From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Emblem of the Government of South Korea |

|

| Formation | 15 August 1948; 74 years ago (First Republic) |

|---|---|

| Jurisdiction | |

| Website | www.korea.go.kr |

| Legislative branch | |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Meeting place | National Assembly Building |

| Executive branch | |

| Leader | President of South Korea Prime Minister of South Korea |

| Headquarters | Yongsan District, Seoul |

| Main organ | Cabinet |

| Departments | 18 |

| Judicial branch | |

| Court | Supreme Court |

| Seat | Seocho District, Seoul |

| Court | Constitutional Court |

| Seat | Jongno District, Seoul |

| Government of South Korea | |

| Hangul |

대한민국정부 |

|---|---|

| Hanja |

大韓民國政府 |

| Revised Romanization | Daehanminguk Jeongbu |

| McCune–Reischauer | Taehanmin’guk Chŏngbu |

The Government of South Korea is the national government of the Republic of Korea, created by the Constitution of South Korea as the executive, legislative and judicial authority of the republic. The president acts as the head of state and is the highest figure of executive authority in the country, followed by the prime minister and government ministers in decreasing order.[1]

The Executive and Legislative branches operate primarily at the national level, although various ministries in the executive branch also carry out local functions. Local governments are semi-autonomous and contain executive and legislative bodies of their own. The judicial branch operates at both the national and local levels.

The South Korean government’s structure is determined by the Constitution of the Republic of Korea. This document has been revised several times since its first promulgation in 1948 (for details, see History of South Korea). However, it has retained many broad characteristics; with the exception of the short-lived Second Republic of South Korea, the country has always had a relatively independent chief executive in the form of a president.

As with most stable three-branch systems, a careful system of checks and balances is in place. For instance, the judges of the Constitutional Court are partially appointed by the executive, and partially by the legislature. Likewise, when a resolution of impeachment is passed by the legislature, it is sent to the judiciary for a final decision.

Legislative branch[edit]

The National Assembly building

The main chamber of the National Assembly

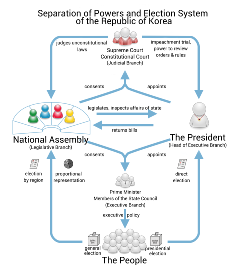

Separation of powers and election system in South Korea

At the national level, the legislative branch consists of the National Assembly of South Korea. This is a unicameral legislature; it consists of a single large assembly. Most of its 300 members are elected from-member constituencies; however, 56 are elected through proportional representation. The members of the National Assembly serve for four years; if a member is unable to complete his or her term, a by-election is held.

The National Assembly is charged with deliberating and passing legislation, auditing the budget and administrative procedures, ratifying treaties, and approving state appointments. In addition, it has the power to impeach or recommend the removal of high officials.

The Assembly forms 17 standing committees to deliberate matters of detailed policy. For the most part, these coincide with the ministries of the executive branch.

Bills pass through these committees before they reach the floor. However, before they reach committee, they must already have gained the support of at least 20 members, unless they have been introduced by the president. To secure final passage, a bill must be approved by a majority of those present; a tie vote defeats the bill. After passage, bills are sent to the president for approval; they must be approved within 15 days.

Each year, the budget bill is submitted to the National Assembly by the executive. By law, it must be submitted at least 90 days before the start of the fiscal year, and the final version must be approved at least 30 days before the start of the fiscal year. The Assembly is also responsible for auditing accounts of past expenditures, which must be submitted at least 120 days before the start of the fiscal year.

Sessions of the Assembly may be either regular (once a year, for no more than 100 days) or extraordinary (by request of the president or a caucus, no more than 30 days). These sessions are open-door by default but can be closed to the public by majority vote or by decree of the Speaker. In order for laws to be passed in any session, a quorum of half the members must be present.

Currently, seven political parties are represented in the National Assembly.

Executive branch[edit]

Main building of Presidential Residence of South Korea, Seoul

The executive branch is headed by the president.[2] The president is elected directly by the people, and is the only elected member of the national executive.[3] The president serves for one five-year term; additional terms are not permitted.[4] The president is head of state, head of government and commander-in-chief of the South Korean armed forces.[5][6] The president is vested with the power to declare war, and can also propose legislation to the National Assembly.[7][8] The president can also declare a state of emergency or martial law, subject to the Assembly’s subsequent approval.[9] The President can veto bills, subject to a two-thirds majority veto override by the National Assembly.[10] However, the president does not have the power to dissolve the National Assembly. This safeguard reflects the experience of authoritarian governments under the First, Third, and Fourth Republics.

The president is assisted in his or her duties by the Prime Minister of South Korea as well as the Presidential Secretariat (대통령비서실, 大統領祕書室).[11] The Prime Minister is appointed by the president upon the approval of the National Assembly, and has the power to recommend the appointment or dismissal of the Cabinet ministers.[12] The officeholder is not required to be a member of the National Assembly. The Prime Minister is assisted in his/her duties by the Prime Minister’s Office which houses both the Office for Government Policy Coordination (국무조정실, 國務調整室) and the Prime Minister’s Secretariat (국무총리비서실, 國務總理祕書室), the former of which is headed by a cabinet-level minister and the latter by a vice minister-level chief of staff.[13] if the president is unable to fulfill his duties, the Prime Minister assumes the president’s powers and takes control of the state until the President can once again fulfill his/her duties or until a new president is elected.[14]

If they are suspected of serious wrongdoing, the president and cabinet-level officials are subject to impeachment by the National Assembly.[15] Once the National Assembly votes in favor of the impeachment the Constitutional Court should either confirm or reject the impeachment resolution, once again reflecting the system of checks and balances between the three branches of the government.[16]

The State Council (국무회의, 國務會議, gungmuhoeui) is the highest body and national cabinet for policy deliberation and resolution in the executive branch of the Republic of Korea. The Constitution of the Republic of Korea mandates that the Cabinet be composed of between 15 and 30 members including the Chairperson, and currently the Cabinet includes the President, the Prime Minister, the Vice Prime Minister (the Minister of Strategy and Finance), and the cabinet-level ministers of the 17 ministries.[17] The Constitution designates the President as the chairperson of the Cabinet and the Prime Minister as the vice chairperson.[18] Nevertheless, the Prime Minister frequently holds the meetings without the presence of the President as the meeting can be lawfully held as long as the majority of the Cabinet members are present at the meeting. Also, as many government agencies have moved out of Seoul into other parts of the country since 2013,[19] the need to hold Cabinet meetings without having to convene in one place at the same time has been growing, and therefore the law has been amended to allow Cabinet meetings in a visual teleconference format.[20] Although not the official members of the Cabinet, the chief presidential secretary (대통령비서실장, 大統領祕書室長), the Minister of the Office for Government Policy Coordination (국무조정실장, 國務調整室長), the Minister of Government Legislation (법제처장, 法制處長), the Minister of Patriots and Veterans Affairs (국가보훈처장, 國家報勳處長), the Minister of Food and Drug Safety (식품의약품안전처장, 食品醫藥品安全處長), the Chairperson of Korea Fair Trade Commission (공정거래위원장, 公正去來委員長), the Chairperson of Financial Services Commission (금융위원장, 金融委員長), the Mayor of Seoul Special City (서울특별시장, 서울特別市長), and other officials designated by law or deemed necessary by the Chairperson of the Cabinet can also attend the Cabinet meetings and speak in front of the Cabinet without the right to vote on the matters discussed in the meetings [21] The Mayor of Seoul, although being the head of a local autonomous region in South Korea and not directly related to the central executive branch, has been allowed to attend the Cabinet meeting considering the special status of Seoul (Special City) and its mayor (the only cabinet-level mayor in Korea).

It has to be noted that the Cabinet of the Republic of Korea performs somewhat different roles than those of many other nations with similar forms. As the Korean political system is basically a presidential system yet with certain aspects of parliamentary cabinet system combined, the Cabinet of the Republic of Korea also is a combination of both systems. More specifically, the Korean Cabinet performs policy resolutions as well as policy consultations to the President. Reflecting that the Republic of Korea is basically a presidential republic the Cabinet resolutions cannot bind the president’s decision, and in this regard, the Korean Cabinet is similar to those advisory counsels in strict presidential republics. At the same time, however, the Constitution of the Republic of Korea specifies in details 17 categories including budgetary and military matters, which necessitates the resolution of the Cabinet in addition to the President’s approval, and in this regard the Korean Cabinet is similar to those cabinets in strict parliamentary cabinet systems.[22]

The official residence and office of the President of the Republic of Korea is Cheongwadae (청와대, 靑瓦臺), located in Jongno-gu, Seoul. The name «Cheongwadae» literally means «the house with blue-tiled roof» and is named as such due to its appearance. In addition to the Office of the President, Cheongwadae (청와대, 靑瓦臺) also houses the Office of National Security (국가안보실, 國家安保室) and the Presidential Security Service (대통령경호실, 大統領警護室) to assist the President.[23]

Ministries[edit]

Government Complex Sejong (Northern portion)

Government Complex Gwacheon

Currently, 18 ministries exist in the South Korean government.[24] The 18 ministers are appointed by the President and report to the Prime Minister. Also, some ministries have affiliated agencies (listed below), which report both to the Prime Minister and to the minister of the affiliated ministry. Each affiliated agency is headed by a vice-minister-level commissioner except Prosecution Service which is led by a minister-level Prosecutor General.

