комментарии

Самая бесполезная часть программы — текст комментариев для интерпретатора не существует. Но это еще и самый лучший способ объяснить, что происходит, прямо в коде.

-- это короткий комментарий --[[ длинные комментарии нужны не только для долгих "лирических отступлений", но и позволяют временно "отключить" часть кода, не удаляя его ]]

Переменные

Переменные не нужно специально объявлять или каким-то образом инициализировать: при первой записи они создается, при повторных — перезаписывается, по завершении программы — удаляется.

Также нет необходимости определять тип данных, которые будут хранится в переменной — при каждой записи определяется тип сохраняемого значения и выделяется требуемое количество памяти.

Имена переменных могут содержать латинские буквы, цифры (но не могут с них начинаться) и знак подчеркивания. Нет никаких специальных правил — СamelCase, isHungarianNotation, underscore_delimited_names или любой другой способ могут быть использованы без ограничений и в любом сочетании.

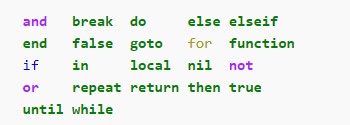

Имена переменных (как и остальные языковые конструкции) регистрозависимы — and является зарезервированным словом и не может использоваться в качестве переменной, а And и AND — могут.

Единственное пожелание автора — не использовать переменные, которые начинаются со знака подчеркивания, за которым следуют заглавные буквы. Внутренние переменные могут совпасть с вашими и программа может повести себя, скажем так, странно.

Выражения

Для записи данных используется операция присваивания. Математически это не равенство, а линейное отображение справа налево. Слева от знака операции должно быть имя переменной, справа — выражение.

4 = a -- это не работает; слева от знака операции только имена переменных

Выражение это способ представления данных при помощи цифр, операций и имен переменных. А значение выражения — это результат его вычисления. Всякий раз, когда интерпретатору встречается выражение, он его вычисляет, а всякий раз, когда встречается присваивание — сохраняет значение в память и связывает с именем переменной.

a = 4 -- теперь у нас есть переменная "a" и в ней содержится число 2 a, b = 4, 8 -- так тоже можно; это называется множественным присваиванием a = 2 + 2 * 2-- значение можно записать как результат математической операции a = b / 2 -- чтение переменных происходит при использовании их в выражениях a, b = b, a -- простой и элегантный способ поменять значения переменных местами i = i + 1 -- просто увеличение значения переменной на 1 x = a = b -- теперь и X, и A равны 4

Когда в переменной пропадает нужда — она уничтожается сборщиком мусора. В общем, все как везде, где произносятся слова «автоматическая сборка мусора»

Пустое значение

Оно всего одно и записывается латинским словом nil, что переводится как «ничего». Это не нуль, не пустая строка и не нулевой указатель. Это ничего. Его не существует.

При чтении несуществующей переменной вы получите nil. При записи в переменную значения nil вы эту переменную уничтожите. А если вы попробуете присвоить nil несуществующей переменной, ничего не произойдет. Вообще.

Логические значения

Их два — true («истина») и false («ложь»).

a, b = true, false -- их можно напрямую присваивать -- они могут быть результатом логических операций x = not b -- true; логическое НЕ x = a and b -- false; логическое И x = a or b -- true; логическое ИЛИ --[[ можно выполнять эти операции и с другими типами данных, логика в этом случае несколько своеобразная, но она есть ]] x = not nil -- true; nil аналогичен false x = not 0 -- false; все остальные значения ведут себя как true, даже 0 x = 4 and 5 -- 5; and возвращает первый аргумент, если он ложный, иначе второй x = 4 or 5 -- 4; or возвращает первый аргумент, если он НЕ ложный, иначе второй x = 3 and 4 or 5 -- 4; это аналог тернарной операции "a?b:c" в Си

Числа

Для хранения чисел Lua использует 64-битные блоки памяти. Это аналогично типу double в С. В версии 5.3 появились целые числа, но это мало что меняет. Единственная разница — вы можете явно создать число с плавающей точкой, если используете десятичную точку, после которой может быть и нуль.

n = 42 -- ответ на Главный вопрос жизни, вселенной и всего такого n = 42.0 -- это значение типа double, а не int n = 0x2A -- он же в шестнадцатиричной системе счисления n = 420e-1 -- в экспоненциальной форме n = 0x2A0p-1 -- или даже в экспоненциальной форме шестнадцатиричного счисления x = 3.1415926 -- у вещественных чисел дробная часть отделяется точкой y = .5 -- нуль перед десятичным разделителем необязателен z = -500 -- как и в случае с отрицательными значениями; фактически это "z = 0 - 500"

Для чисел доступны основные арифметические операции:

a = 2 + 2 -- 4; сложение a = 2 - 2 -- 0; вычитание a = 2 * 2 -- 4; умножение a = 2 ^ 2 -- 4; возведение в степень a = 5 / 2 -- 2.5; деление a = 5 //2 -- 2; целочисленной деление (без дробной части) a = 5 % 2 -- 1; остаток от целочисленного деления a = 2 + 2 * 2 -- 6; приоритеты операций, как в школе a =(2 + 2)* 2 -- 8; но его так же можно менять скобками

А также операции сравнения:

a, b = 3, 4 x = a > b -- false; больше x = a < b -- true; меньше x = a >= b -- false; больше или равно x = a <= b -- true; меньше или равно x = a == b -- false; равно x = a ~= b -- true; не равно

Строки

Строка — это массив байт. Строка может содержать нулевые символы и это не станет признаком конца строки, символы могут быть в любой кодировке или вообще непечатными. В строках можно хранить любые двоичные данные. Между строками в 1 байт и строками в 10 мегабайт нет разницы. И нет ограничений, кроме размера оперативной памяти.

Строки нельзя менять, но можно перезаписывать. То есть нельзя влезть в строку и поменять в ней пятый байт, но можно сформировать такую же строку, но с другим пятым байтом и записать в ту же переменную. Как вы понимаете, это означает копирование строки со всеми накладными расходами этой операции.

s = "Для записи строк используются кавычки" s = 'одиночные кавычки тоже допустимы' s = "можно комбинировать 'одиночные' и "двойные" кавычки в любом сочетании" s = [[А если в тексте много строк, никто не мешает хранить его в строке целиком. Да, при помощи двойных квадратных скобок, как в многострочным комментарии.]] с = #'Hello' -- 5; операция # позволяет узнать длину строки (количество байт, не букв!) s = "строки"..'можно'..[[объединять]] -- это называется "конкатенация" w = [[ Экранирование специальных символов делается как в Си: a - звонок (beep) b - возврат на одну позицию (backspace) r - перевод страницы n - перевод строки (newline) r - возврат каретки (carriage return) t - горизонтальная табуляция v - вертикальная табуляция \ - обратная косая черта (backslash) " - одиночная кавычка ' - двойная кавычка ]] -- строки можно сравнивать x = s == w -- false, строки НЕ равны y = s ~= w -- true, строка НЕ равны

Привидение типов

Если к числу применяются строковые операции, оно превращается в строку. И наоборот, если это возможно.

a = 100..500 -- 100500 a = "10" + 7 -- 17 a = 12 + "a" -- ошибка

Это спорная идея. Лучше использовать явные преобразования и не рисковать.

a = tostring( 10 ) -- "10"; строка b = tonumber("10") -- 10 ; число c = tonumber("XY") -- nil

Таблицы

Используйте таблицы, если вам нужны массивы, словари, структуры, объекты. Таблицы — это всё. Хотя, на самом деле, таблицы это просто способ хранить множество пар «ключ-значение», а все остальное — это то, какие вы выбираете ключи и какие значения.

Если в качестве ключей использовать натуральные числа, то это будет массив.

a = {42,616,999} a[#a + 1] = "Земля-616" -- функция # возвращает количество элементов print (a[4]) --> Земля-616

А еще «натуральные» означает, что нумерация индексов начинается с единицы, а не с нуля. Программистам на C нужно всегда об этом помнить.