The Minister of Strategy and Finance and the Minister of Education, by law, automatically assume the positions of Deputy Prime Ministers of the Republic of Korea.

The respective ministers of the below ministries assume the President’s position in the below order, if the President cannot perform his/her duty and the Prime Minister cannot assume the President’s position. Also note that the Constitution and the affiliated laws of the Republic of Korea stipulates only so far as the Prime Minister and the 17 ministers as those who can assume the President’s position.[14] Moreover, if the Prime Minister cannot perform his/her duty the Vice Prime Minister will assume the Prime Minister’s position, and if both the Prime Minister and the Vice Prime Minister cannot perform the Prime Minister’s role the President can either pick one of the 17 ministers to assume the Prime Minister’s position or let the 17 ministers assume the position according to the below order.[25]

The commissioner of National Tax Service, a vice-minister-level official by law, is customarily considered to be a minister-level official due to the importance of National Tax Service. For example, the vice-commissioner of the agency will attend meetings where other agencies would send their commissioners, and the commissioner of the agency will attend meetings where minister-level officials convene.

- Ministry of Economy and Finance (기획재정부, 企劃財政部)

- National Tax Service (국세청, 國稅廳)

- Korea Customs Service (관세청, 關稅廳)

- Public Procurement Service (조달청, 調達廳)

- Statistics Korea (통계청, 統計廳)

- Ministry of Education (교육부, 敎育部)

- Ministry of Science and ICT (과학기술정보통신부, 科學技術情報通信部)

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs (외교부, 外交部)

- Ministry of Unification (통일부, 統一部)

- Ministry of Justice (법무부, 法務部)

- Supreme Prosecutors’ Office (검찰청, 檢察廳)

- Ministry of National Defense (국방부, 國防部)

- Military Manpower Administration (병무청, 兵務廳)

- Defense Acquisition Program Administration (방위사업청, 防衛事業廳)

- Ministry of the Interior and Safety (행정안전부, 行政安全部)

- National Police Agency (경찰청, 警察廳)

- National Fire Agency (소방청, 消防廳)

- Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism (문화체육관광부, 文化體育觀光部)

- Cultural Heritage Administration (문화재청, 文化財廳)

- Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (농림축산식품부, 農林畜産食品部)

- Rural Development Administration (농촌진흥청, 農村振興廳)

- Korea Forest Service (산림청, 山林廳)

- Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (산업통상자원부, 産業通商資源部)

- Korean Intellectual Property Office (특허청, 特許廳)

- Ministry of Health and Welfare (보건복지부, 保健福祉部)

- Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (질병관리청, 疾病管理廳)

- Ministry of Environment (환경부, 環境部)

- Korea Meteorological Administration (기상청, 氣象廳)

- Ministry of Employment and Labor (고용노동부, 雇用勞動部)

- Ministry of Gender Equality and Family (여성가족부, 女性家族部)

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (국토교통부, 國土交通部)

- National Agency for Administrative City Construction (행정중심복합도시건설청, 行政中心複合都市建設廳)

- Saemangeum Development and Investment Agency (새만금개발청, 새萬金開發廳)[26]

- Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries (해양수산부, 海洋水産部)

- Korea Coast Guard (해양경찰청, 海洋警察廳)

- Ministry of SMEs and Startups (중소벤처기업부, 中小벤처企業部)

| Department | Formed | Employees | Annual budget | Location | Minister | Minister’s Party | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ministry of Economy and Finance 기획재정부 |

February 29, 2008 | 1,297 (2019) |

21,062 billion (2019) |

Sejong | Choo Kyung-ho | People Power | |

| Ministry of Education 교육부 |

March 23, 2013 | 7,292 (2019) |

74,916 billion (2019) |

Sejong | Lee Ju-ho | Independent | |

| Ministry of Science and ICT 과학기술정보통신부 |

July 26, 2017 | 35,560 (2019) |

14,946 billion (2019) |

Sejong | Lee Jong-ho | Independent | |

| Ministry of Foreign Affairs 외교부 |

March 23, 2013 | 656 (2019) |

2,450 billion (2019) |

Seoul | Park Jin | People Power | |

| Ministry of Unification 통일부 |

March 1, 1969 | 692 (2019) |

1,326 billion (2019) |

Seoul | Kwon Young-se | People Power | |

| Ministry of Justice 법무부 |

July 17, 1948 | 23,135 (2019) |

3,880 billion (2019) |

Gwacheon | Han Dong-hoon | Independent | |

| Ministry of National Defense 국방부 |

August 15, 1948 | 1,095 (2019) |

33,108 billion (2019) |

Seoul | Lee Jong-sup | Independent | |

| Ministry of the Interior and Safety 행정안전부 |

July 26, 2017 | 3,964 (2019) |

55,682 billion (2019) |

Sejong | Lee Sang-min | Independent | |

| Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism 문화체육관광부 |

February 29, 2008 | 2,832 (2019) |

5,923 billion (2019) |

Sejong | Park Bo-gyoon | Independent | |

| Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs 농림축산식품부 |

March 23, 2013 | 3,706 (2019) |

14,660 billion (2019) |

Sejong | Chung Hwang-keun | Independent | |

| Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy 산업통상자원부 |

February 29, 2008 | 1,503 (2019) |

7,693 billion (2019) |

Sejong | Lee Chang-yang | Independent | |

| Ministry of Health and Welfare 보건복지부 |

March 19, 2010 | 3,637 (2019) |

72,515 billion (2019) |

Sejong | Cho Kyoo-hong | Independent | |

| Ministry of Environment 환경부 |

December 24, 1994 | 2,534 (2019) |

7,850 billion (2019) |

Sejong | Han Wha-jin | Independent | |

| Ministry of Employment and Labor 고용노동부 |

July 5, 2010 | 7,552 (2019) |

26,716 billion (2019) |

Sejong | Lee Jeong-sik | Independent | |

| Ministry of Gender Equality and Family 여성가족부 |

March 19, 2010 | 323 (2019) |

1,047 billion (2019) |

Seoul | Kim Hyun-sook | Independent | |

| Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport 국토교통부 |

March 23, 2013 | 4,443 (2019) |

43,219 billion (2019) |

Sejong | Won Hee-ryong | People Power | |

| Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries 해양수산부 |

March 23, 2013 | 3,969 (2019) |

5,180 billion (2019) |

Sejong | Cho Seung-hwan | Independent | |

| Ministry of SMEs and Startups 중소벤처기업부 |

July 26, 2017 | 1,082 (2019) |

10,266 billion (2019) |

Sejong | Lee Young | People Power |

Independent agencies[edit]

The following agencies report directly to the President:

- Board of Audit and Inspection (감사원, 監査院) [27]

-

- The chairperson of the board, responsible for general administrative oversight, must be approved by the National Assembly to be appointed by the President. Also, although the law provides no explicit regulation regarding the chairperson’s rank in the Korean government hierarchy, it is customary to consider the chairperson of the board to enjoy the same rank as a Vice Prime Minister. This is because the law stipulates that the secretary general of the board, the second highest position in the organization, be the rank of minister and therefore the chairperson, directly over the secretary general in the organization, should be at least the rank of Vice Prime Minister in order to be able to control the whole organization without any power clash.

- National Intelligence Service (국가정보원, 國家情報院) [28]

- Korea Communications Commission (방송통신위원회, 放送通信委員會) [29]

- National Human Rights Commission of Korea (국가인권위원회, 國家人權委員會, NHRCK) [30] is an independent agency for protecting and promoting human rights in South Korea. Though the NHRCK regards itself as independent from all three branches of the government, it is officially regarded as an independent administrative agency inside the executive branch,[31] according to judgment by the Constitutional Court of Korea in 2010.[32] It burdens duty to report its annul report directly to the President and the National Assembly, by Article 29 of the National Human Rights Commission of Korea Act.[30]

The following councils advise the president on pertinent issues:

- National Security Council (국가안전보장회의, 國家安全保障會議) [33]

- National Unification Advisory Council (민주평화통일자문회의, 民主平和統一諮問會議) [34]

- National Economic Advisory Council (국민경제자문회의, 國民經濟諮問會議) [35]

- Presidential Advisory Council on Science and Technology (국가과학기술자문회의, 國家科學技術諮問會議) [36]

The following agencies report directly to the Prime Minister:

- Ministry of Patriots and Veterans Affairs (국가보훈처, 國家報勳處) [37]

- Ministry of Personnel Management (인사혁신처, 人事革新處) [38]

- Ministry of Government Legislation (법제처, 法制處) [39]

- Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (식품의약품안전처, 食品醫藥品安全處) [40]

- Fair Trade Commission (공정거래위원회, 公正去來委員會) [41]

- Anti-Corruption and Civil Rights Commission (국민권익위원회, 國民權益委員會) [42]

- Financial Services Commission (금융위원회, 金融委員會) [43]

- Personal Information Protection Commission (South Korea) (개인정보보호위원회, 個人情報保護委員會) [44]

- Nuclear Safety and Security Commission (원자력안전위원회, 原子力安全委員會) [45]

The following agency report only to the National Assembly:

- Corruption Investigation Office for High-ranking Officials (Korean: 고위공직자범죄수사처; Hanja: 高位公職者犯罪搜査處; RR: Gowigongjikjabeomjoe Susacheo, CIO) [46]

-

- It is an independent agency for anti-corruption of high-ranking officials in South Korean government, established by ‘Act On The Establishment And Operation Of The Corruption Investigation Office For High-ranking Officials’.[46] According to judgment by the Constitutional Court of Korea in 2021, the CIO is officially interpreted as an independent agency inside the executive branch of the South Korean government, which means independence from the Cabinet of South Korea and the Office of the President.[47] By article 3(3) and 17(2) of the Act, CIO’s report on the President of South Korea is strictly prohibited, and it only reports to the National Assembly of South Korea.[46]

Relocation of government agencies[edit]

Until 2013, almost all of the central government agencies were located in either Seoul or Gwacheon government complex, with the exception of a few agencies located in Daejeon government complex. Considering that Gwacheon is a city constructed just outside Seoul to house the new government complex, virtually all administrative functions of South Korea were still concentrated in Seoul. It has been decided, however, that government agencies decide if they will relocate themselves to Sejong Special Self-Governing City, which was created from territory comprising South Chungcheong Province, so that government agencies are better accessible from most parts of South Korea and reduce the concentration of government bureaucracy in Seoul. Since the plan was announced, 22 agencies have moved to the new government complex in Sejong.[19][48][49]

The following agencies will settle in the Government Complex Seoul:

- Financial Services Commission (금융위원회)

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs (외교부)

- Ministry of Unification (통일부)

- Ministry of Gender Equality and Family (여성가족부)

The following agencies will settle in Seoul, but in separate locations:

- Board of Audit and Inspection (감사원) will continue to stay in Jongno-gu, Seoul.

- National Intelligence Service (국가정보원) will continue to stay in Seocho-gu, Seoul.

- Nuclear Safety and Security Commission (원자력안전위원회) will continue to stay in Jongno-gu, Seoul.

- National Security Council (국가안전보장회의) will continue to stay in Jongno-gu, Seoul.

- National Unification Advisory Council (민주평화통일자문회의) will continue to stay in Jung-gu, Seoul.

- National Economic Advisory Council (국민경제자문회의) will continue to stay in Jongno-gu, Seoul.

- Presidential Advisory Council on Science and Technology (국가과학기술자문회의) will continue to stay in Jongno-gu, Seoul.

- Ministry of National Defense (국방부) will continue to stay in Yongsan-gu, Seoul.

- Supreme Prosecutors’ Office (검찰청) will continue to stay in Seocho-gu, Seoul.

- National Police Agency (경찰청) will continue to stay in Seodaemun-gu, Seoul.

The following agencies will settle in Government Complex Gwacheon:

- Korea Communications Commission (방송통신위원회)

- Ministry of Justice (법무부)

- Defense Acquisition Program Administration (방위사업청)

The following agencies will settle in Government Complex, Daejeon:

- Korea Customs Service (관세청)

- Public Procurement Service (조달청)

- Statistics Korea (통계청)

- Military Manpower Administration (병무청)

- Cultural Heritage Administration (문화재청)

- Korea Forest Service (산림청)

- Korean Intellectual Property Office (특허청)

- Korea Meteorological Administration (기상청)

The following agencies will settle in Government Complex Sejong:

- Office for Government Policy Coordination, Prime Minister’s Secretariat (국무조정실, 국무총리비서실)

- Ministry of Patriots and Veterans Affairs (국가보훈처)

- Ministry of Personnel Management (인사혁신처)

- Ministry of Government Legislation (법제처)

- Fair Trade Commission (공정거래위원회)

- Anti-Corruption and Civil Rights Commission (국민권익위원회)

- Ministry of Strategy and Finance (기획재정부)

- Ministry of Education (교육부)

- Ministry of Science and ICT (과학기술정보통신부)

- Ministry of the Interior and Safety (행정안전부)

- Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism (문화체육관광부)

- Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (농림축산식품부)

- Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (산업통상자원부)

- Ministry of Health and Welfare (보건복지부)

- Ministry of Environment (환경부)

- Ministry of Employment and Labor (고용노동부)

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (국토교통부)

- Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries (해양수산부)

- Ministry of SMEs and Startups (중소벤처기업부)

- National Tax Service (국세청)

- National Fire Agency (소방청)

- Multifunctional Administrative City Construction Agency (행정중심복합도시건설청)

The following agencies will settle in separate locations:

- Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (식품의약품안전처) will continue to stay in Cheongju, North Chungcheong Province.

- Rural Development Administration (농촌진흥청) will move to Jeonju, North Jeolla Province.

- Saemangeum Development and Investment Agency (새만금개발청) will move to Saemangeum development project area.

- Korea Coast Guard (해양경찰청) will continue to stay in Songdo, Yeonsu-gu, Incheon Metropolitan City.

Judicial branch[edit]

The Supreme Court building in Seocho, Seoul

The Constitutional Court building in Jongno, Seoul

The judicial branch of South Korea is organized into two groups. One is the Constitutional Court which is the highest court on adjudication of matters on constitutionality, including judicial review and constitutional review. Another is ordinary courts on matters except jurisdiction of Constitutional Court. These ordinary courts are regarding the Supreme Court as the highest court. Both the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and the President of the Constitutional Court have equivalent status as two heads of the judiciary branch in South Korea.

Elections[edit]

Elections in South Korea are held on national level to select the President and the National Assembly. South Korea has a multi-party system, with two dominant parties and numerous third parties. Elections are overseen by the Electoral Branch of the National Election Commission. The most recent presidential election was held on 9 March 2022.

The president is directly elected for a single five-year term by plurality vote. The National Assembly has 300 members elected for a four-year term, 253 in single-seat constituencies and 47 members by proportional representation. Each individual party intending to represent its policies in the National Assembly must be qualified through the assembly’s general election by either: i) the national party-vote reaching over 3.00% on a proportional basis or ii) more than 5 members of their party being elected in each of their first-past-the-post election constituencies.[50]

Local governments[edit]

Local autonomy was established as a constitutional principle of South Korea beginning with the First Republic. However, for much of the 20th century this principle was not honored. From 1965 to 1995, local governments were run directly by provincial governments, which in turn were run directly by the national government. However, since the elections of 1995, a degree of local autonomy has been restored. Local magistrates and assemblies are elected in each of the primary and secondary administrative divisions of South Korea, that is, in every province, metropolitan or special city, and district. Officials at lower levels, such as eup and dong, are appointed by the city or county government.

As noted above, local autonomy does not extend to the judicial branch. It also does not yet extend to many other areas, including fire protection and education, which are managed by independent national agencies. Local governments also have very limited policy-making authority; generally, the most that they can do is decide how national policies will be implemented. However, there is some political pressure for the scope of local autonomy to be extended.

Although the chief executive of each district is locally elected, deputy executives are still appointed by the central government. It is these deputy officials who have detailed authority over most administrative matters.

Civil service[edit]

The South Korean civil service is managed by the Ministry of Personnel Management. This is large, and remains a largely closed system, although efforts at openness and reform are ongoing. In order to gain a position in civil service, it is usually necessary to pass one or more difficult examinations. Positions have traditionally been handed out based on seniority, in a complex graded system; however, this system was substantially reformed in 1998.

There are more than 800,000 civil servants in South Korea today. More than half of these are employed by the central government; only about 300,000 are employed by local governments. In addition, only a few thousand each are employed by the national legislative and judicial branches; the overwhelming majority are employed in the various ministries of the executive branch. The size of the civil service increased steadily from the 1950s to the late 1990s, but has dropped slightly since 1995.

The civil service, not including political appointees and elected officials, is composed of career civil servants and contract civil servants. Contract servants are typically paid higher wages and hired for specific jobs. Career civil servants make up the bulk of the civil service, and are arranged in a nine-tiered system in which grade 1 is occupied by assistant ministers and grade 9 by the newest and lowest-level employees. Promotions are decided by a combination of seniority, training, and performance review. Civil servants’ base salary makes up less than half of their annual pay; the remainder is supplied in a complex system of bonuses. Contract civil servants are paid on the basis of the competitive rates of pay in the private sector.[citation needed]

Gallery[edit]

-

Emblem of the Government of South Korea (1949–2016)

-

Flag of the Government of South Korea (1949–2016)

-

Flag of the Government of South Korea (from 2016)

See also[edit]

- Government of North Korea

- Politics of South Korea

- National Assembly

- Judiciary of South Korea

References[edit]

- ^ «What Type Of Government Does South Korea Have?». WorldAtlas. 28 March 2019. Retrieved 2020-01-06.