Массивы не надо объявлять и под них не выделяется пространство. И индексы у них необязательно последовательные. Можно использовать большие числа и не бояться, что закончится память — в таблице будет только те ключи, которые вы внесли. Если ключи в таблице не являются натуральной последовательностью, то это разряженный массив.

a = {} a[13] = 666 a[100500] = "Alpha Centauri" a[42] = "The Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe, and Everything answer" print(#a) --> 0, для разряженных массивов операция # неприменима

Значения элементов таблицы сами могут быть таблицами. Ограничений на вложенность никаких, таблицы могут быть многомерными матрицами.

a = { {101,102,103}, {201,202,203}, {301,302,303}, -- эта запятая лишняя, но это допустимо } print (a[2][3]) --> 203

Индексы могут быть строковыми. С их помощью можно реализовать ассоциативные массивы (их еще называют словарями).

a = { ["one"] = 1,["two"] = 2,["three"] = 3, four = 4, five = "пять" } print (a.one) --> 1 print (a["four"]) --> 4

Можно заметить, что элементы таблицы определены по-разному и по-разному же вызываются. Вы можете обращаться с таблицей как со словарем, так и как со структурой — это будет все та же таблица.

Фрагменты

У английского «chunk» есть масса смыслов. Если вы во имя точности предпочитаете англицизмы, используйте «чанк» — вполне сложившийся термин (в описании, например, HTTP-протокола). Если нет, то «фрагмент» ничем не хуже. Суть в том, что это просто какое-то количество инструкций языка без начала, конца и какого-то обрамления.

a = 1 print (a) --> 1 a = a + 1 b = a / 2 print (b) --> 1

В программе на Lua не нужно как-то специально оформлять «точку входа», как это делается в C функцией main(). Что касается точки выхода, то её тоже нет — выполнив все инструкции фрагмента, интерпретатор останавливается.

Вы, конечно, можете написать что-то вроде этого:

function main () a = 1 print (a) --> 1 a = a + 1 b = a / 2 print (b) --> 1 end main ()

…но особого смысла в этом нет. Да, сначала объявится функция, но её потом все равно надо будет явным образом вызвать после объявления. И интерпретатору совершенно без разницы, какое у нее имя и надо ли её вообще выполнять.

Полученный код выполняется «как есть», все остальное — на ваше усмотрение.

Блоки и области видимости

Несколько инструкций (тот самый «фрагмент») можно разместить между словами do и end. Это то же самое, что фигурные скобки в C/C++ или begin .. end в Pascal. Блок, группирующий инструкции, является отдельной исполнимой сущностью и применим везде, где применима единичная инструкция.

По умолчанию все переменные глобальные, но при помощи слова local можно явным образом определять переменные, доступные только внутри блока.

a = 1 do local a = 10 print(a) --> 10 b = 2 end print(a) --> 1 print(b) --> 2

Блоки могут быть вложенными. Во внутренних блоках локальные переменные внешних доступны так же, как и глобальные. При создании внутри блока глобальной переменной она будет доступна везде.

Управление потоком

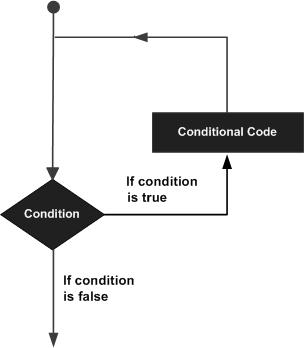

Программа — это набор действий, выполняемых последовательно. В теории автоматов любую программу можно представить в виде графа, где есть начальное, конечное и множество промежуточных состояний, по которым переходит исполнитель, выполняя инструкции. Поток выполнения — это маршрут, которым исполнитель добирается от начальной до конечной точки.

А команды управляющие этим маршрутом называются инструкциями управления потоком. Что позволяет вложить в программу множество маршрутов, которые будут зависеть от разных факторов.

Безусловный переход

Есть разные мнения по поводу инструкции goto, но иногда она действительно полезна. Она имеет неудобный синтаксис и массу ограничений — нельзя «впрыгивать» внутрь блока, «выпрыгивать» из функции и «впрыгивать» внутрь области видимости локальной переменной. Это сделано намеренно — чтобы не возникало желания ею пользоваться без насущной необходимости.

do a = 0 ::loop:: -- имя метки подчиняется тем же правилам, что и имена переменных a = a + 1 -- это не блок, отступы просто для читаемости if a % 2 == 0 then goto continue end if a > 100 then goto exit end -- прыгать внутрь области видимости переменной нельзя print (a) ::continue:: goto loop local b = -a ::exit:: -- но если после метки до конца области видимости ничего нет, то можно end

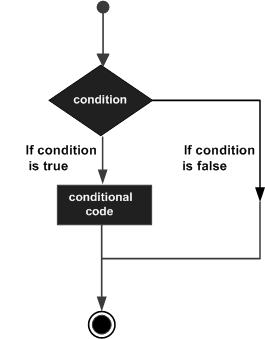

Условия

Программа не всегда должна делать одно и то же.

В зависимости от условий поток выполнения может разделяться на ветки, поэтому условное выполнение называется ветвлением. Каждая ветка может разделяться ещё на ветки и так далее.

if a > 0 then print ("'a' is positive") -- если выполняется уловие end if b > 0 then print ("'b' is positive") else print ("'b' is NOT positive") -- есть не выполняется end if c > 0 then print ("'c' is positive") elseif c < 0 then -- это вместо switch-case, elseif-ов может быть много print ("'c' is negative") else print ("'c' is zero") end

Циклы

Циклы нужны для многократного повторения одинаковых действий.

Цикл с предусловием проверяют условие повторения и выполняют блок, пока оно истинно. Циклы с постусловием сначала выполняют блок, а потом проверяют, достигнуто ли условие завершения.

while false do print ('Hello?') end -- не выполнится ни разу repeat print ('yes, hello!') until true -- выполнится один раз

Цикл с выходом из середины не имеют граничных условий, поэтому в блоке необходимо явным образом предусмотреть выход. При помощи break можно «выпрыгнуть» из цикла, функции и вообще из любого блока. Нет continue, но его можно реализовать с помощью goto.

a = 0 while true do ::continue:: a = a + 2 if a == 13 then -- правильно выбирайте условие выхода из цикла! break end if a % 10 == 0 then goto continue end -- пропускаем всё, кратное 10 print (a) end

В цикле со счётчиком некоторая переменная изменяет своё значение от заданного начального значения до конечного значения с некоторым шагом, и для каждого значения этой переменной блок выполняется один раз.

for i = 0,9,1 do -- если шаг равен 1, третий параметр можно пропустить print(i) end print(i) --> nil; счетчик является локальной переменной и снаружи не доступен

Совместный цикл задает выполнение некоторой операции для объектов из множества.

x = {4, 8, 15, 16, 23, 42} for k,v in ipairs(x) print ('code #'..k..' is '..v) end print(k,v) --> nil nil

Функции

В последнем примере ipairs() это функция. И не просто функция, а итератор. Она получает таблицу и при первом вызове возвращает её первое значение, а при последующих — второй, третье и так далее.

Работает она примерно так:

x = {4, 8, 15, 16, 23, 42} function values(t) local i = 0 return function() i = i + 1 return t[i] -- мы могли бы возвращать еще и i, но ipairs у нас уже есть end end for v in values(x) do -- обратите внимание, что здесь мы тоже обходимся без ключа print (v) end

Этот коротенький пример сразу дает нам массу информации.

Во-первых, функции являются значениями первого класса. То есть их можно присваивать переменным, передавать параметром в другие функции и использовать в качестве возвращаемого значения.

sum = function (a,b) return a + b end print (sum (2,2)) --> 4 function mul (a, b) -- более привычный способ записи всего лишь "семантический сахар" return a*b end print (mul (2,2)) --> 4

Во-вторых, значение не знает имя переменной, в котором оно содержится. Таким образом все функции анонимны. Но не всегда…

function fact(n) if n == 0 then return 1 else return n*fact(n-1) end end

В-третьих, возвращаемых значений может быть несколько. Не один, не два, а столько, сколько захочет вернуть функция. Если при этом мы используем множественное присваивание, то можем получить все значения. Если имен переменных меньше — то «лишние» значения будут отброшены. А если больше — то они получат nil.