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제4장 제1절 제66조

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제4장 제1절 제67조

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제4장 제1절 제70조

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제4장 제1절 제66조 제1항, 제4항

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제4장 제1절 제74조

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제4장 제1절 제73조

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제3장 제52조

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제4장 제1절 제76조, 제77조

- ^ Article 53 of the Constitution of the Republic of Korea.

- ^ 대한민국 정부조직법 제2장 제14조

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제4장 제2절 제1관 제86조

- ^ 대한민국 정부조직법 제3장 제20조, 제21조

- ^ a b 대한민국 헌법 제4장 제1절 제71조

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제3장 제65조

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제6장 제111조 제1항의2

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제4장 제2절 제2관 제88조 제2항

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제4장 제2절 제2관 제88조 제3항

- ^ a b Lyu, Hyeon-Suk; Hong, Seung-Hee (2013). «세종시 정부청사 이전에 따른 공무원의 일과 삶의 만족도 분석» [An Empirical Study on the issues and concerns associated with the diversification of government ministers in Sejong city.]. 현대사회와 행정 (in Korean). 23 (3): 203–224. ISSN 1229-389X.

- ^ 대한민국 국무회의 규정 제6조 제2항

- ^ 대한민국 국무회의 규정 제8조

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제4장 제2절 제2관 제89조

- ^ 대한민국 정부조직법 제2장 제15조, 제16조

- ^ 대한민국 정부조직법 제4장 행정각부

- ^ 대한민국 정부조직법 제3장 제22조

- ^ Established to consolidate most Saemangeum development projects and their support functions (currently provided by many different government bodies) into a single government agency for maximum efficiency. Commenced operation on September 12th, 2013.

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제4장 제2절 제4관 감사원

- ^ 대한민국 정부조직법 제2장 제17조

- ^ 대한민국 방송통신위원회의 설치 및 운영에 관한 법률 제2장 제3조

- ^ a b «National Human Rights Commission Of Korea Act». Korea Legislation Research Institute. Retrieved 2022-05-01.

- ^ «Kim, J. (2013). Constitutional Law. In: Introduction to Korean Law. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. pp. 52-54». doi:10.1007/978-3-642-31689-0_2. Retrieved 2022-05-01.

- ^ «2009Hun-Ra6, October 28, 2010» (in Korean). Retrieved 2022-05-01.

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제4장 제2절 제2관 제91조

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제4장 제2절 제2관 제92조

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제4장 제2절 제2관 제93조

- ^ 대한민국 국가과학기술자문회의법 제1조

- ^ 대한민국 정부조직법 제3장 제22조의 2

- ^ 대한민국 정부조직법 제3장 제22조의 3

- ^ 대한민국 정부조직법 제3장 제23조

- ^ 대한민국 정부조직법 제3장 제25조

- ^ 대한민국 독점규제 및 공정거래에 관한 법률 제9장 제35조

- ^ 대한민국 부패방지 및 국민권익위원회의 설치와 운영에 관한 법률 제2장 제11조

- ^ 대한민국 금융위원회의 설치 등에 관한 법률 제2장 제1절 제3조

- ^ 개인정보 보호법 제2장 제7조

- ^ 대한민국 원자력안전위원회의 설치 및 운영에 관한 법률 제2장 제3조

- ^ a b c «Act On The Establishment And Operation Of The Corruption Investigation Office For High-ranking Officials». Korea Legislation Research Institute. Retrieved 2022-05-01.

- ^ «2020Hun-Ma264, January 28, 2021» (in Korean). Retrieved 2022-05-01.

- ^ «안전행정부 정부청사관리소». Archived from the original on 2013-05-31. Retrieved 2013-03-25.

- ^ «국토교통부 행정중심복합도시건설청». Archived from the original on 2007-09-12. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ^ Representation System(Elected Person) Archived 2008-04-22 at the Wayback Machine, the NEC, Retrieved on April 10, 2008

Further reading[edit]

- Korea Overseas Information Service (2003). Handbook of Korea, 11th ed. Seoul: Hollym. ISBN 978-1-56591-212-0.

- Kim, Jongcheol (2012). Constitutional Law. In: Introduction to Korean Law. Berlin, Heidelberg.: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-31689-0_2. ISBN 978-3-642-31689-0.

External links[edit]

- Official website

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Government of the Republic of Korea

Emblem of the Government of South Korea |

|

| Formation | 15 August 1948; 74 years ago (First Republic) |

|---|---|

| Jurisdiction | |

| Website | www.korea.go.kr |

| Legislative branch | |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Meeting place | National Assembly Building |

| Executive branch | |

| Leader | President of South Korea Prime Minister of South Korea |

| Headquarters | Yongsan District, Seoul |

| Main organ | Cabinet |

| Departments | 18 |

| Judicial branch | |

| Court | Supreme Court |

| Seat | Seocho District, Seoul |

| Court | Constitutional Court |

| Seat | Jongno District, Seoul |

| Government of South Korea | |

| Hangul |

대한민국정부 |

|---|---|

| Hanja |

大韓民國政府 |

| Revised Romanization | Daehanminguk Jeongbu |

| McCune–Reischauer | Taehanmin’guk Chŏngbu |

The Government of South Korea is the national government of the Republic of Korea, created by the Constitution of South Korea as the executive, legislative and judicial authority of the republic. The president acts as the head of state and is the highest figure of executive authority in the country, followed by the prime minister and government ministers in decreasing order.[1]

The Executive and Legislative branches operate primarily at the national level, although various ministries in the executive branch also carry out local functions. Local governments are semi-autonomous and contain executive and legislative bodies of their own. The judicial branch operates at both the national and local levels.

The South Korean government’s structure is determined by the Constitution of the Republic of Korea. This document has been revised several times since its first promulgation in 1948 (for details, see History of South Korea). However, it has retained many broad characteristics; with the exception of the short-lived Second Republic of South Korea, the country has always had a relatively independent chief executive in the form of a president.

As with most stable three-branch systems, a careful system of checks and balances is in place. For instance, the judges of the Constitutional Court are partially appointed by the executive, and partially by the legislature. Likewise, when a resolution of impeachment is passed by the legislature, it is sent to the judiciary for a final decision.

Legislative branch[edit]

The National Assembly building

The main chamber of the National Assembly

Separation of powers and election system in South Korea

At the national level, the legislative branch consists of the National Assembly of South Korea. This is a unicameral legislature; it consists of a single large assembly. Most of its 300 members are elected from-member constituencies; however, 56 are elected through proportional representation. The members of the National Assembly serve for four years; if a member is unable to complete his or her term, a by-election is held.

The National Assembly is charged with deliberating and passing legislation, auditing the budget and administrative procedures, ratifying treaties, and approving state appointments. In addition, it has the power to impeach or recommend the removal of high officials.

The Assembly forms 17 standing committees to deliberate matters of detailed policy. For the most part, these coincide with the ministries of the executive branch.

Bills pass through these committees before they reach the floor. However, before they reach committee, they must already have gained the support of at least 20 members, unless they have been introduced by the president. To secure final passage, a bill must be approved by a majority of those present; a tie vote defeats the bill. After passage, bills are sent to the president for approval; they must be approved within 15 days.

Each year, the budget bill is submitted to the National Assembly by the executive. By law, it must be submitted at least 90 days before the start of the fiscal year, and the final version must be approved at least 30 days before the start of the fiscal year. The Assembly is also responsible for auditing accounts of past expenditures, which must be submitted at least 120 days before the start of the fiscal year.

Sessions of the Assembly may be either regular (once a year, for no more than 100 days) or extraordinary (by request of the president or a caucus, no more than 30 days). These sessions are open-door by default but can be closed to the public by majority vote or by decree of the Speaker. In order for laws to be passed in any session, a quorum of half the members must be present.

Currently, seven political parties are represented in the National Assembly.

Executive branch[edit]

Main building of Presidential Residence of South Korea, Seoul

The executive branch is headed by the president.[2] The president is elected directly by the people, and is the only elected member of the national executive.[3] The president serves for one five-year term; additional terms are not permitted.[4] The president is head of state, head of government and commander-in-chief of the South Korean armed forces.[5][6] The president is vested with the power to declare war, and can also propose legislation to the National Assembly.[7][8] The president can also declare a state of emergency or martial law, subject to the Assembly’s subsequent approval.[9] The President can veto bills, subject to a two-thirds majority veto override by the National Assembly.[10] However, the president does not have the power to dissolve the National Assembly. This safeguard reflects the experience of authoritarian governments under the First, Third, and Fourth Republics.