Ну, и четвертых, функция является блоком со своей областью видимости для локальных переменных, имея доступ к переменным глобальным. А, будучи объявлена внутри другого блока, локальные переменные внешнего блока воспринимает как глобальные. Это и позволяет нам создавать замыкания — то есть функции, сохраняющие контекст. Весь контекст, без уточнений. Будьте благоразумны и не создавайте лишние сущности.

Кстати, кроме ipairsв стандартной библиотеке Lua есть еще pairs — более общий итератор, который позволяет работать с любыми таблицами, не только с массивами. Но в случае с массивами мы получим значения не по возрастанию ключей, а произвольно.

Сопрограммы

Прежде, чем мы перейдем к сопрограммам (для вас, любители англицизмов, это «корутины»), несколько слов о многозадачности.

Мы уже говорили об графе состояний, исполнителе и потоке выполнения. В многозадачном алгоритме исполнителей несколько и у каждого из них — свое состояние и свой путь в графе состояний. Многопоточные алгоритмы — просто другое название для многозадачных.

Не так важно, выполняются ли потоки разными физическими процессорами или разными потоками одного, переключаются ли они операционной системой, «главным» потоком или явно передают управление друг другу — главное, что каждый поток (строго говоря «нить», от английского «thread» — для англоманов «тред») имеет свое состояние.

В Lua реализована «совместная многопоточность», когда потоки явно уступают выполнение друг другу и сохраняют состояние до следующего момента, когда выполнение столь же явно будет передано им снова. Никакого разделения на физические процессоры или совместного использования процессорного времени. Никакой вытесняющей многозадачности, неблокирующего доступа, семафором, диспетчеров. Только явная передача управление и сохранение состояния. Это логическая многозадачность — на самом деле в любой момент времени выполняется только один поток. Просто их несколько и они переключаются между собой.

c = coroutine.create( function (t) local i = coroutine.yield("initialized") repeat i = coroutine.yield(t[i]) until not t[i] return "finished" end ) print (c,coroutine.status(c)) --> thread: 0x416e52a8 suspended s = {2,3,5,7,11,13,17,19} print (coroutine.resume(c,s)) --> true initialized print (coroutine.resume(c,1)) --> true 2 print (coroutine.resume(c,3)) --> true 5 print (coroutine.resume(c,9)) --> true finished print (c,coroutine.status(c)) --> thread: 0x416e52a8 dead print (coroutine.resume(c,5)) --> false cannot resume dead coroutine

В этом примере описан весь функционал сопрограмм. Давайте разберемся с ним, шаг за шагом.

Вызов corutine.create получает функцию и возвращает спящую («suspended») сопрограмму. Её можно «разбудить» вызовом coroutine.resume и тогда она начинает выполняться.

Выполняется она до тех пор, пока не встретиться вызов coroutine.yield. В этот момент управление возвращается к вызывающему потоку. Следующий вызов coroutine.resume восстановит выполнение сопрограммы, передавая управление ровно в то место, где она была приостановлена.

Сопрограмма может быть вечной — если она время от времени уступает выполнение, то в какой-то момент её можно просто не возобновить. Но она может и завершится и перейти в состояние «dead», возобновить из которого её будет уже невозможно.

Вызовы .resume и .yield могут не только передавать управление, но и обмениваться данными. В примере первый вызов .resume передает сопрограмме таблицу простых чисел, как если бы она передавалась функции в параметре, два других вызова передают данные внутрь сопрограммы, а она, в свою очередь, передает при помощи .yield обратно запрашиваемые значение из таблицы. При попытке получить значение за пределами таблицы сопрограмма заканчивается и возвращает сообщение при помощи return, как самая заурядная функция.

Вот, собственно, и все. Эта простая реализация дает возможность реализовывать многозадачные алгоритмы даже не в многозадачной среде. Впрочем, никто не мешает вам создать на С приложение на с «настоящей» многопоточностью и запустить по виртуальной машине в каждом потоке, предоставив им возможность вызывать специально написанные потокобезопасные функции вашего приложения.

ООП, «которого нет»

Структура с методами это простейший вариант объекта. Метод это функция, сохраненная в элементе таблицы.

a = { name = "Nick", sayHello = function (t) print ("Hello, "..t.name) end } a.sayHello(a) --> Hello, Nick a:sayHello() --> Hello, Nick

Обратите внимание на две последние строчки. Они выполняют одно и то же, но по разному.

Чтобы функция знала, с какой таблицей она работает, ей это надо сообщить. В первом случае таблица явно передается параметром, во втором (когда используется двоеточие вместо точки) имя таблицы неявно передается первым параметром.

Есть несколько способов определять методы.

a = { name = "Nick", whoami = function (t) -- метод можно определить сразу в таблице return t.name end } -- а можно и отдельно от неё function a.hello(t,name) -- здесь таблица передается в явном виде local me = name or t.whoami() print("Hello, "..me) end function a:bye(name) local me = name or self.name -- а здесь появляется "магическая" переменная self print("Goodbye, "..me) end -- способ вызова метода не зависит от того, как он был определен a:hello() --> Hello, Nick a.bye(a) --> Goodbye, Nick a.hello(a,"John") --> Hello, John a:bye("John") --> Goodbye, John print(a:whoami()) --> Nick

Все это тоже семантический сахар.

Метатаблицы

Латинское «meta» буквально означает «после» в том смысле, в каком слово «метафизика» означает «не только физика». Метатаблица способна менять обычное поведение других таблиц.

a,b = {},{} setmetatable (a,b) -- назначаем одну таблицу метатаблицей для другой print (getmetatable (a) == b) --> true b.x = 2 print (a.x) --> 1 print (getmetatable(a).x) --> 2

Что же нам это дает? В описанном примере — практические ничего. Вся сила метатаблиц в метаметодах.

Метаметоды

Это «магические» методы, которые позволяют менять существующее поведение таблицы. «Магические» они потому, что их логика зависит от того, как они называются.

t = { a = 42 } print (t.a) --> 42 print (t.b) --> nil; стандартное поведение таблицы -- создадим метатаблицу с измененной логикой mt = { -- этот метод вызывается при чтении несуществующей переменной __index = function (t,k) return k.." : ключ отсуствует" end } setmetatable (t,mt) -- задаем метатаблицу для нашей таблицы и повторяем те же действия -- теперь таблица ведет себя иначе print (t.a) --> 42 print (t.b) --> b: ключ отсуствует"

Если вы попытаетесь прочесть из таблицы значение по несуществующему ключу, вы получите nil. Но если у таблицы есть метатаблица, а в ней — метод __index, то будет вызван он.

t, mt = {}, {} t.a.b = 42 -- ошибка: t.a равно nil, а не пустая таблица -- определяем новую логику function mt:__index(k) self[k] = {} setmetatable (self[k], mt) return self[k] end setmetatable (t,mt) -- и применяем её к нашей таблице t.a.b.l.e = 42 -- больше никаких проблем с таблицами любой вложенности print (t.a.b.l.e) --> 42

Наследование:

n = {name = "Nick"} j = {name = "John"} m = { __index = m, -- если присвоить этому методу таблицу, поиск ключа будет вестить в ней hello = function (t) print ("Hello, "..t.name) end } setmetatable(n,m) setmetatable(j,m) n:hello() --> ошибка: вы пытаетесь вызвать метод 'hello' (а он равен nil)

Внимание! Это красивый, но неправильный пример.

И дело тут не в том, что __index вместо функции является таблицей (для этого «магического» метода это допустимо). И не в том, что элемент таблицы ссылается на саму таблицу — это тоже нормально. Просто до завершения объявления таблицы она не существует и метод __index не к чему «привязывать».