The president is assisted in his or her duties by the Prime Minister of South Korea as well as the Presidential Secretariat (대통령비서실, 大統領祕書室).[11] The Prime Minister is appointed by the president upon the approval of the National Assembly, and has the power to recommend the appointment or dismissal of the Cabinet ministers.[12] The officeholder is not required to be a member of the National Assembly. The Prime Minister is assisted in his/her duties by the Prime Minister’s Office which houses both the Office for Government Policy Coordination (국무조정실, 國務調整室) and the Prime Minister’s Secretariat (국무총리비서실, 國務總理祕書室), the former of which is headed by a cabinet-level minister and the latter by a vice minister-level chief of staff.[13] if the president is unable to fulfill his duties, the Prime Minister assumes the president’s powers and takes control of the state until the President can once again fulfill his/her duties or until a new president is elected.[14]

If they are suspected of serious wrongdoing, the president and cabinet-level officials are subject to impeachment by the National Assembly.[15] Once the National Assembly votes in favor of the impeachment the Constitutional Court should either confirm or reject the impeachment resolution, once again reflecting the system of checks and balances between the three branches of the government.[16]

The State Council (국무회의, 國務會議, gungmuhoeui) is the highest body and national cabinet for policy deliberation and resolution in the executive branch of the Republic of Korea. The Constitution of the Republic of Korea mandates that the Cabinet be composed of between 15 and 30 members including the Chairperson, and currently the Cabinet includes the President, the Prime Minister, the Vice Prime Minister (the Minister of Strategy and Finance), and the cabinet-level ministers of the 17 ministries.[17] The Constitution designates the President as the chairperson of the Cabinet and the Prime Minister as the vice chairperson.[18] Nevertheless, the Prime Minister frequently holds the meetings without the presence of the President as the meeting can be lawfully held as long as the majority of the Cabinet members are present at the meeting. Also, as many government agencies have moved out of Seoul into other parts of the country since 2013,[19] the need to hold Cabinet meetings without having to convene in one place at the same time has been growing, and therefore the law has been amended to allow Cabinet meetings in a visual teleconference format.[20] Although not the official members of the Cabinet, the chief presidential secretary (대통령비서실장, 大統領祕書室長), the Minister of the Office for Government Policy Coordination (국무조정실장, 國務調整室長), the Minister of Government Legislation (법제처장, 法制處長), the Minister of Patriots and Veterans Affairs (국가보훈처장, 國家報勳處長), the Minister of Food and Drug Safety (식품의약품안전처장, 食品醫藥品安全處長), the Chairperson of Korea Fair Trade Commission (공정거래위원장, 公正去來委員長), the Chairperson of Financial Services Commission (금융위원장, 金融委員長), the Mayor of Seoul Special City (서울특별시장, 서울特別市長), and other officials designated by law or deemed necessary by the Chairperson of the Cabinet can also attend the Cabinet meetings and speak in front of the Cabinet without the right to vote on the matters discussed in the meetings [21] The Mayor of Seoul, although being the head of a local autonomous region in South Korea and not directly related to the central executive branch, has been allowed to attend the Cabinet meeting considering the special status of Seoul (Special City) and its mayor (the only cabinet-level mayor in Korea).

It has to be noted that the Cabinet of the Republic of Korea performs somewhat different roles than those of many other nations with similar forms. As the Korean political system is basically a presidential system yet with certain aspects of parliamentary cabinet system combined, the Cabinet of the Republic of Korea also is a combination of both systems. More specifically, the Korean Cabinet performs policy resolutions as well as policy consultations to the President. Reflecting that the Republic of Korea is basically a presidential republic the Cabinet resolutions cannot bind the president’s decision, and in this regard, the Korean Cabinet is similar to those advisory counsels in strict presidential republics. At the same time, however, the Constitution of the Republic of Korea specifies in details 17 categories including budgetary and military matters, which necessitates the resolution of the Cabinet in addition to the President’s approval, and in this regard the Korean Cabinet is similar to those cabinets in strict parliamentary cabinet systems.[22]

The official residence and office of the President of the Republic of Korea is Cheongwadae (청와대, 靑瓦臺), located in Jongno-gu, Seoul. The name «Cheongwadae» literally means «the house with blue-tiled roof» and is named as such due to its appearance. In addition to the Office of the President, Cheongwadae (청와대, 靑瓦臺) also houses the Office of National Security (국가안보실, 國家安保室) and the Presidential Security Service (대통령경호실, 大統領警護室) to assist the President.[23]

Ministries[edit]

Government Complex Sejong (Northern portion)

Government Complex Gwacheon

Currently, 18 ministries exist in the South Korean government.[24] The 18 ministers are appointed by the President and report to the Prime Minister. Also, some ministries have affiliated agencies (listed below), which report both to the Prime Minister and to the minister of the affiliated ministry. Each affiliated agency is headed by a vice-minister-level commissioner except Prosecution Service which is led by a minister-level Prosecutor General.

The Minister of Strategy and Finance and the Minister of Education, by law, automatically assume the positions of Deputy Prime Ministers of the Republic of Korea.

The respective ministers of the below ministries assume the President’s position in the below order, if the President cannot perform his/her duty and the Prime Minister cannot assume the President’s position. Also note that the Constitution and the affiliated laws of the Republic of Korea stipulates only so far as the Prime Minister and the 17 ministers as those who can assume the President’s position.[14] Moreover, if the Prime Minister cannot perform his/her duty the Vice Prime Minister will assume the Prime Minister’s position, and if both the Prime Minister and the Vice Prime Minister cannot perform the Prime Minister’s role the President can either pick one of the 17 ministers to assume the Prime Minister’s position or let the 17 ministers assume the position according to the below order.[25]

The commissioner of National Tax Service, a vice-minister-level official by law, is customarily considered to be a minister-level official due to the importance of National Tax Service. For example, the vice-commissioner of the agency will attend meetings where other agencies would send their commissioners, and the commissioner of the agency will attend meetings where minister-level officials convene.

- Ministry of Economy and Finance (기획재정부, 企劃財政部)

- National Tax Service (국세청, 國稅廳)

- Korea Customs Service (관세청, 關稅廳)

- Public Procurement Service (조달청, 調達廳)

- Statistics Korea (통계청, 統計廳)

- Ministry of Education (교육부, 敎育部)

- Ministry of Science and ICT (과학기술정보통신부, 科學技術情報通信部)

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs (외교부, 外交部)

- Ministry of Unification (통일부, 統一部)

- Ministry of Justice (법무부, 法務部)

- Supreme Prosecutors’ Office (검찰청, 檢察廳)

- Ministry of National Defense (국방부, 國防部)

- Military Manpower Administration (병무청, 兵務廳)

- Defense Acquisition Program Administration (방위사업청, 防衛事業廳)

- Ministry of the Interior and Safety (행정안전부, 行政安全部)

- National Police Agency (경찰청, 警察廳)

- National Fire Agency (소방청, 消防廳)

- Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism (문화체육관광부, 文化體育觀光部)

- Cultural Heritage Administration (문화재청, 文化財廳)

- Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (농림축산식품부, 農林畜産食品部)

- Rural Development Administration (농촌진흥청, 農村振興廳)

- Korea Forest Service (산림청, 山林廳)

- Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (산업통상자원부, 産業通商資源部)

- Korean Intellectual Property Office (특허청, 特許廳)

- Ministry of Health and Welfare (보건복지부, 保健福祉部)

- Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (질병관리청, 疾病管理廳)

- Ministry of Environment (환경부, 環境部)

- Korea Meteorological Administration (기상청, 氣象廳)

- Ministry of Employment and Labor (고용노동부, 雇用勞動部)

- Ministry of Gender Equality and Family (여성가족부, 女性家族部)

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (국토교통부, 國土交通部)

- National Agency for Administrative City Construction (행정중심복합도시건설청, 行政中心複合都市建設廳)

- Saemangeum Development and Investment Agency (새만금개발청, 새萬金開發廳)[26]

- Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries (해양수산부, 海洋水産部)

- Korea Coast Guard (해양경찰청, 海洋警察廳)

- Ministry of SMEs and Startups (중소벤처기업부, 中小벤처企業部)

| Department | Formed | Employees | Annual budget | Location | Minister | Minister’s Party | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ministry of Economy and Finance 기획재정부 |

February 29, 2008 | 1,297 (2019) |

21,062 billion (2019) |

Sejong | Choo Kyung-ho | People Power | |

| Ministry of Education 교육부 |

March 23, 2013 | 7,292 (2019) |

74,916 billion (2019) |

Sejong | Lee Ju-ho | Independent | |

| Ministry of Science and ICT 과학기술정보통신부 |

July 26, 2017 | 35,560 (2019) |

14,946 billion (2019) |

Sejong | Lee Jong-ho | Independent | |

| Ministry of Foreign Affairs 외교부 |

March 23, 2013 | 656 (2019) |

2,450 billion (2019) |

Seoul | Park Jin | People Power | |

| Ministry of Unification 통일부 |

March 1, 1969 | 692 (2019) |

1,326 billion (2019) |

Seoul | Kwon Young-se | People Power | |

| Ministry of Justice 법무부 |

July 17, 1948 | 23,135 (2019) |

3,880 billion (2019) |

Gwacheon | Han Dong-hoon | Independent | |

| Ministry of National Defense 국방부 |

August 15, 1948 | 1,095 (2019) |

33,108 billion (2019) |

Seoul | Lee Jong-sup | Independent | |

| Ministry of the Interior and Safety 행정안전부 |

July 26, 2017 | 3,964 (2019) |

55,682 billion (2019) |

Sejong | Lee Sang-min | Independent | |

| Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism 문화체육관광부 |

February 29, 2008 | 2,832 (2019) |

5,923 billion (2019) |

Sejong | Park Bo-gyoon | Independent | |

| Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs 농림축산식품부 |

March 23, 2013 | 3,706 (2019) |

14,660 billion (2019) |

Sejong | Chung Hwang-keun | Independent | |

| Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy 산업통상자원부 |

February 29, 2008 | 1,503 (2019) |

7,693 billion (2019) |

Sejong | Lee Chang-yang | Independent | |

| Ministry of Health and Welfare 보건복지부 |

March 19, 2010 | 3,637 (2019) |

72,515 billion (2019) |

Sejong | Cho Kyoo-hong | Independent | |

| Ministry of Environment 환경부 |

December 24, 1994 | 2,534 (2019) |

7,850 billion (2019) |

Sejong | Han Wha-jin | Independent | |

| Ministry of Employment and Labor 고용노동부 |

July 5, 2010 | 7,552 (2019) |

26,716 billion (2019) |

Sejong | Lee Jeong-sik | Independent | |

| Ministry of Gender Equality and Family 여성가족부 |

March 19, 2010 | 323 (2019) |

1,047 billion (2019) |

Seoul | Kim Hyun-sook | Independent | |

| Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport 국토교통부 |

March 23, 2013 | 4,443 (2019) |

43,219 billion (2019) |

Sejong | Won Hee-ryong | People Power | |

| Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries 해양수산부 |

March 23, 2013 | 3,969 (2019) |

5,180 billion (2019) |

Sejong | Cho Seung-hwan | Independent | |

| Ministry of SMEs and Startups 중소벤처기업부 |

July 26, 2017 | 1,082 (2019) |

10,266 billion (2019) |

Sejong | Lee Young | People Power |

Independent agencies[edit]

The following agencies report directly to the President:

- Board of Audit and Inspection (감사원, 監査院) [27]

-

- The chairperson of the board, responsible for general administrative oversight, must be approved by the National Assembly to be appointed by the President. Also, although the law provides no explicit regulation regarding the chairperson’s rank in the Korean government hierarchy, it is customary to consider the chairperson of the board to enjoy the same rank as a Vice Prime Minister. This is because the law stipulates that the secretary general of the board, the second highest position in the organization, be the rank of minister and therefore the chairperson, directly over the secretary general in the organization, should be at least the rank of Vice Prime Minister in order to be able to control the whole organization without any power clash.

- National Intelligence Service (국가정보원, 國家情報院) [28]

- Korea Communications Commission (방송통신위원회, 放送通信委員會) [29]

- National Human Rights Commission of Korea (국가인권위원회, 國家人權委員會, NHRCK) [30] is an independent agency for protecting and promoting human rights in South Korea. Though the NHRCK regards itself as independent from all three branches of the government, it is officially regarded as an independent administrative agency inside the executive branch,[31] according to judgment by the Constitutional Court of Korea in 2010.[32] It burdens duty to report its annul report directly to the President and the National Assembly, by Article 29 of the National Human Rights Commission of Korea Act.[30]

The following councils advise the president on pertinent issues:

- National Security Council (국가안전보장회의, 國家安全保障會議) [33]

- National Unification Advisory Council (민주평화통일자문회의, 民主平和統一諮問會議) [34]

- National Economic Advisory Council (국민경제자문회의, 國民經濟諮問會議) [35]

- Presidential Advisory Council on Science and Technology (국가과학기술자문회의, 國家科學技術諮問會議) [36]

The following agencies report directly to the Prime Minister:

- Ministry of Patriots and Veterans Affairs (국가보훈처, 國家報勳處) [37]

- Ministry of Personnel Management (인사혁신처, 人事革新處) [38]

- Ministry of Government Legislation (법제처, 法制處) [39]

- Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (식품의약품안전처, 食品醫藥品安全處) [40]

- Fair Trade Commission (공정거래위원회, 公正去來委員會) [41]

- Anti-Corruption and Civil Rights Commission (국민권익위원회, 國民權益委員會) [42]

- Financial Services Commission (금융위원회, 金融委員會) [43]

- Personal Information Protection Commission (South Korea) (개인정보보호위원회, 個人情報保護委員會) [44]

- Nuclear Safety and Security Commission (원자력안전위원회, 原子力安全委員會) [45]

The following agency report only to the National Assembly:

- Corruption Investigation Office for High-ranking Officials (Korean: 고위공직자범죄수사처; Hanja: 高位公職者犯罪搜査處; RR: Gowigongjikjabeomjoe Susacheo, CIO) [46]

-

- It is an independent agency for anti-corruption of high-ranking officials in South Korean government, established by ‘Act On The Establishment And Operation Of The Corruption Investigation Office For High-ranking Officials’.[46] According to judgment by the Constitutional Court of Korea in 2021, the CIO is officially interpreted as an independent agency inside the executive branch of the South Korean government, which means independence from the Cabinet of South Korea and the Office of the President.[47] By article 3(3) and 17(2) of the Act, CIO’s report on the President of South Korea is strictly prohibited, and it only reports to the National Assembly of South Korea.[46]

Relocation of government agencies[edit]

Until 2013, almost all of the central government agencies were located in either Seoul or Gwacheon government complex, with the exception of a few agencies located in Daejeon government complex. Considering that Gwacheon is a city constructed just outside Seoul to house the new government complex, virtually all administrative functions of South Korea were still concentrated in Seoul. It has been decided, however, that government agencies decide if they will relocate themselves to Sejong Special Self-Governing City, which was created from territory comprising South Chungcheong Province, so that government agencies are better accessible from most parts of South Korea and reduce the concentration of government bureaucracy in Seoul. Since the plan was announced, 22 agencies have moved to the new government complex in Sejong.[19][48][49]

The following agencies will settle in the Government Complex Seoul:

- Financial Services Commission (금융위원회)

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs (외교부)

- Ministry of Unification (통일부)

- Ministry of Gender Equality and Family (여성가족부)

The following agencies will settle in Seoul, but in separate locations:

- Board of Audit and Inspection (감사원) will continue to stay in Jongno-gu, Seoul.

- National Intelligence Service (국가정보원) will continue to stay in Seocho-gu, Seoul.

- Nuclear Safety and Security Commission (원자력안전위원회) will continue to stay in Jongno-gu, Seoul.

- National Security Council (국가안전보장회의) will continue to stay in Jongno-gu, Seoul.

- National Unification Advisory Council (민주평화통일자문회의) will continue to stay in Jung-gu, Seoul.

- National Economic Advisory Council (국민경제자문회의) will continue to stay in Jongno-gu, Seoul.

- Presidential Advisory Council on Science and Technology (국가과학기술자문회의) will continue to stay in Jongno-gu, Seoul.

- Ministry of National Defense (국방부) will continue to stay in Yongsan-gu, Seoul.

- Supreme Prosecutors’ Office (검찰청) will continue to stay in Seocho-gu, Seoul.

- National Police Agency (경찰청) will continue to stay in Seodaemun-gu, Seoul.

The following agencies will settle in Government Complex Gwacheon:

- Korea Communications Commission (방송통신위원회)

- Ministry of Justice (법무부)

- Defense Acquisition Program Administration (방위사업청)

The following agencies will settle in Government Complex, Daejeon:

- Korea Customs Service (관세청)

- Public Procurement Service (조달청)

- Statistics Korea (통계청)

- Military Manpower Administration (병무청)

- Cultural Heritage Administration (문화재청)

- Korea Forest Service (산림청)

- Korean Intellectual Property Office (특허청)

- Korea Meteorological Administration (기상청)

The following agencies will settle in Government Complex Sejong:

- Office for Government Policy Coordination, Prime Minister’s Secretariat (국무조정실, 국무총리비서실)

- Ministry of Patriots and Veterans Affairs (국가보훈처)

- Ministry of Personnel Management (인사혁신처)

- Ministry of Government Legislation (법제처)

- Fair Trade Commission (공정거래위원회)

- Anti-Corruption and Civil Rights Commission (국민권익위원회)

- Ministry of Strategy and Finance (기획재정부)

- Ministry of Education (교육부)

- Ministry of Science and ICT (과학기술정보통신부)

- Ministry of the Interior and Safety (행정안전부)

- Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism (문화체육관광부)

- Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (농림축산식품부)

- Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (산업통상자원부)

- Ministry of Health and Welfare (보건복지부)

- Ministry of Environment (환경부)

- Ministry of Employment and Labor (고용노동부)

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (국토교통부)

- Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries (해양수산부)

- Ministry of SMEs and Startups (중소벤처기업부)

- National Tax Service (국세청)

- National Fire Agency (소방청)

- Multifunctional Administrative City Construction Agency (행정중심복합도시건설청)

The following agencies will settle in separate locations:

- Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (식품의약품안전처) will continue to stay in Cheongju, North Chungcheong Province.