А вот правильный вариант:

n = {name = "Nick"} j = {name = "John"} m = { -- сначала создаем метатаблицу hello = function (t) print ("Hello, "..t.name) end } m.__index = m -- потом назначаем её setmetatable(n,m) setmetatable(j,m) n:hello() --> Hello, Nick j:hello() --> Hello, John

Здесь мы затрагиваем одну интересную особенность. Пока элемент не определен — он недоступен. Возможно, стоило бы разрешить «ранее связывание», чтобы первый вариант тоже был рабочим. Возможно, это даже будет сделано в будущем, но это уж как решит профессор Иерусалемски — автор и «пожизненный великодушный диктор» Lua.

Впрочем, для функций милостиво сделано исключение.

--[[ специально определяем функцию как переменную, чтобы быть увереным, что тут нет никакого "скрытого сахара" ]] fact = function (n) if n == 1 then return 1 else return n * fact(n-1) -- формально определение функции еще не завершено end end print (fact(5)) --> 120; тем не менее, все работает (но только начиная с версии 5.3)

Не индексом единым…

m = { __index = function (t,k) print ("Чтение "..k) return t[k] end, __nexindex = function (t,k,v) print ("Запись "..k) t[k] = v end } a = {x = 12} setmetatable (a,m) print (a.x) --> 12 a.y = 1 --[[ операция уходит в бесконечный цикл и завершается, когда интерпретатор это понимает]]

(простите, но это был еще один неправильный пример)

Вопреки ожиданиям, программа ведет себя не так, как ожидалось. Это потому, что при обращении к таблице сначала выполняется обращение к элементам, а потом (если их нет) идет поиск «альтернативной логики» в метатаблице (опять же, если она есть).

Если элементы существуют, интерпретатору нет необходимости обращаться к метаметодам. Но мы можем «вынудить» его это делать.

m = { __index = function (t,k) print ("Чтение "..k) return t.data[k] end, __newindex = function (t,k,v) print ("Запись "..k) t.data[k] = v end } a = {data = {}} setmetatable (a,m) a.x = 12 --> Запись x print (a.x) --> Чтение x --> 12 a.y = 1 --> Запись y print (a.z) --> Чтение z --> nil

Мы переносим значения таблицы в таблицу внутри таблицы. Этот прием позволяет перехватывать все операции чтения и записи в таблицу и менять их.

Или не позволять получать элементы, который мы посчитаем закрытыми, как в «классическом» ООП. Хотя на этот счет профессор высказался предельно ясно: «если вам нужны приватные свойства, просто не обращайтесь к ним«.

Арифметические метатметоды

__add: сложение (+)__sub: вычитание (-)__mul: умножение (*)__div: деление (/)__mod: остаток от деления (%)__pow: возведение в степень (^)__unm: унарный (одноместный) минус (-)__idiv: целочисленное деление (//)

В общем случае, если операнды не числа и не строки (которые можно преобразовать в числа), то при выполнении операции будут искаться метаметоды сначала в первом (левом) операнде, а затем во втором (правом). Как только метаметод будет найден, ему передадутся оба операнда, а результат выполнения будет обрезан до одного значения. Иначе будет выдана ошибка.

Обратите внимание на то, что если нужный метаматод будет найдет во втором операнде, они все равно будут переданы в том порядке, в котором записаны в выражении. Эту ситуацию нужно предвидеть и корректно обработать.

Логические метаметоды

__band: битовое И (&)__bor: битовое ИЛИ (|)__bxor: битовое ИЛИ-НЕ (~)__bnot: битовое одноместное НЕ (~)__shl: битовый сдвиг влево (<<)__shr: битовый сдвиг вправо (>>)

Логика схожая.

Строковые метаметоды

__concat: конкатенация (..)__len: длина (#)

Разница в том, что метаметоды будут использоваться, если аргументы не строки и не числа (которые можно привести к строкам). Если в таблице отсутствует реализация __len , то будет вызвана стандартная функция #, а она, как мы помним, не везде применима.

Метаметоды сравнения

__eq: равенство (==)__lt: меньше (<)__le: меньше или равно (<=)

Тут немного веселее. Во-первых, оба операнда должны быть таблицами. Во-вторых, при встрече операций «больше» и «больше или равно», они предварительно будут «перевернуты» в «меньше» и «меньше или равно». В-третьих, результат будет преобразован к логическому типу (то есть к значениям true или false)

Метаметоды доступа

__index: чтение из таблицы__newindex: запись в таблицу нового значения__call: обращение к таблице как к функции__gc: выполняется перед уничтожением таблицы сборщиком мусора

Тут надо заметить, что первые два метода вызываются только при обращении к отсутствующим элементам таблицы. Эти методы получают в параметрах саму таблицу и ключ.

Третий метод очень удобен в качестве «конструктора» — метода по умолчанию. Он получает в параметрах таблицу, за которой следуют все оригинальные аргументы вызова. Ну, а последний метод можно использовать в качестве «деструктора».

Перегрузка операций

Если при выполнении арифметической операции один из операндов является таблицей, то произойдет ошибка. Но с целой «колодой» метаметодов в рукаве мы можем это изменить.

Если один из операндов сложения является таблицей, интерпретатор будет искать метод __sum в его метатаблице. Если оба операнда отвечают этим требованиям — будет использован метаметод первого (левого) операнда.

odd = {1,3,5,7,9} -- таблица нечетных чисел even = {2,4,6,8} -- таблица четных чисел set = { __add = function (a,b) -- передаются операдны операции сложения if type(b) ~= "table" then -- операнд может не быть таблицей a[#a + 1] = b -- тогда просто добавляем его ко множеству else -- в противном случае for _,v in pairs (b) do a[#a + 1] = v -- добавляем по одному все элементы этой таблицы end end return a end } setmetatable(odd,set) -- превращаем таблицы во "множества" setmetatable(even,set) even = even + 10 -- будьте осторожны, ситуацию "even = 10 + even" мы не предусмотрели for _,v in pairs(odd + even) do print(v) -- сумма множеств представляем собой множество всех элементов подмножеств end

Исходя их постулата «таблица это объект» можно реализовать перегрузку всех арифметических и логических операций, чтения и записи, вызова функции… но все это работает только для таблиц — мета-таблицы нельзя назначать никаким другим типам данных. Это сделано специально, чтобы не давать слишком много возможностей «выстрелить себе в ногу».

Стандартная библиотека

В Lua граница между языком и библиотеками очень четкая. Все, что не касается непосредственно языка, вынесено в стандартную библиотеку. Можно собрать Lua без нее и тогда ваша программа не сможет даже вывести на экран строку «привет, мир». Что является огромным преимуществом при использовании Lua внутри другого приложения в качестве встроенного языка, который должен уметь только то, что ему позволено и не оставит скрипту ни малейшего шанса «выбраться из песочницы».

Стандартный библиотек немного и функционал их не впечатляет. Причина в том, что во имя переносимости в стандартных библиотеках есть только то, что может быть реализовано на всех платформах, где есть ANSI C. Все остальные библиотеки так или иначе являются сторонними.

Модули

Принцип повторного использования кода подразумевает, что написанный функционал может быть использован повторно. Примем необязательно автором. Отчуждаемый код — это модули, пакеты, библиотеки, все то, благодаря чему нам не нужно каждый раз писать все самим. Девиз «все уже украдено написано до нас» особенно близок адептам Python-а, но не чужд и нам.

local lunajson = require 'lunajson' -- теперь мы умеет работать с JSON local jsonstr = '{"Hello":["lunajson",1.5]}' local t = lunajson.decode(jsonstr) print(t.Hello[2]) --> 1.5 print(lunajson.encode(t)) --> {"Hello":["lunajson",1.5]}

Разумеется, не все так просто. Для того, чтобы использовать пакет, он должен присутствовать в одном из мест, где его будет искать require.

В переменной package.path содержится строка с вариантами шаблона путей для поиска. Вы можете увидеть из при помощи команды print.

> print (package.path) /usr/share/lua/5.3/?.lua;/usr/share/lua/5.3/?/init.lua;/usr/lib/lua/5.3/?.lua;/usr/lib/lua/5.3/?/init.lua;./?.lua;./?/init.lua

Подставьте вместо вопросительного знака имя модуля — и у вас будет список всех возможных файлов, который будет пытаться открыть команда require.