- Rural Development Administration (농촌진흥청) will move to Jeonju, North Jeolla Province.

- Saemangeum Development and Investment Agency (새만금개발청) will move to Saemangeum development project area.

- Korea Coast Guard (해양경찰청) will continue to stay in Songdo, Yeonsu-gu, Incheon Metropolitan City.

Judicial branch[edit]

The Supreme Court building in Seocho, Seoul

The Constitutional Court building in Jongno, Seoul

The judicial branch of South Korea is organized into two groups. One is the Constitutional Court which is the highest court on adjudication of matters on constitutionality, including judicial review and constitutional review. Another is ordinary courts on matters except jurisdiction of Constitutional Court. These ordinary courts are regarding the Supreme Court as the highest court. Both the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and the President of the Constitutional Court have equivalent status as two heads of the judiciary branch in South Korea.

Elections[edit]

Elections in South Korea are held on national level to select the President and the National Assembly. South Korea has a multi-party system, with two dominant parties and numerous third parties. Elections are overseen by the Electoral Branch of the National Election Commission. The most recent presidential election was held on 9 March 2022.

The president is directly elected for a single five-year term by plurality vote. The National Assembly has 300 members elected for a four-year term, 253 in single-seat constituencies and 47 members by proportional representation. Each individual party intending to represent its policies in the National Assembly must be qualified through the assembly’s general election by either: i) the national party-vote reaching over 3.00% on a proportional basis or ii) more than 5 members of their party being elected in each of their first-past-the-post election constituencies.[50]

Local governments[edit]

Local autonomy was established as a constitutional principle of South Korea beginning with the First Republic. However, for much of the 20th century this principle was not honored. From 1965 to 1995, local governments were run directly by provincial governments, which in turn were run directly by the national government. However, since the elections of 1995, a degree of local autonomy has been restored. Local magistrates and assemblies are elected in each of the primary and secondary administrative divisions of South Korea, that is, in every province, metropolitan or special city, and district. Officials at lower levels, such as eup and dong, are appointed by the city or county government.

As noted above, local autonomy does not extend to the judicial branch. It also does not yet extend to many other areas, including fire protection and education, which are managed by independent national agencies. Local governments also have very limited policy-making authority; generally, the most that they can do is decide how national policies will be implemented. However, there is some political pressure for the scope of local autonomy to be extended.

Although the chief executive of each district is locally elected, deputy executives are still appointed by the central government. It is these deputy officials who have detailed authority over most administrative matters.

Civil service[edit]

The South Korean civil service is managed by the Ministry of Personnel Management. This is large, and remains a largely closed system, although efforts at openness and reform are ongoing. In order to gain a position in civil service, it is usually necessary to pass one or more difficult examinations. Positions have traditionally been handed out based on seniority, in a complex graded system; however, this system was substantially reformed in 1998.

There are more than 800,000 civil servants in South Korea today. More than half of these are employed by the central government; only about 300,000 are employed by local governments. In addition, only a few thousand each are employed by the national legislative and judicial branches; the overwhelming majority are employed in the various ministries of the executive branch. The size of the civil service increased steadily from the 1950s to the late 1990s, but has dropped slightly since 1995.

The civil service, not including political appointees and elected officials, is composed of career civil servants and contract civil servants. Contract servants are typically paid higher wages and hired for specific jobs. Career civil servants make up the bulk of the civil service, and are arranged in a nine-tiered system in which grade 1 is occupied by assistant ministers and grade 9 by the newest and lowest-level employees. Promotions are decided by a combination of seniority, training, and performance review. Civil servants’ base salary makes up less than half of their annual pay; the remainder is supplied in a complex system of bonuses. Contract civil servants are paid on the basis of the competitive rates of pay in the private sector.[citation needed]

Gallery[edit]

-

Emblem of the Government of South Korea (1949–2016)

-

Flag of the Government of South Korea (1949–2016)

-

Flag of the Government of South Korea (from 2016)

See also[edit]

- Government of North Korea

- Politics of South Korea

- National Assembly

- Judiciary of South Korea

References[edit]

- ^ «What Type Of Government Does South Korea Have?». WorldAtlas. 28 March 2019. Retrieved 2020-01-06.

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제4장 제1절 제66조

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제4장 제1절 제67조

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제4장 제1절 제70조

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제4장 제1절 제66조 제1항, 제4항

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제4장 제1절 제74조

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제4장 제1절 제73조

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제3장 제52조

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제4장 제1절 제76조, 제77조

- ^ Article 53 of the Constitution of the Republic of Korea.

- ^ 대한민국 정부조직법 제2장 제14조

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제4장 제2절 제1관 제86조

- ^ 대한민국 정부조직법 제3장 제20조, 제21조

- ^ a b 대한민국 헌법 제4장 제1절 제71조

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제3장 제65조

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제6장 제111조 제1항의2

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제4장 제2절 제2관 제88조 제2항

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제4장 제2절 제2관 제88조 제3항

- ^ a b Lyu, Hyeon-Suk; Hong, Seung-Hee (2013). «세종시 정부청사 이전에 따른 공무원의 일과 삶의 만족도 분석» [An Empirical Study on the issues and concerns associated with the diversification of government ministers in Sejong city.]. 현대사회와 행정 (in Korean). 23 (3): 203–224. ISSN 1229-389X.

- ^ 대한민국 국무회의 규정 제6조 제2항

- ^ 대한민국 국무회의 규정 제8조

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제4장 제2절 제2관 제89조

- ^ 대한민국 정부조직법 제2장 제15조, 제16조

- ^ 대한민국 정부조직법 제4장 행정각부

- ^ 대한민국 정부조직법 제3장 제22조

- ^ Established to consolidate most Saemangeum development projects and their support functions (currently provided by many different government bodies) into a single government agency for maximum efficiency. Commenced operation on September 12th, 2013.

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제4장 제2절 제4관 감사원

- ^ 대한민국 정부조직법 제2장 제17조

- ^ 대한민국 방송통신위원회의 설치 및 운영에 관한 법률 제2장 제3조

- ^ a b «National Human Rights Commission Of Korea Act». Korea Legislation Research Institute. Retrieved 2022-05-01.

- ^ «Kim, J. (2013). Constitutional Law. In: Introduction to Korean Law. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. pp. 52-54». doi:10.1007/978-3-642-31689-0_2. Retrieved 2022-05-01.

- ^ «2009Hun-Ra6, October 28, 2010» (in Korean). Retrieved 2022-05-01.

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제4장 제2절 제2관 제91조

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제4장 제2절 제2관 제92조

- ^ 대한민국 헌법 제4장 제2절 제2관 제93조

- ^ 대한민국 국가과학기술자문회의법 제1조

- ^ 대한민국 정부조직법 제3장 제22조의 2

- ^ 대한민국 정부조직법 제3장 제22조의 3

- ^ 대한민국 정부조직법 제3장 제23조

- ^ 대한민국 정부조직법 제3장 제25조

- ^ 대한민국 독점규제 및 공정거래에 관한 법률 제9장 제35조

- ^ 대한민국 부패방지 및 국민권익위원회의 설치와 운영에 관한 법률 제2장 제11조

- ^ 대한민국 금융위원회의 설치 등에 관한 법률 제2장 제1절 제3조

- ^ 개인정보 보호법 제2장 제7조

- ^ 대한민국 원자력안전위원회의 설치 및 운영에 관한 법률 제2장 제3조

- ^ a b c «Act On The Establishment And Operation Of The Corruption Investigation Office For High-ranking Officials». Korea Legislation Research Institute. Retrieved 2022-05-01.

- ^ «2020Hun-Ma264, January 28, 2021» (in Korean). Retrieved 2022-05-01.

- ^ «안전행정부 정부청사관리소». Archived from the original on 2013-05-31. Retrieved 2013-03-25.

- ^ «국토교통부 행정중심복합도시건설청». Archived from the original on 2007-09-12. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ^ Representation System(Elected Person) Archived 2008-04-22 at the Wayback Machine, the NEC, Retrieved on April 10, 2008

Further reading[edit]

- Korea Overseas Information Service (2003). Handbook of Korea, 11th ed. Seoul: Hollym. ISBN 978-1-56591-212-0.

- Kim, Jongcheol (2012). Constitutional Law. In: Introduction to Korean Law. Berlin, Heidelberg.: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-31689-0_2. ISBN 978-3-642-31689-0.