Это обычная переменная и её можно переопределить или дополнить прямо в программе. И после этого команда require будет исходить их её нового значения.

Проще всего разместить подключаемый модуль в той же директории, что и ваша программа. Создайте файл с именем module.lua и впишите в него следующее:

local complex = { __add = function (x, y) return {a = x.a + y.a, b = x.b + y.b} end, __tostring = function (z) -- этот метаметод вызывается, когда с таблицей пытаются обращаться, как со строкой return z.a..'+'..z.b..'i' end } return function (a, b) z = {a = a, b = b} setmetatable (z, { __index = complex }) return z end

Теперь в своей программе вы можете написать так:

local complex = require "complex" x = complex(3,2) y = complex(4,5) print (x + y) -- вот здесь перед выводом выполняется метатметод __tostring

Пакеты

Имя модуля может содержать точки. При поиске модуля точка превращается в разделитель директории (прямая косая черта для Linux и обратная — для Windows, операционные системы без иерархической файловой системы могут использовать знак подчеркивания). Пакет — это все дерево модулей в одной директории.

Глубина вложенности не важна, дерево пакета может быть довольно разветвленным. Модули пакета являются автономными и связаны только логически.

А если вы снова внимательно посмотрите на значение переменной package.path, то увидите там такую подстроку:

Это позволяет загружать пакет, в модуле init.lua которого будет выполняться загрузка его компонентов или другие действия инициализации.

Заключение

Теперь вы знаете, что такое Lua. Теперь переходите к «Программирование на Lua», той самой книге, о которой мы говорили в самом начале. Если вы решили включить Lua в свой инструментальный набор, эта книга станет для вас настольной. В том числе и потому, что в ней автор рассказывает, что и почему в Lua реализовано именно так, а не иначе.

А еще — там есть такой громадный пласт материала, как встраивание в приложение на C и взаимодействие к кодом, написанным на C. Я посчитал, что для «маленькой книги» это слишком глубокий материал.

Мы также обошли стороной luarocks — это пакетный менеджер, который Hisham Muhammad написал и поддерживает с 2006 года. Это не единственный менеджер пакетов, но для Lua он стал стандартом «де-факто». Строго говоря, он не является частью языка, поэтому я не стал его описывать. Так же, как ZeroBrane Studio, которая является великолепной IDE и удачным примером приложения, полностью написанного на Lua.

Засим откланиваюсь.

Спасибо, что дочитали.

Lua — Overview

Lua is an extensible, lightweight programming language written in C. It started as an in-house project in 1993 by Roberto Ierusalimschy, Luiz Henrique de Figueiredo, and Waldemar Celes.

It was designed from the beginning to be a software that can be integrated with the code written in C and other conventional languages. This integration brings many benefits. It does not try to do what C can already do but aims at offering what C is not good at: a good distance from the hardware, dynamic structures, no redundancies, ease of testing and debugging. For this, Lua has a safe environment, automatic memory management, and good facilities for handling strings and other kinds of data with dynamic size.

Features

Lua provides a set of unique features that makes it distinct from other languages. These include −

- Extensible

- Simple

- Efficient

- Portable

- Free and open

Example Code

print("Hello World!")

How Lua is Implemented?

Lua consists of two parts — the Lua interpreter part and the functioning software system. The functioning software system is an actual computer application that can interpret programs written in the Lua programming language. The Lua interpreter is written in ANSI C, hence it is highly portable and can run on a vast spectrum of devices from high-end network servers to small devices.

Both Lua’s language and its interpreter are mature, small, and fast. It has evolved from other programming languages and top software standards. Being small in size makes it possible for it to run on small devices with low memory.

Learning Lua

The most important point while learning Lua is to focus on the concepts without getting lost in its technical details.

The purpose of learning a programming language is to become a better programmer; that is, to become more effective in designing and implementing new systems and at maintaining old ones.

Some Uses of Lua

-

Game Programming

-

Scripting in Standalone Applications

-

Scripting in Web

-

Extensions and add-ons for databases like MySQL Proxy and MySQL WorkBench

-

Security systems like Intrusion Detection System.

Lua — Environment

Local Environment Setup

If you are still willing to set up your environment for Lua programming language, you need the following softwares available on your computer — (a) Text Editor, (b) The Lua Interpreter, and (c) Lua Compiler.

Text Editor

You need a text editor to type your program. Examples of a few editors include Windows Notepad, OS Edit command, Brief, Epsilon, EMACS, and vim or vi.

Name and version of the text editor can vary on different operating systems. For example, Notepad will be used on Windows, and vim or vi can be used on Windows as well as Linux or UNIX.

The files you create with your editor are called source files and these files contain the program source code. The source files for Lua programs are typically named with the extension «.lua».

The Lua Interpreter

It is just a small program that enables you to type Lua commands and have them executed immediately. It stops the execution of a Lua file in case it encounters an error unlike a compiler that executes fully.

The Lua Compiler

When we extend Lua to other languages/applications, we need a Software Development Kit with a compiler that is compatible with the Lua Application Program Interface.

Installation on Windows

There is a separate IDE named «SciTE» developed for the windows environment, which can be downloaded from https://code.google.com/p/luaforwindows/ download section.

Run the downloaded executable to install the Lua IDE.

Since it’s an IDE, you can both create and build the Lua code using the same.

In case, you are interested in installing Lua in command line mode, you need to install MinGW or Cygwin and then compile and install Lua in windows.

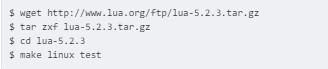

Installation on Linux

To download and build Lua, use the following command −

$ wget http://www.lua.org/ftp/lua-5.2.3.tar.gz $ tar zxf lua-5.2.3.tar.gz $ cd lua-5.2.3 $ make linux test

In order to install on other platforms like aix, ansi, bsd, generic linux, mingw, posix, solaris by replacing Linux in make Linux, test with the corresponding platform name.

We have a helloWorld.lua, in Lua as follows −

print("Hello World!")

Now, we can build and run a Lua file say helloWorld.lua, by switching to the folder containing the file using cd, and then using the following command −

$ lua helloWorld

We can see the following output.

Hello World!

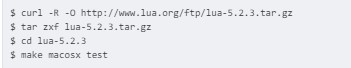

Installation on Mac OS X

To build/test Lua in the Mac OS X, use the following command −

$ curl -R -O http://www.lua.org/ftp/lua-5.2.3.tar.gz $ tar zxf lua-5.2.3.tar.gz $ cd lua-5.2.3 $ make macosx test

In certain cases, you may not have installed the Xcode and command line tools. In such cases, you won’t be able to use the make command. Install Xcode from mac app store. Then go to Preferences of Xcode, and then switch to Downloads and install the component named «Command Line Tools». Once the process is completed, make command will be available to you.

It is not mandatory for you to execute the «make macosx test» statement. Even without executing this command, you can still use Lua in Mac OS X.

We have a helloWorld.lua, in Lua, as follows −

print("Hello World!")

Now, we can build and run a Lua file say helloWorld.lua by switching to the folder containing the file using cd and then using the following command −

$ lua helloWorld

We can see the following output −

Hello World!

Lua IDE

As mentioned earlier, for Windows SciTE, Lua IDE is the default IDE provided by the Lua creator team. The alternate IDE available is from ZeroBrane Studio, which is available across multiple platforms like Windows, Mac and Linux.

There are also plugins for eclipse that enable the Lua development. Using IDE makes it easier for development with features like code completion and is highly recommended. The IDE also provides interactive mode programming similar to the command line version of Lua.

Lua — Basic Syntax

Let us start creating our first Lua program!

First Lua Program

Interactive Mode Programming

Lua provides a mode called interactive mode. In this mode, you can type in instructions one after the other and get instant results. This can be invoked in the shell by using the lua -i or just the lua command. Once you type in this, press Enter and the interactive mode will be started as shown below.