External links[edit]

- Official website

Слова президента Южной Кореи об оружии для Украины вызвали критику Москвы

Почему один из основных союзников США не спешит предоставлять военную помощь Киеву

Сеул до сих пор не поставлял на Украину оружие из-за возможной реакции России

В Москве резко отреагировали на слова президента Южной Кореи Юн Сок Ёля о возможности поставки вооружений на Украину. Какую позицию сейчас занимает Сеул, разбирался РБК

Гаубица K9 и танк K2

Почему президент Южной Кореи заговорил об оружии

Южная Корея может начать поставлять на Украину оружие в случае возникновения серьезной угрозы мирному населению этой страны, заявил южнокорейский президент Юн Сок Ёль в интервью агентству Reuters, вышедшем 19 апреля. «Если возникнет ситуация, с которой международное сообщество не сможет мириться, например в случае масштабных нападений на мирное население <…> или серьезных нарушений законов войны, то нам будет сложно настаивать лишь на гуманитарной или финансовой помощи», — сказал он.

Агентство отмечает, что президент Республики Корея впервые заговорил о возможной передаче вооружений Киеву. По мнению Юн Сок Ёля, международное право не ограничивает степень поддержки обороны и восстановления Украины. Южнокорейские власти примут «наиболее подходящие меры» с учетом развития ситуации в зоне боевых действий и отношений с конфликтующими сторонами, сказал он. При этом президент последовательно осуждает военные действия в регионе, он назвал их «незаконными и нелегитимными».

Интервью вышло в преддверии визита Юна в Вашингтон, запланированного на следующую неделю. Там у него должны пройти переговоры с президентом США Джо Байденом, приуроченные к 70-летию установления союзнических связей между двумя странами.

США выступают за расширение военной поддержки Украине. Неделей раньше стало известно, что США подписали контракт с правительством Южной Кореи на получение 500 тыс. 155-миллиметровых снарядов в долг. Об этом сообщила южнокорейская газета Dong-a Ilbo со ссылкой на источники в правительстве. По данным газеты, это в пять раз больше количества боеприпасов, которые Сеул передал Америке в 2022 году (100 тыс.), и примерно половина от того объема, который США поставили Украине в том же году. По условиям сделки между Вашингтоном и Сеулом, снаряды должны остаться на территории США, однако их предоставление увеличит возможности оказания военной помощи Украине.

Что удерживает Сеул от поставок

С начала российской специальной военной операции Южная Корея передавала Украине товары медицинского назначения и нелетальное военное оборудование, такое как противогазы.

Причин для отказа от поставок оружия у Сеула несколько. Первая — внутренняя. Согласно действующему Закону о внешней торговле, правительству запрещен экспорт вооружений за исключением «мирных целей», то есть для поддержания мира. Как уточняет Economist, Сеул не всегда буквально следовал этому закону, в частности продавал оружие Саудовской Аравии и ОАЭ, которые потом отправляли его участникам гражданской войны в Йемене. Такие же ограничения действовали в Норвегии, Германии и Швеции, но они были пересмотрены с начала масштабных военных действий на Украине, напомнил во время своего визита в Южную Корею в январе генеральный секретарь НАТО Йенс Столтенберг.

Сеулу тоже, чтобы изменить эту политику, придется менять законодательство. При этом парламент контролирует оппозиционная президенту демократическая партия «Тобуро». Позиция ее лидера Ли Чжэ Мёна достаточно противоречива. Сперва он говорил, что президент Украины Владимир Зеленский тоже несет ответственность за начало военных действий. Но, как отмечает Economist, более чем за год конфликта Ли скорректировал свои взгляды, но это не гарантирует того, что «Тобуро» поддержит изменение Закона о внешней торговле. Проведенный в июне прошлого года опрос Gallup Korea показал, что только 15% респондентов в стране поддерживают предоставление летального оружия Киеву.

Вторая причина опасений Сеула — возможный ответ России. В среду его сформулировал заместитель председателя Совета безопасности России Дмитрий Медведев: «Интересно, что скажут жители этой страны (Южной Кореи. — РБК), когда увидят новейшие образцы российского оружия у своих ближайших соседей — наших партнеров из КНДР?»

Экспорт и импорт вооружений из Северной Кореи был значительно ограничен решением Совета Безопасности ООН в 2006 году, а в 2009 и 2016 годах при поддержке России режим был ужесточен практически до полного эмбарго.

Прежняя администрация Южной Кореи (Юн вступил в должность президента в мае прошлого года) не хотела портить отношения с Россией, которую рассматривала как потенциального партнера в возобновлении переговоров по ядерной программе Северной Кореи, а нынешняя опасается, что Россия может ответить предоставлением КНДР современных авиационных и других технологий, которые позволят Пхеньяну продвинуть вперед свою программу вооружений, указал в издании The Diplomat Трой Стангарон из американского Института экономики Кореи.

Северная Корея, которая до сих пор формально находится с Южной в состоянии войны (перемирие было заключено в 1953 году), в последнее время нарастила темп ракетных испытаний. В частности, ею в 2022 году были осуществлены 68 пусков ракет — в десять раз больше, чем годом ранее, в нынешнем году — уже 12 запусков, подсчитал журнал Time. Последними стали прошедшие 13 апреля испытания новой баллистической ракеты большой дальности.

Рост военной промышленности Южной Кореи

По данным газеты The New York Times, в 2022 году Южная Корея экспортировала оружия на $17,3 млрд. Большая часть этого объема пришлась на Польшу, которая в рамках модернизации своих вооруженных сил заключила с Сеулом контракты на поставку танков K2, гаубиц K9 и других видов вооружений на сумму $12,4 млрд.

Согласно данным Стокгольмского института исследования проблем мира (SIPRI), среди крупнейших 25 стран — экспортеров оружия Южная Корея в период с 2017 по 2021 год наращивала свои возможности быстрее других и в итоге вышла на восьмое место с долей мирового рынка 2,8%.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| President of the Republic of Korea | |

|---|---|

| 대한민국 대통령 | |

Seal of the President |

|

Standard of the President |

|

|

Incumbent |

|

| Executive branch of the Government of South Korea Office of the President |

|

| Style |

|

| Type |

|

| Member of |

|

| Residence | Presidential residence |

| Seat | Seoul |

| Appointer | Direct popular vote |

| Term length | Five years, non-renewable |

| Constituting instrument | Constitution of South Korea |

| Precursor | President of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea |

| Formation | 24 July 1948; 74 years ago |

| First holder | Syngman Rhee |

| Unofficial names | President of South Korea |

| Deputy | Prime Minister of South Korea |

| Salary | ₩240,648,000 annually (2021)[1] |

| Website | Official website (in English) Official website (in Korean) |

The president of the Republic of Korea (Korean: 대한민국 대통령; RR: Daehanmin-guk daetongnyeong), also known as the president of South Korea (Korean: 대통령), is the head of state and head of government of the Republic of Korea. The president leads the State Council, and is the chief of the executive branch of the national government as well as the commander-in-chief of the Republic of Korea Armed Forces.

The Constitution and the amended Presidential Election Act of 1987 provide for election of the president by direct, secret ballot, ending sixteen years of indirect presidential elections under the preceding two authoritarian governments. The president is directly elected to a five-year term, with no possibility of re-election.[2] If a presidential vacancy should occur, a successor must be elected within sixty days, during which time presidential duties are to be performed by the prime minister or other senior cabinet members in the order of priority as determined by law. The president is exempt from criminal liability (except for insurrection or treason).

The current president, Yoon Suk-yeol, a former prosecutor general and member of the conservative People Power Party, assumed office on 10 May 2022,[3][4] after defeating the Democratic Party’s nominee Lee Jae-myung with a narrow 48.5% plurality in the 2022 South Korean presidential election.[5]

History[edit]

Prior to the establishment of the First Republic in 1948, the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea established in Shanghai in September 1919 as the continuation of several governments proclaimed in the aftermath of March 1st Movement earlier that year coordinated Korean people’s resistance against the Japanese occupation. The legitimacy of the Provisional Government has been recognized and succeeded by South Korea in the latter’s original Constitution of 1948 and the current Constitution of 1988.

The presidential term has been set at five years since 1988. It was previously set at four years from 1948 to 1972, six years from 1972 to 1981, and seven years from 1981 to 1988. Since 1981, the president has been barred from re-election.

Powers and duties of the president[edit]

Chapter 3 of the South Korean constitution states the duties and the powers of the president.

The president is required to:

- uphold the Constitution

- preserve the safety and homeland of South Korea

- work for the peaceful reunification of Korea, typically act as the Chairperson of the Peaceful Unification Advisory Council

Also, the president is given the powers:

- as the head of the executive branch of government

- as the commander-in-chief of the South Korean military

- to declare war

- to hold referendums regarding issues of national importance

- to issue executive orders

- to issue medals in honor of service for the nation

- to issue pardons

- to declare a state of emergency suspending all laws or enacting a state of martial law

- to veto bills (subject to a two thirds majority veto override by the National Assembly)[6]

If the National Assembly votes against a presidential decision, it will be declared void immediately.