$ lua -i $ Lua 5.1.4 Copyright (C) 1994-2008 Lua.org, PUC-Rio quit to end; cd, dir and edit also available

You can print something using the following statement −

print("test")

Once you press enter, you will get the following output −

test

Default Mode Programming

Invoking the interpreter with a Lua file name parameter begins execution of the file and continues until the script is finished. When the script is finished, the interpreter is no longer active.

Let us write a simple Lua program. All Lua files will have extension .lua. So put the following source code in a test.lua file.

print("test")

Assuming, lua environment is setup correctly, let’s run the program using the following code −

$ lua test.lua

We will get the following output −

test

Let’s try another way to execute a Lua program. Below is the modified test.lua file −

#!/usr/local/bin/lua

print("test")

Here, we have assumed that you have Lua interpreter available in your /usr/local/bin directory. The first line is ignored by the interpreter, if it starts with # sign. Now, try to run this program as follows −

$ chmod a+rx test.lua $./test.lua

We will get the following output.

test

Let us now see the basic structure of Lua program, so that it will be easy for you to understand the basic building blocks of the Lua programming language.

Tokens in Lua

A Lua program consists of various tokens and a token is either a keyword, an identifier, a constant, a string literal, or a symbol. For example, the following Lua statement consists of three tokens −

io.write("Hello world, from ",_VERSION,"!n")

The individual tokens are −

io.write ( "Hello world, from ",_VERSION,"!n" )

Comments

Comments are like helping text in your Lua program and they are ignored by the interpreter. They start with —[[ and terminates with the characters —]] as shown below −

--[[ my first program in Lua --]]

Identifiers

A Lua identifier is a name used to identify a variable, function, or any other user-defined item. An identifier starts with a letter ‘A to Z’ or ‘a to z’ or an underscore ‘_’ followed by zero or more letters, underscores, and digits (0 to 9).

Lua does not allow punctuation characters such as @, $, and % within identifiers. Lua is a case sensitive programming language. Thus Manpower and manpower are two different identifiers in Lua. Here are some examples of the acceptable identifiers −

mohd zara abc move_name a_123 myname50 _temp j a23b9 retVal

Keywords

The following list shows few of the reserved words in Lua. These reserved words may not be used as constants or variables or any other identifier names.

| and | break | do | else |

| elseif | end | false | for |

| function | if | in | local |

| nil | not | or | repeat |

| return | then | true | until |

| while |

Whitespace in Lua

A line containing only whitespace, possibly with a comment, is known as a blank line, and a Lua interpreter totally ignores it.

Whitespace is the term used in Lua to describe blanks, tabs, newline characters and comments. Whitespace separates one part of a statement from another and enables the interpreter to identify where one element in a statement, such as int ends, and the next element begins. Therefore, in the following statement −

local age

There must be at least one whitespace character (usually a space) between local and age for the interpreter to be able to distinguish them. On the other hand, in the following statement −

fruit = apples + oranges --get the total fruit

No whitespace characters are necessary between fruit and =, or between = and apples, although you are free to include some if you wish for readability purpose.

Lua — Variables

A variable is nothing but a name given to a storage area that our programs can manipulate. It can hold different types of values including functions and tables.

The name of a variable can be composed of letters, digits, and the underscore character. It must begin with either a letter or an underscore. Upper and lowercase letters are distinct because Lua is case-sensitive. There are eight basic types of values in Lua −

In Lua, though we don’t have variable data types, we have three types based on the scope of the variable.

-

Global variables − All variables are considered global unless explicitly declared as a local.

-

Local variables − When the type is specified as local for a variable then its scope is limited with the functions inside their scope.

-

Table fields − This is a special type of variable that can hold anything except nil including functions.

Variable Definition in Lua

A variable definition means to tell the interpreter where and how much to create the storage for the variable. A variable definition have an optional type and contains a list of one or more variables of that type as follows −

type variable_list;

Here, type is optionally local or type specified making it global, and variable_list may consist of one or more identifier names separated by commas. Some valid declarations are shown here −

local i, j local i local a,c

The line local i, j both declares and defines the variables i and j; which instructs the interpreter to create variables named i, j and limits the scope to be local.

Variables can be initialized (assigned an initial value) in their declaration. The initializer consists of an equal sign followed by a constant expression as follows −

type variable_list = value_list;

Some examples are −

local d , f = 5 ,10 --declaration of d and f as local variables.

d , f = 5, 10; --declaration of d and f as global variables.

d, f = 10 --[[declaration of d and f as global variables.

Here value of f is nil --]]

For definition without an initializer: variables with static storage duration are implicitly initialized with nil.

Variable Declaration in Lua

As you can see in the above examples, assignments for multiples variables follows a variable_list and value_list format. In the above example local d, f = 5,10 we have d and f in variable_list and 5 and 10 in values list.

Value assigning in Lua takes place like first variable in the variable_list with first value in the value_list and so on. Hence, the value of d is 5 and the value of f is 10.

Example

Try the following example, where variables have been declared at the top, but they have been defined and initialized inside the main function −

-- Variable definition:

local a, b

-- Initialization

a = 10

b = 30

print("value of a:", a)

print("value of b:", b)

-- Swapping of variables

b, a = a, b

print("value of a:", a)

print("value of b:", b)

f = 70.0/3.0

print("value of f", f)

When the above code is built and executed, it produces the following result −

value of a: 10 value of b: 30 value of a: 30 value of b: 10 value of f 23.333333333333

Lvalues and Rvalues in Lua

There are two kinds of expressions in Lua −

-

lvalue − Expressions that refer to a memory location is called «lvalue» expression. An lvalue may appear as either the left-hand or right-hand side of an assignment.

-

rvalue − The term rvalue refers to a data value that is stored at some address in memory. An rvalue is an expression that cannot have a value assigned to it, which means an rvalue may appear on the right-hand side, but not on the left-hand side of an assignment.

Variables are lvalues and so may appear on the left-hand side of an assignment. Numeric literals are rvalues and so may not be assigned and cannot appear on the left-hand side. Following is a valid statement −

g = 20

But following is not a valid statement and would generate a build-time error −

10 = 20

In Lua programming language, apart from the above types of assignment, it is possible to have multiple lvalues and rvalues in the same single statement. It is shown below.

g,l = 20,30

In the above statement, 20 is assigned to g and 30 is assigned to l.

Lua — Data Types

Lua is a dynamically typed language, so the variables don’t have types, only the values have types. Values can be stored in variables, passed as parameters and returned as results.

In Lua, though we don’t have variable data types, but we have types for the values. The list of data types for values are given below.

| Sr.No | Value Type & Description |

|---|---|

| 1 |

nil Used to differentiate the value from having some data or no(nil) data. |

| 2 |

boolean Includes true and false as values. Generally used for condition checking. |

| 3 |

number Represents real(double precision floating point) numbers. |

| 4 |

string Represents array of characters. |

| 5 |

function Represents a method that is written in C or Lua. |

| 6 |

userdata Represents arbitrary C data. |

| 7 |

thread Represents independent threads of execution and it is used to implement coroutines. |

| 8 |

table Represent ordinary arrays, symbol tables, sets, records, graphs, trees, etc., and implements associative arrays. It can hold any value (except nil). |

Type Function

In Lua, there is a function called ‘type’ that enables us to know the type of the variable. Some examples are given in the following code.

print(type("What is my type")) --> string

t = 10

print(type(5.8*t)) --> number

print(type(true)) --> boolean

print(type(print)) --> function

print(type(nil)) --> nil

print(type(type(ABC))) --> string

When you build and execute the above program, it produces the following result on Linux −

string number boolean function nil string

By default, all the variables will point to nil until they are assigned a value or initialized. In Lua, zero and empty strings are considered to be true in case of condition checks. Hence, you have to be careful when using Boolean operations. We will know more using these types in the next chapters.

Lua — Operators

An operator is a symbol that tells the interpreter to perform specific mathematical or logical manipulations. Lua language is rich in built-in operators and provides the following type of operators −

- Arithmetic Operators

- Relational Operators

- Logical Operators

- Misc Operators

This tutorial will explain the arithmetic, relational, logical, and other miscellaneous operators one by one.

Arithmetic Operators

Following table shows all the arithmetic operators supported by Lua language. Assume variable A holds 10 and variable B holds 20 then −

Show Examples

| Operator | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| + | Adds two operands | A + B will give 30 |

| — | Subtracts second operand from the first | A — B will give -10 |

| * | Multiply both operands | A * B will give 200 |

| / | Divide numerator by de-numerator | B / A will give 2 |

| % | Modulus Operator and remainder of after an integer division | B % A will give 0 |

| ^ | Exponent Operator takes the exponents | A^2 will give 100 |

| — | Unary — operator acts as negation | -A will give -10 |

Relational Operators

Following table shows all the relational operators supported by Lua language. Assume variable A holds 10 and variable B holds 20 then −

Show Examples

| Operator | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| == | Checks if the value of two operands are equal or not, if yes then condition becomes true. | (A == B) is not true. |

| ~= | Checks if the value of two operands are equal or not, if values are not equal then condition becomes true. | (A ~= B) is true. |

| > | Checks if the value of left operand is greater than the value of right operand, if yes then condition becomes true. | (A > B) is not true. |

| < | Checks if the value of left operand is less than the value of right operand, if yes then condition becomes true. | (A < B) is true. |

| >= | Checks if the value of left operand is greater than or equal to the value of right operand, if yes then condition becomes true. | (A >= B) is not true. |

| <= | Checks if the value of left operand is less than or equal to the value of right operand, if yes then condition becomes true. | (A <= B) is true. |

Logical Operators

Following table shows all the logical operators supported by Lua language. Assume variable A holds true and variable B holds false then −

Show Examples

| Operator | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| and | Called Logical AND operator. If both the operands are non zero then condition becomes true. | (A and B) is false. |

| or | Called Logical OR Operator. If any of the two operands is non zero then condition becomes true. | (A or B) is true. |

| not | Called Logical NOT Operator. Use to reverses the logical state of its operand. If a condition is true then Logical NOT operator will make false. | !(A and B) is true. |

Misc Operators

Miscellaneous operators supported by Lua Language include concatenation and length.

Show Examples

| Operator | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| .. | Concatenates two strings. | a..b where a is «Hello » and b is «World», will return «Hello World». |

| # | An unary operator that return the length of the a string or a table. | #»Hello» will return 5 |

Operators Precedence in Lua

Operator precedence determines the grouping of terms in an expression. This affects how an expression is evaluated. Certain operators have higher precedence than others; for example, the multiplication operator has higher precedence than the addition operator −

For example, x = 7 + 3 * 2; Here x is assigned 13, not 20 because operator * has higher precedence than + so it first get multiplied with 3*2 and then adds into 7.

Here, operators with the highest precedence appear at the top of the table, those with the lowest appear at the bottom. Within an expression, higher precedence operators will be evaluated first.

Show Examples

| Category | Operator | Associativity |

|---|---|---|

| Unary | not # — | Right to left |

| Concatenation | .. | Right to left |

| Multiplicative | * / % | Left to right |

| Additive | + — | Left to right |

| Relational | < > <= >= == ~= | Left to right |

| Equality | == ~= | Left to right |

| Logical AND | and | Left to right |

| Logical OR | or | Left to right |

Lua — Loops

There may be a situation when you need to execute a block of code several number of times. In general, statements are executed sequentially: the first statement in a function is executed first, followed by the second, and so on.

Programming languages provide various control structures that allow for more complicated execution paths.

A loop statement allows us to execute a statement or group of statements multiple times. Following is the general form of a loop statement in most of the programming languages −

Lua provides the following types of loops to handle looping requirements.

| Sr.No. | Loop Type & Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | while loop

Repeats a statement or group of statements while a given condition is true. It tests the condition before executing the loop body. |

| 2 | for loop

Executes a sequence of statements multiple times and abbreviates the code that manages the loop variable. |

| 3 | repeat…until loop

Repeats the operation of group of statements till the until condition is met. |

| 4 | nested loops

You can use one or more loop inside any another while, for or do..while loop. |

Loop Control Statement

Loop control statement changes execution from its normal sequence. When execution leaves a scope, all automatic objects that were created in that scope are destroyed.

Lua supports the following control statements.

| Sr.No. | Control Statement & Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | break statement

Terminates the loop and transfers execution to the statement immediately following the loop or switch. |

The Infinite Loop

A loop becomes infinite loop if a condition never becomes false. The while loop is often used for this purpose. Since we directly give true for the condition, it keeps executing forever. We can use the break statement to break this loop.

while( true )

do

print("This loop will run forever.")

end

Lua — Decision Making

Decision making structures require that the programmer specifies one or more conditions to be evaluated or tested by the program, along with a statement or statements to be executed, if the condition is determined to be true, and optionally, other statements to be executed if the condition is determined to be false.

Following is the general form of a typical decision making structure found in most of the programming languages −

Lua programming language assumes any combination of Boolean true and non-nil values as true, and if it is either boolean false or nil, then it is assumed as false value. It is to be noted that in Lua, zero will be considered as true.

Lua programming language provides the following types of decision making statements.

| Sr.No. | Statement & Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | if statement

An if statement consists of a boolean expression followed by one or more statements. |

| 2 | if…else statement

An if statement can be followed by an optional else statement, which executes when the boolean expression is false. |

| 3 | nested if statements

You can use one if or else if statement inside another if or else if statement(s). |

Lua — Functions

A function is a group of statements that together perform a task. You can divide up your code into separate functions. How you divide up your code among different functions is up to you, but logically the division usually unique, is so each function performs a specific task.

The Lua language provides numerous built-in methods that your program can call. For example, method print() to print the argument passed as input in console.

A function is known with various names like a method or a sub-routine or a procedure etc.

Defining a Function

The general form of a method definition in Lua programming language is as follows −

optional_function_scope function function_name( argument1, argument2, argument3........, argumentn) function_body return result_params_comma_separated end

A method definition in Lua programming language consists of a method header and a method body. Here are all the parts of a method −

-

Optional Function Scope − You can use keyword local to limit the scope of the function or ignore the scope section, which will make it a global function.

-

Function Name − This is the actual name of the function. The function name and the parameter list together constitute the function signature.

-

Arguments − An argument is like a placeholder. When a function is invoked, you pass a value to the argument. This value is referred to as the actual parameter or argument. The parameter list refers to the type, order, and number of the arguments of a method. Arguments are optional; that is, a method may contain no argument.

-

Function Body − The method body contains a collection of statements that define what the method does.

-

Return − In Lua, it is possible to return multiple values by following the return keyword with the comma separated return values.

Example

Following is the source code for a function called max(). This function takes two parameters num1 and num2 and returns the maximum between the two −

--[[ function returning the max between two numbers --]]

function max(num1, num2)

if (num1 > num2) then

result = num1;

else

result = num2;

end

return result;

end

Function Arguments

If a function is to use arguments, it must declare the variables that accept the values of the arguments. These variables are called the formal parameters of the function.

The formal parameters behave like other local variables inside the function and are created upon entry into the function and destroyed upon exit.

Calling a Function

While creating a Lua function, you give a definition of what the function has to do. To use a method, you will have to call that function to perform the defined task.

When a program calls a function, program control is transferred to the called function. A called function performs the defined task and when its return statement is executed or when its function’s end is reached, it returns program control back to the main program.

To call a method, you simply need to pass the required parameters along with the method name and if the method returns a value, then you can store the returned value. For example −

function max(num1, num2)

if (num1 > num2) then

result = num1;

else

result = num2;

end

return result;

end

-- calling a function

print("The maximum of the two numbers is ",max(10,4))

print("The maximum of the two numbers is ",max(5,6))

When we run the above code, we will get the following output.

The maximum of the two numbers is 10 The maximum of the two numbers is 6

Assigning and Passing Functions

In Lua, we can assign the function to variables and also can pass them as parameters of another function. Here is a simple example for assigning and passing a function as parameter in Lua.

myprint = function(param)

print("This is my print function - ##",param,"##")

end

function add(num1,num2,functionPrint)

result = num1 + num2

functionPrint(result)

end

myprint(10)

add(2,5,myprint)

When we run the above code, we will get the following output.

This is my print function - ## 10 ## This is my print function - ## 7 ##

Function with Variable Argument

It is possible to create functions with variable arguments in Lua using ‘…’ as its parameter. We can get a grasp of this by seeing an example in which the function will return the average and it can take variable arguments.

function average(...)

result = 0

local arg = {...}

for i,v in ipairs(arg) do

result = result + v

end

return result/#arg

end

print("The average is",average(10,5,3,4,5,6))

When we run the above code, we will get the following output.

The average is 5.5

Lua — Strings

String is a sequence of characters as well as control characters like form feed. String can be initialized with three forms which includes −

- Characters between single quotes

- Characters between double quotes

- Characters between [[ and ]]

An example for the above three forms are shown below.

string1 = "Lua"

print(""String 1 is"",string1)

string2 = 'Tutorial'

print("String 2 is",string2)

string3 = [["Lua Tutorial"]]

print("String 3 is",string3)

When we run the above program, we will get the following output.

"String 1 is" Lua String 2 is Tutorial String 3 is "Lua Tutorial"

Escape sequence characters are used in string to change the normal interpretation of characters. For example, to print double inverted commas («»), we have used » in the above example. The escape sequence and its use is listed below in the table.

| Escape Sequence | Use |

|---|---|

| a | Bell |

| b | Backspace |

| f | Formfeed |

| n | New line |

| r | Carriage return |

| t | Tab |

| v | Vertical tab |

| \ | Backslash |

| « | Double quotes |

| ‘ | Single quotes |

| [ | Left square bracket |

| ] | Right square bracket |

String Manipulation

Lua supports string to manipulate strings −

| Sr.No. | Method & Purpose |

|---|---|

| 1 |

string.upper(argument) Returns a capitalized representation of the argument. |

| 2 |

string.lower(argument) Returns a lower case representation of the argument. |

| 3 |

string.gsub(mainString,findString,replaceString) Returns a string by replacing occurrences of findString with replaceString. |

| 4 |

string.find(mainString,findString, optionalStartIndex,optionalEndIndex) Returns the start index and end index of the findString in the main string and nil if not found. |

| 5 |

string.reverse(arg) Returns a string by reversing the characters of the passed string. |

| 6 |

string.format(…) Returns a formatted string. |

| 7 |

string.char(arg) and string.byte(arg) Returns internal numeric and character representations of input argument. |

| 8 |

string.len(arg) Returns a length of the passed string. |

| 9 |

string.rep(string, n)) Returns a string by repeating the same string n number times. |

| 10 |

.. Thus operator concatenates two strings. |

Now, let’s dive into a few examples to exactly see how these string manipulation functions behave.

Case Manipulation

A sample code for manipulating the strings to upper and lower case is given below.

string1 = "Lua"; print(string.upper(string1)) print(string.lower(string1))

When we run the above program, we will get the following output.

LUA lua

Replacing a Substring

A sample code for replacing occurrences of one string with another is given below.

string = "Lua Tutorial"

-- replacing strings

newstring = string.gsub(string,"Tutorial","Language")

print("The new string is "..newstring)

When we run the above program, we will get the following output.

The new string is Lua Language

Finding and Reversing

A sample code for finding the index of substring and reversing string is given below.

string = "Lua Tutorial"

-- replacing strings

print(string.find(string,"Tutorial"))

reversedString = string.reverse(string)

print("The new string is",reversedString)

When we run the above program, we will get the following output.

5 12 The new string is lairotuT auL

Formatting Strings

Many times in our programming, we may need to print strings in a formatted way. You can use the string.format function to format the output as shown below.

string1 = "Lua"

string2 = "Tutorial"

number1 = 10

number2 = 20

-- Basic string formatting

print(string.format("Basic formatting %s %s",string1,string2))

-- Date formatting

date = 2; month = 1; year = 2014

print(string.format("Date formatting %02d/%02d/%03d", date, month, year))

-- Decimal formatting

print(string.format("%.4f",1/3))

When we run the above program, we will get the following output.

Basic formatting Lua Tutorial Date formatting 02/01/2014 0.3333

Character and Byte Representations

A sample code for character and byte representation, which is used for converting the string from string to internal representation and vice versa.

-- Byte conversion

-- First character

print(string.byte("Lua"))

-- Third character

print(string.byte("Lua",3))

-- first character from last

print(string.byte("Lua",-1))

-- Second character

print(string.byte("Lua",2))

-- Second character from last

print(string.byte("Lua",-2))

-- Internal Numeric ASCII Conversion

print(string.char(97))

When we run the above program, we will get the following output.

76 97 97 117 117 a

Other Common Functions

The common string manipulations include string concatenation, finding length of string and at times repeating the same string multiple times. The example for these operations is given below.

string1 = "Lua"

string2 = "Tutorial"

-- String Concatenations using ..

print("Concatenated string",string1..string2)

-- Length of string

print("Length of string1 is ",string.len(string1))

-- Repeating strings

repeatedString = string.rep(string1,3)

print(repeatedString)

When we run the above program, we will get the following output.

Concatenated string LuaTutorial Length of string1 is 3 LuaLuaLua

Lua — Arrays

Arrays are ordered arrangement of objects, which may be a one-dimensional array containing a collection of rows or a multi-dimensional array containing multiple rows and columns.

In Lua, arrays are implemented using indexing tables with integers. The size of an array is not fixed and it can grow based on our requirements, subject to memory constraints.

One-Dimensional Array

A one-dimensional array can be represented using a simple table structure and can be initialized and read using a simple for loop. An example is shown below.

array = {"Lua", "Tutorial"}

for i = 0, 2 do

print(array[i])

end

When we run the above code, we wil get the following output.

nil Lua Tutorial

As you can see in the above code, when we are trying to access an element in an index that is not there in the array, it returns nil. In Lua, indexing generally starts at index 1. But it is possible to create objects at index 0 and below 0 as well. Array using negative indices is shown below where we initialize the array using a for loop.

array = {}

for i= -2, 2 do

array[i] = i *2

end

for i = -2,2 do

print(array[i])

end

When we run the above code, we will get the following output.

-4 -2 0 2 4

Multi-Dimensional Array

Multi-dimensional arrays can be implemented in two ways.

- Array of arrays

- Single dimensional array by manipulating indices

An example for multidimensional array of 3. 3 is shown below using array of arrays.

-- Initializing the array

array = {}

for i=1,3 do

array[i] = {}

for j=1,3 do

array[i][j] = i*j

end

end

-- Accessing the array

for i=1,3 do

for j=1,3 do

print(array[i][j])

end

end

When we run the above code, we will get the following output.

1 2 3 2 4 6 3 6 9

An example for multidimensional array is shown below using manipulating indices.

-- Initializing the array

array = {}

maxRows = 3

maxColumns = 3

for row=1,maxRows do

for col=1,maxColumns do

array[row*maxColumns +col] = row*col

end

end

-- Accessing the array

for row=1,maxRows do

for col=1,maxColumns do

print(array[row*maxColumns +col])

end

end

When we run the above code, we will get the following output.

1 2 3 2 4 6 3 6 9

As you can see in the above example, data is stored based on indices. It is possible to place the elements in a sparse way and it is the way Lua implementation of a matrix works. Since it does not store nil values in Lua, it is possible to save lots of memory without any special technique in Lua as compared to special techniques used in other programming languages.

Lua — Iterators

Iterator is a construct that enables you to traverse through the elements of the so called collection or container. In Lua, these collections often refer to tables, which are used to create various data structures like array.

Generic For Iterator

A generic for iterator provides the key value pairs of each element in the collection. A simple example is given below.

array = {"Lua", "Tutorial"}

for key,value in ipairs(array)

do

print(key, value)

end

When we run the above code, we will get the following output −

1 Lua 2 Tutorial

The above example uses the default ipairs iterator function provided by Lua.